A huge hunk of Russian space junk is set to crash to Earth in the next few days, but nobody knows exactly when or where it's going to come down.

The 14.5-ton Mars probe Phobos-Grunt, which got stuck in Earth orbit shortly after its Nov. 8 launch, may re-enter the atmosphere at 11:22 a.m. EST (1622 GMT) on Sunday (Jan. 15), according to the latest estimate published today (Jan. 13) by Roscosmos, Russia's space agency.

If that projection is accurate, pieces of the failed spacecraft will splash into the Atlantic Ocean about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) south of Buenos Aires.

But that's a big if.

Uncertain predictions

The predicted time and place of re-entry could change in the future, Roscosmos said. Indeed, the newest estimate is substantially different from two others the space agency issued earlier in the week, which had the probe coming down earlier on Sunday and falling into the Indian Ocean off the coast of Java or near Madagascar. [Photos of the Phobos-Grunt mission]

Further, other organizations and observers tracking Phobos-Grunt have their own estimates, some of which roughly agree with Roscosmos' predictions and some of which have the probe crashing later, perhaps early Monday morning (Jan. 16).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

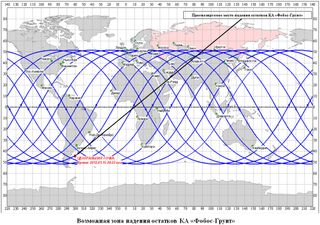

So all we know for certain right now is that Phobos-Grunt will fall to Earth soon, somewhere between 51.4 degrees north latitude and 51.4 degrees south latitude — a stretch of the planet ranging from London in the north to the Falkland Islands in the south.

And the predictions won't really start firming up until shortly before the probe's fall, experts say.

"About two hours out, the U.S. military will publish their last re-entry prediction, and that will likely be the most accurate public prediction, as they have very accurate data on the object's orbit that will not be available publicly," said Brian Weeden, a technical adviser with the Secure World Foundation and a former orbital analyst with the Air Force.

"Up until then, I would take any prediction with a large grain of salt," Weeden told SPACE.com in an email.

Most of probe should burn up

Most of Phobos-Grunt's weight consists of toxic fuel, prompting some concern that its crash could spread dangerous chemicals over populated or environmentally sensitive areas. But Roscosmos officials have said that the fuel will burn up high in Earth's atmosphere.

The vast majority of Phobos-Grunt should meet the same fate, according to Roscosmos. The space agency estimates that no more than 20 to 30 pieces of the probe, weighing a total of less than 440 pounds (200 kilograms), will reach the ground.

While it's tough to vet these claims, they're likely to be fairly accurate, Weeden said.

"Since they have the most data on its construction and design, I don’t think anyone else is in a position at this point to contradict them," he said. "And their statement is reasonable and consistent with what normally happens."

At this point, the world may be getting rather accustomed to giant pieces of metal falling from the sky. Phobos-Grunt's crash will be the third uncontrolled re-entry of a big spacecraft in the last four months, following NASA's defunct UARS satellite in September and the dead German ROSAT satellite in October.

Nobody on the ground was hurt by UARS or ROSAT debris. In fact, no one is known to have ever been injured by a chunk of man-made space junk.

The $165 million Phobos-Grunt spacecraft launched Nov. 8 on a mission to collect soil samples from the Mars moon Phobos and send them back to Earth ("grunt" means "soil" in Russian). Shortly after liftoff, however, the probe's engines failed to fire as planned to send it on a path toward the Red Planet.

Russian officials still aren't sure what caused the failure, though they recently raised the possibility that some sort of sabotage may be responsible.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Most Popular