Toxic Turnaround With Manganese

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Shiga toxin is a protein produced by certain strains of Shigella and E. coli bacteria. Infections by bacterial strains that carry Shiga toxin can lead to dangerous complications, including severe bloody diarrhea, kidney failure, and even death. New research suggests that manganese, a metal and an essential nutrient, may prevent those outcomes.

Ordinarily, dangerous proteins taken up by the cell are routed via a cellular compartment called the endosome to the lysosome, where they're destroyed. Shiga toxin, however, escapes this path by leaving the endosome, hitchhiking on a cellular protein, and traveling to the endoplasmic reticulum (the cell's protein production machinery, and on to the cell’s watery interior). Once there, the toxin halts protein production and kills the cell.

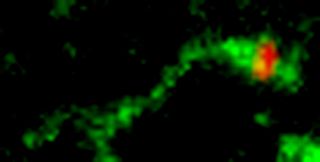

Pictured here, Shiga toxin (green) is sorted from the endosome into membrane tubules (red), which then pinch off and move to the Golgi apparatus.

Shiga toxin exploits a specific cellular protein called GPP130 found in the Golgi. According to new work by Carnegie Mellon University biologists Adam Linstedt and Somshuvra Mukhopadhyay, the toxin avoids destruction by binding to GPP130, essentially hitching a ride as the protein travels to the endosome and back again.

The researchers also discovered that manganese disrupts that movement and causes cells to destroy GPP130. They went on to find that tissue cultures and mice treated with manganese were protected from the toxin’s effects. More work needs to be done, but the results could point toward an inexpensive, life-saving treatment for millions of people worldwide infected by certain strains of Shigella and E. coli bacteria.

Manganese is just one example of the vital health role that metals play (read more about how metals play a key role in the body). For example, cobalt is found at the core of vitamin B12 and is key to making red blood cells, while iron allows those cells to ferry oxygen and other important chemicals to the body's tissues. Calcium not only strengthens bones but also plays a role in muscle, nerve function and blood clotting. Sodium and potassium help the heart and nerves communicate through electrical signals.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). To see more images and videos of basic biomedical research in action, visit NIH's Biomedical Beat Cool Image Gallery.

Editor's Note: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive.

Most Popular