Could the Internet Ever Be Destroyed?

The raging battle over SOPA and PIPA, the proposed anti-piracy laws, is looking more and more likely to end in favor of Internet freedom — but it won't be the last battle of its kind. Although, ethereal as it is, the Internet seems destined to survive in some form or another, experts warn that there are many threats to its status quo existence, and there is much about it that could be ruined or lost.

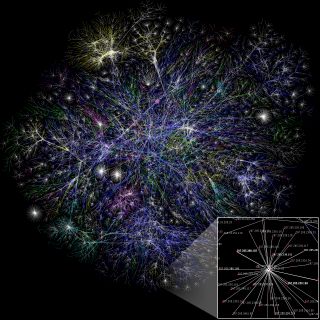

Physical destruction

A vast behemoth that can route around outages and self-heal, the Internet has grown physically invulnerable to destruction by bombs, fires or natural disasters — within countries, at least. It's "very richly interconnected," said David Clark, a computer scientist at MIT who was a leader in the development of the Internet during the 1970s. "You would have to work real hard to find a small number of places where you could seriously disrupt connectivity." On 9/11, for example, the destruction of the major switching center in south Manhattan disrupted service locally. But service was restored about 15 minutes later when the center "healed" as the built-in protocols routed users and information around the outage.

However, while it's essentially impossible to cripple connectivity internally in a country, Clark said it is conceivable that one country could block another's access to its share of the Internet cloud; this could be done by severing the actual cables that carry Internet data between the two countries. Thousands of miles of undersea fiber-optic cables that convey data from continent to continent rise out of the ocean in only a few dozen locations, branching out from those hubs to connect to millions of computers. But if someone were to blow up one of these hubs — the station in Miami, for example, which handles some 90 percent of the Internet traffic between North America and Latin America — the Internet connection between the two would be severely hampered until the infrastructure was repaired.

Such a move would be "an act of cyberwar," Clark told Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience.

Content cache

Even an extreme disruption of international connectivity would not seriously threaten the survival of Web content itself. A "hard" copy of most data is stored in nonvolatile memory, which sticks around with or without power, and whether you have Internet access to it or not. Furthermore, according to William Lehr, an MIT economist who studies the economics and regulatory policy of the Internet-infrastructure industries, the corporate data centers that harbor Web content — everything from your emails to this article — have sophisticated ways to back up and diversely store the data, including simply storing copies in multiple locations.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Google even stores cached copies of all Wikipedia pages; these were accessible on Jan. 18 when Wikipedia took its own versions of the pages offline in protest of SOPA and PIPA.

This diversified storage plan keeps the content itself safe, but it also offers some protection against loss of access to any one copy of the data in the event of a cyberwar. For example, if power were cut to a server, you may be unable to reach a website on its home server, but you mayfind a cached version of the content stored on another, accessible server. Or, "If you wanted data that was not available from a server in country X, you may be able to get substantively the same data from a server in country Y," Lehr said.

Internet arms race

The redundancy of so much online content and of connectivity routes makes the Internet resilient to physical attacks, but a much more serious threat to its status quo existence is government regulation or censorship. In the early days of Egypt's Arab Spring uprising, the government of Hosni Mubarak attempted to shut down the country's Internet in order to cripple protesters' ability to organize; it did this by ordering the state-controlled Internet Service Provider (ISP), which grants Internet access to customers, to cut service.

"ISPs have direct control of the Internet, so what happens in any country depends on the control that the state has over those ISPs," Clark said at the time. "Some countries regulate the ISPs much more heavily. China has in the past 'turned off' the Internet in various regions."

However, in Egypt last year, many protesters found ways to bootstrap connectivity and bypass the shut-off, such as by using smartphones to communicate with the global Internet over cellular networks and tapping into private companies' Intranet connections. "[A] lot of the connectivity to protesters was provided by workers who made access available to their business networks," Lehr said.

If, in future, the U.S. government sought to shut down or limit Internet access, similar workarounds would crop up, and they would grow more sophisticated as the regulatory methods became more extreme — a "weapons race," Lehr called it. "The tools for fighting the war are mostly defensive (fire walls, shutting down interconnects, monitoring, locking up folks who have violated 'laws') but also can be offensive (viruses to attack hostile websites/destroy content, locking folks up preemptively, etc.)."

Governments could also simply tax Internet access, or providers could jack up the prices, in such a way as to price it out of reach of most people.

Lehr added that, while no single government could destroy the Internet everywhere, it could certainly cripple it sufficiently to render its use unattractive for people within its country of governance.

In the balance

Bad regulation, be it in any particular country or on the international scale, could severely hamper the Internet's value and its ability to grow, Lehr said. While some version of the Internet is likely to exist as long as humanity does, what might be lost or greatly diminished is "the openness of the Internet."

This openness is useful both economically and socially, but it is also a source of problems, Lehr noted; it lends itself to endless security and privacy attacks, junk mail, viruses, malware and so on. He believes new security models must be developed to protect privacy and security while still allowing the Internet to function.

"Whether we can effectively strike that balance is a difficult challenge and work in progress."

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Most Popular