Female Explorer Gets Her Due, 2 Centuries Later

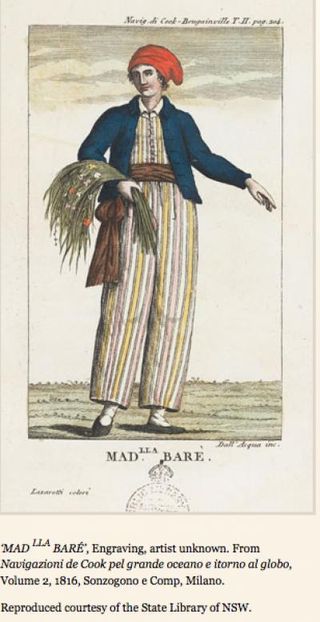

More than two centuries after she disguised herself as a man and set out on a journey that would make her the first woman to circle the globe, pioneering botanist Jeanne Baret is getting some long-deserved recognition.

A newly described plant species has been christened Solanum baretiae in her honor. Biologist Eric Tepe, with the University of Utah and the University of Cincinnati, named the newfound species after hearing about Baret's unsung work during a National Public Radio interview with Glynis Ridley, author of the biography, "The Discovery of Jeanne Baret" (Crown, 2010), on the program "All Things Considered."

Baret collected thousands of plant specimens from exotic locales around the globe, and, according to Ridley, likely collected the first specimen of one of the world's most beloved flowering plants — bougainvillea.

No women allowed

Baret's journey began in 1766, on the first French naval expedition charged with circumnavigating the planet. The voyage was to take three years, yet Baret would not return to France until nearly a decade later. The female explorer's extraordinary travels and detour into cross-dressing were simply an extension of an already extraordinary life.

A woman of humble origins, yet an accomplished expert on France's native plants, Baret was the live-in companion of Philibert Commerson, a renowned botanist who was tapped to lead scientific work on the expedition. Commerson was allowed to bring an assistant, but it could not be Baret. Women were forbidden from traveling aboard French naval vessels.

"We of course don't have the recorded conversation between them, but I suggest in the book that what started as a bit of a joke — 'It's a shame you're not a man, then you could come with me' — acquired some momentum," Ridley told OurAmazingPlanet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fast forward to the day of departure, and Baret presented herself at the dock, dressed as a teenage boy, and offered her services as an assistant to Commerson, who, quite conveniently, claimed he'd been unable to find one.

Once on board, the pair were given the captain's cabin — they had a great deal of scientific equipment. "If that hadn't happened, I think the game would have been up almost immediately," Ridley said.

Yet before long, she said, the crew began to suspect Baret was not what she seemed. The ship was only 100 feet (30 meters) long and 30 feet (9 m) wide, and "the captain of the ship actually interrogated her at one point," Ridley said, "and she said she was a eunuch." The only way to verify her claim would have been embarrassing for everyone, and for at least two years, Baret conducted her scientific work with relatively little hassle.

Yet when the voyage reached the island of Mauritius, off the southeast coast of Africa, the captain unceremoniously booted the couple from the expedition. Commerson died there in 1773, and, because they were not married, Baret was left with nothing. She married a marine and in 1775 returned with him to France, where she died in relative obscurity in 1807.

More than 70 plant species found by the couple have been named for Commerson. The flowering vine bouganvillea was named for the voyage's commanding officer, Louis Antoine de Bougainville. Now, Baret is getting a taxonomic salute of her own.

Remembered, at last

Tepe discovered Solanum baretiae, a distant relative of the tomato and potato, while going through museum specimens collected several decades earlier.

"The discovery wasn't an Indiana Jones-type discovery, but, like most science, was much more subdued," Tepe wrote in an email. However, even though he was hunched over a microscope, he said the discovery was nevertheless a eureka moment. "Discoveries like these are always thrilling, even if not so adventuresome," he said.

Soon after, Tepe traveled to Peru, and tracked down his new species — a plant with dainty flowers that range from delicate purple to yellow to white, and leaves that come in an unusual range of shapes.

In 2010, with most of the hard work done, Tepe still lacked one thing — a name for his new species. That's when he heard Ridley's interview on the radio.

"I have always admired explorers, especially botanical explorers," he said. "We know many of their names, and they all have endured hardships in pursuit of interesting plants, but few have sacrificed so much and endured so much as Baret."

Yet it was one particular story that decided Tepe's choice. Ridley said that Commerson himself intended to name a genus of Madagascar plants with a showy range of leaves — a good representation, he thought, of Baret's many facets — for his partner, but died before he could publish.

"My new species also has highly variable leaves," Tepe said. He got in touch with Ridley, who loved the idea, "and here we are about a year later with the published name in hand," he said.

Ridley said that it must have been galling to watch all the important men on the expedition have things named in their honor, but Baret probably didn't expect such things for herself.

"I don't think she ever expected recognition in her own lifetime, just because women who were involved in science were thought of, at best, as something of an oddity, and, at worst, they were thought of as an abomination," Ridley said.

Although it's impossible to know, she said, Baret would probably be pleased to serve as scientific inspiration so many years later.

"I would say she would be very happy having something named after her," Ridley said. "And the fact that it's a plant that has some similarities to the plants that Commerson wanted to name after her is particularly cool."

- Hold Your Nose: 7 Foul Flowers

- Naughty by Nature: The Most Disgusting and Deadly Flowers

- Image Gallery: Plants in Danger

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.