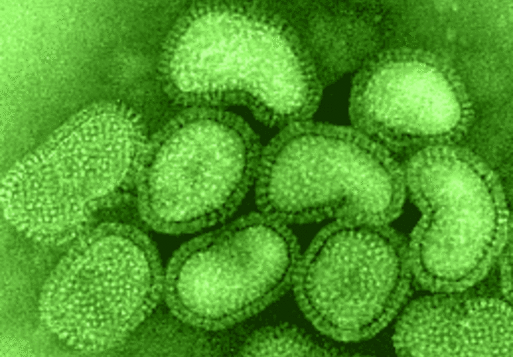

The 2009 flu pandemic, although not especially deadly, revealed just how quickly a new influenza virus could elude surveillance and spread internationally. It also left health experts eying the disease that many fear could cause the next pandemic: H5N1, the avian flu. According to World Health Organization standards, that virus is phenomenally deadly, killing about half the people that contract it. So far, however, almost all the known cases came from people who were in direct contact with poultry; the flu doesn't seem to spread among mammals.

The great unanswered question was whether we could continue to rely on H5N1's limited transmission. Recently, some researchers set out to answer that question, and came up with a disturbing answer: it was relatively easy to evolve a form of H5N1 that spread in ferrets, another mammalian species, without it losing any of its virulence. Two labs identified the exact mutations that enabled this new host range, and were preparing to publish their results in Science and/or Nature. At that point, the US government's National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) responded by requesting that the journals delay publication and limit the content released. That, in turn, prompted the viral research community to put a two-month hold on further research.

That's where things stood on February 2, when the New York Academy of Sciences hosted a panel discussion on H5N1 and other dual-use research (research that has both public benefit and weapons applications). The panel included two members of the NSABB, representatives from both Science and Nature, a number of virus researchers, a public health expert, and a member of the Defense Department, and they spent two hours in a lively and sometimes contentious discussion of how to handle our current situation.

What's the consensus on the threat?

Most scientists disagree with you—we have no choice but to act as if you are wrong

We now clearly know that H5N1 can spread among mammals. What does that tell us about the human risk? That obvious question triggered the most contentious arguments of the evening. One of the panelists, Mount Sinai's Peter Palese, has recently published a paper in which he argued that fears of H5N1 are overblown. In both the paper and at the discussion, he argued that the WHO only counted cases that resulted in hospitalization, and some studies had found a low but significant level of people who carried H5N1 but remained asymptomatic. And, while he was at it, he questioned whether ferrets were a valuable model for the human response. Overall, it was clear that he didn't think the research should be causing much fuss at all.

But, in stating that, he managed to create quite a bit of fuss. The two members of the NSABB on the panel, Einstein's Arturo Casadevall and Minnesota's Michael Osterholm, noted that their group's responsibility in evaluating the H5N1 research was to identify the best opinion of the experts in the field. And, as far as they could tell, Palese's opinion was way outside of the expert consensus—most experts found the work a cause for great concern. Osterholm had actually prepared a point-by-point rebuttal of Palese's publication, focusing on the technical weaknesses of the various studies he used to support his argument.

Both Osterholm and Casadevall pointed out that, even if the WHO's estimates of the virus' lethality were high by a factor of 10, it would still be far more deadly than the 1918 flu. If it were off by 100, it could still cause 200 million deaths. At one point, turning to Palese, Osterholm said, bluntly, "most scientists disagree with you—we have no choice but to act as if you are wrong."

But Casadevall had what might have been the most compelling take on matters. When the NSABB was called on to look into the H5N1 work, he said, he went into it with the feeling that it was important scientific research and needed to be shared widely with the community. After talking with enough influenza experts, though, "I changed my mind." By the end of his work on the matter, he agreed with the panel's recommendation that access to the results should be limited. The strength of the consensus among the experts had been enough to get him to rethink his initial reaction.

What to do when research makes the experts nervous

So, if the H5N1 research was enough to make flu experts nervous, what should a journal do with a paper that describes the research in detail? Both Nature and Science (represented by Véronique Kiermer and Barbara Jasny, respectively) are currently struggling with just that. Although the journals haven't officially announced how they'd handle things, they and others have mooted running a redacted form of the papers, with key experimental details and data removed from the text, and the entire panel seemed to be treating that option as if it was how the journals would proceed.

