On December 6, 2011, a hacker using the handle "sup_g" private-messaged Hector Xavier Monsegur, otherwise known as "Sabu," on Anonymous's IRC server to tell him of a server he had gained access to. But "sup_g"—alleged by the government to be Jeremy Hammond—didn't know that the whole conversation was being logged by the FBI, and that Monsegur had turned confidential informant. "Yo, you round? working on this new target."

The target was the server of Stratfor, the Austin-based global intelligence company that would soon become synonymous with the hacker phrase, "pwned." Over the course of the Anonymous cell Antisec's hacking and exploiting of the company's IT infrastructure, the group of hackers would expose credit card and other personal information of over 60,000 Stratfor customers and a vast archive of e-mail correspondence between the company's employees and customers in the private and government sectors. And it all started with a control panel hack.

According to the FBI, Hammond, also more widely known by the handle "Anarchaos," sent Monsegur a link on a TOR network hidden server to a screenshot of Stratfor's administrative panel for its website. Antisec has used panel hacks to exploit a number of other sites, including the Federal Trade Commission's sites hosted on Media Temple.

Using SQL injection exploits against interfaces to the Web administration application, hackers have been able to gain low-level control over sites and do with them what they will. But in the process of exploiting the control panel, Hammond found there was potential for more than just a simple Web defacement in the Stratfor site. "This site is a paid membership where they gain access to articles," he messaged Monsegur . "It stores billing as well - cards. It's encrypted though. I think I can reverse it though but the encryption keys are store[d] on their server (which we can use mysql to read)."

Hammond said that once he found the keys, he could write a script to export the data "en mass[e]."

As it turns out, the credit card numbers were not encrypted, but stored in plaintext in Stratfor's MySQL database. So once Hammond gained access to the database, he and others were able to export all of the data. Next, he turned to the e-mail system and other server applications running Stratfor's intranet—all of which ran within the same hosting service at Austin-based Core NAP.

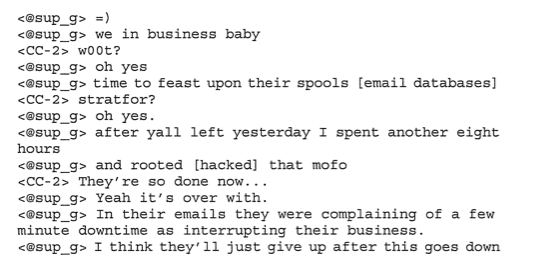

By December 14, according to the FBI's investigation, Hammond had managed to "root" Stratfor's mail server as well. In a chat on an IRC channel named #lulzxmas, he told another Anonymous member, "we in business baby time to feast upon their spools."

He noted that in their e-mails, employees at Stratfor had been complaining about downtime—possibly caused by Hammond gaining control of the server. Hammond and others not named in the indictment discussed options for offloading the data for viewing on hidden TOR sites, including using stolen credit card information to secure servers. Hammond decided to put off using credit card data until after the end of December—so that the charges wouldn't hit their owners' statements until the end of January.

At the instruction of the FBI, Monsegur offered Hammond a server to store the data being extracted from Stratfor. Hammond agreed, and told others that they would use Monsegur's server as a "first base of operations" before moving it elsewhere.

On December 24, the group showed its hand somewhat with the defacement of Stratfor's site, the deleting of the contents of four servers, and posting of 30,000 of the credit card numbers that had been stolen from the site's database—plus evidence of "donations" made with some of them to charities such as the Red Cross.

But some of the card numbers were held in reserve, and the hacking wasn't done. Again in IRC, on December 26, Hammond told another Antisec member that he had logged into Stratfor's Clearspace collaboration server, and had found reports for the New York Police Department's SHIELD counterterrorism partnership program.

At the same time, he reported that he and others in the group had isolated 50,000 accounts of site users with military and government e-mail addresses, and had cracked the hash of the passwords for 4,500 of them, in hopes of using them for other efforts. By January 11, the group working with Hammond had started to unpack the contents of the Stratfor servers onto the server provided by Monesgur—providing a treasure trove of evidence for the FBI.

Getting nailed

The FBI tracked down Hammond with information he had shared in IRC logs from different aliases, and by tying those aliases together with the help of Monsegur. Hammond gave away his location by revealing last August that friends of his had been arrested at the "Midwest Rising" protest in St. Louis on August 15. In another chat, he revealed that he had been arrested in New York City in 2004 during the Republican National Convention. And he also revealed information that indicated he had served time in a federal prison.

Using federal criminal records and other data, FBI investigators were able to narrow the field of suspects rapidly. The FBI had dealt with Hammond before—he had been arrested in March of 2005 for hacking into the site of Protest Warrior, a conservative political activist group, and stealing its database, including credit card information. He served two years in federal prison, followed by three years of supervised release.

Listing image by Photograph by chris riebschlager

reader comments

35