Astronomers have discovered two potential alien planets that apparently survived being engulfed by their bloated, dying parent star.

The discovery is a surprise to many scientists, as it had been widely believed that no planet could withstand such a thorough and intense scorching, researchers say. Also a surprise: The hardy alien worlds seem to have inflicted their own damage on the expanded star, stripping it of much of its mass.

"To our knowledge, there has been no previous case reported where such a strong influence on the evolution of a star seems to have occurred," said study lead author Stephane Charpinet, of the University of Toulouse in France.

Studying a dying star's light

Charpinet and his colleagues made the find using NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope, which recently discovered the first two Earth-size worlds beyond our solar system.

For the new study, detailed in tomorrow's (Dec. 22) edition of the journal Nature, the researchers didn't set out looking for alien planets. Instead, they were studying a dying star called KIC 05807616. The star was once a "normal" main-sequence one like our own sun, but it's now several steps farther down the path of stellar evolution. [Vote! The Most Intriguing Alien Planets of 2011]

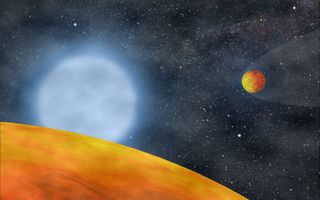

For instance, KIC 05807616 has already gone through its red-giant phase, bloating up dramatically after exhausting the stores of hydrogen fuel in its core. The star has since collapsed to a shrunken vestige of its former self, becoming what's known as a hot B subdwarf.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While studying KIC 05807616's light, Charpinet and his team noticed periodic brightness variations recurring every 5.8 and 8.2 hours. They determined that these variations were caused by two small planets zipping around the star in extremely close orbits.

Kepler normally detects planets by what's known as the "transit method," flagging the tiny brightness dips caused when a planet crosses in front of — or transits — a star's face, blocking some of its light.

But in this case, the researchers concluded that they weren't seeing dimming caused by planetary transits. Instead, Kepler was flagging light that the planets themselves were reflecting and emitting.

"Light that is directly emitted or reflected from extrasolar planets has been detected in the past, but this is the first time that this particular method has been used for the discovery of a planetary system," astronomer Eliza Kempton, of the University of California, Santa Cruz, wrote in an accompanying essay in the same issue of Nature.

The two newfound planet candidates, known as KOI 55.01 and KOI 55.02, still need to be confirmed by follow-up observations. Both appear to be slightly smaller than Earth, but they hug their host star much more closely than our planet does.

Both orbit at less than 1 per cent of the Earth-sun distance (which is about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers), researchers said, so both planets are almost certainly far too hot to support life as we know it.

Destroyed gas giants

The two potential exoplanets likely didn't start out so small and so close-in, researchers said. Before KIC 05807616 became a red giant, both alien worlds were probably Jupiter-like gas giants sitting farther away from the star.

But then KIC 05807616's stellar envelope bloated immensely, engulfing the two planets. This seems to have had serious consequences for both the star and the alien worlds, researchers said. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

"As the star puffs up and engulfs the planet, the planet has to plow through the star's hot atmosphere and that causes friction, sending it spiraling toward the star," study co-author Betsy Green, of the University of Arizona, said in a statement. "As it's doing that, it helps strip atmosphere off the star. At the same time, the friction with the star's envelope also strips the gaseous and liquid layers off the planet, leaving behind only some part of the solid core, scorched but still there."

These dramatic events could shed light on the evolution and ultimate fate of planetary systems, researchers said. Astronomers know of many systems with close-in giant planets, and some of them could eventually go down a similar road, leaving behind burnt-out planetary cores and a shrunken dwarf star.

Our own solar system will probably take a slightly different path, however. Our sun will become a red giant in about 5 billion years, likely expanding to engulf and thoroughly cook Mercury, Venus and Earth. But the sun will feel no reprisals, for these planets are too small to take a piece out of our star in the process, Charpinet said.

"It likely takes the engulfment of sufficiently massive giant planets comparable to Jupiter to influence the evolution of a star," Charpinet told SPACE.com in an email. "Our sun has giant planets, but they are probably too far away from it to be caught in the expanding star envelope during the red-giant phase."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.