The panel was asked to estimate how many people had seen all the sensitive data, and estimates ranged from a few hundred to about 1,000. To some extent, the whole debate about this research is taking place after the fact.

That's a pretty radical decision. Science, in part, is based on the free exchange of information. What good is a publication with key pieces of information cut out?

Kiermer said that the paper will serve three functions, even in its limited form. The first is that the message of the paper is important. It's no longer safe to assume that, since the avian flu hasn't spread among humans to this point, that it never will. And that has some major implications for global public health; at various points members of the panel described our international monitoring systems as limited and poorly organized.

Practically, even a redacted publication in a major journal would allow the researchers to gain credit for their work, which can be valuable in terms of securing funding or promotion within their institutions. Finally, Kiermer said that the publications will alert those who have a need for the details and will treat them responsibly, allowing them to request an unredacted version of the paper. Both Science and Nature are currently exploring ways to identify those people that deserve access to the full paper.

But both Kiermer and Jasny were clearly unhappy with being thrust into the role of gatekeepers; Jasny referred to it as being told to "find a solution to a mess that is not of our making," and stated "I hope that it's a one-time event."

Even with the paper being held up, however, lots of people know key details. Both journals sent versions out to reviewers and distributed copies among their editorial staff; the entire NSABB got copies, and distributed some to experts they consulted with; the results came to public attention because they were presented at a meeting. The panel was asked to estimate how many people had seen all the sensitive data, and estimates ranged from a few hundred to about 1,000.

To some extent, the whole debate about this research is taking place after the fact.

"We don't want to be surprised again"

How do we get to the point where we no longer hold up papers after they're written and put research on hiatus only after the most significant work has been done? The panel appeared unanimous in hoping that some general lessons could be drawn from this mess, but were a bit less unanimous in deciding what those lessons were.

Poor people all over the world are killing their chickens for you to contain the avian flu. They are going bankrupt for you.

The H5N1 work is a clear example of what's called dual-use research, since it's not difficult to imagine the threat potential of a lethal flu virus. But the panel generally agreed that all research is dual-use. Very basic biology and chemistry research, done decades earlier, was essential to giving us the ability to synthesize arbitrary DNA sequences and link them together; that ability now makes the publication of the DNA sequence that encodes newly evolved H5N1 virus a threat, since anyone can order up the requisite DNA to make a copy.

That fact also makes Osterholm's preferred form of evaluation, a risk-benefit analysis, rather tricky. How can we possibly identify benefits of research that will completely revolutionize their field, especially when those benefits only arise decades later? (As virologist Vincent Racinoello pointed out, work on restriction enzymes was considered a backwater in the 1970s; now, the entire biotech industry relies on them.)

The key, according to Casadevall, is identifying what's been called dual-use research of concern, or DURC. The panel generally agreed that most people could see the difference between enabling research, like the development of DNA synthesis techniques, and research that creates an actual risk, like the resurrection of the 1918 flu virus (which was the first time the NSABB was called into action).

That seems like a good idea, but doesn't solve the basic problem: who identifies this research, and how do they respond to it? Even within the US, which has a highly developed biomedical research system, there's no formal body that handles issues like this, and it's not clear if anybody has the appetite to create one. Researchers will be leery of any additional oversight—Casadevall quipped that he already has to write 100 page descriptions justifying his use of lab mice at the same time he could walk to a hardware store and buy a 100 different products meant to brutally kill them. And the US public has little appetite for additional regulatory schemes, or the costs and bureaucracy needed to ensure they're effective.

And that's just within the US. Any work of this sort has clear international implications, which play out on multiple levels. Many other nations support labs that operate at biosafety levels 3 and 4, which are meant to handle DURC, but the training, inspection, and maintenance of these facilities varies widely.

Many other nations that don't support a biomedical research community are on the front lines of the efforts to contain avian flu. As Laurie Garrett from the Council on Foreign Relations put it, we need them to buy in to whatever we do. "Poor people all over the world are killing their chickens for you" to contain the avian flu, Garrett said. "They are going bankrupt for you." One consequence of that is that nations like Indonesia have been calling for full and unfettered access to the H5N1 work, since it will allow them to improve their surveillance system.

So, if there was general agreement that we need to do better at handling dual-use research, there was quite a bit less consensus on how to go about that.

Listing image by Photograph by ucla.edu

reader comments

34