Earliest Pregnant Reptile Pushes Back Fossil Record of Live Birth

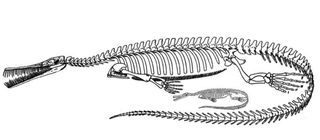

Newly found fossils of embryos from the first aquatic reptiles called mesosaurs — along with a pregnant female — may be the oldest known example of birth given to live young instead of eggs, scientists report.

Both mammals and reptiles wrap their developing embryos in protective layers, something that helped the little ones survive and ultimately helped their ancestors conquer the land. Mammals often keep these membrane-swaddled offspring within them, giving birth to live young, while reptiles typically lay their membrane-bundled progeny in eggs.

However, there are some oddballs: Some mammals, such as the platypus, lay eggs, while some reptiles, such as most vipers, are viviparous, giving birth to live young.

The fact that mammals and reptiles surround their embryos with these protective layers makes them known as amniotes. The fossil record of amniotic eggs and embryos is very sparse, and as such, scientists have little information about when, how and why they evolved.

Now researchers have uncovered two exceptionally well-preserved 280-million-year-old fossils that are the earliest amniotic embryos found yet. These belonged to mesosaurs, the first aquatic reptiles and what may be the most primitive known reptiles. [T. Rex of the Seas: A Mesosaur Gallery]

The two fossil embryos, unearthed in Uruguay and Brazil, are about a quarter-inch to a half-inch long (0.75 to 1.5 centimeters). The gypsum crystals in the rocks they were found in suggest the reptiles lived in salty, oxygen-poor water, which helped preserve these embryos until discovery. The mesosaurs apparently once dwelled alongside burrowing worms and now-extinct crustaceans.

"Despite their age and their delicate nature, they remained in the rocks all that long time almost perfectly preserved," said researcher Graciela Piñeiro, a paleontologist at the University of the Republic in Uruguay.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Intriguingly, the embryos lacked recognizable eggshells. Moreover, one well-developed embryo was found within an adult presumed to be a pregnant female, suggesting that mesosaurs were viviparous.

One of the well-developed mesosaur embryos was discovered on its own, not inside an adult. This might suggest the mesosaurs laid eggs after embryos reached advanced stages of development. On the other hand, this specimen could represent a miscarried embryo.

"With the discovery of the mesosaur embryos, we may now have direct evidences that embryo retention or viviparity were strategies developed by early amniotes," Piñeiro told LiveScience.

Other extinct aquatic reptiles were known to give birth to live young, including the plesiosaur; in 2011, scientists reported a pregnant plesiosaur, a marine reptile, which lived some 78 million years ago.

These new findings push back the known records of live birth and amniotic embryos by 60 million and 90 million years, respectively.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 7 in the journal Historical Biology.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.