Fossilized Skin Reveals Ancient Predator's Sharklike Moves

More than 80 million years ago, a giant reptile called a mosasaur likely glided gracefully through the water with the help of tiny scales covering its tough skin, and a powerful tail to boot, suggests the soft-tissue remains of one such aquatic beast.

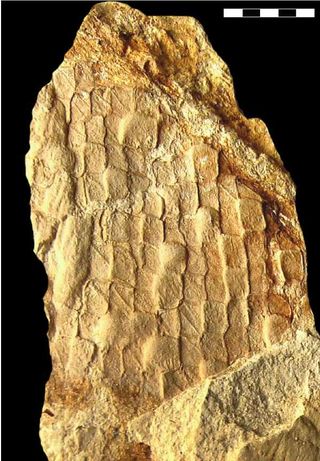

The fossilized pieces of mosasaur skin, discovered in Kansas in the 1950s but not analyzed thoroughly until now, give researchers a view of ancient lizard skin, inside and out. The marine animal's skin was pulled taut around the upper end of its body, which would have restricted its swimming motion to the lower half, they found.

"We previously had thought that they swam like snakes, that they used most of their body to make these undulating waves," study researcher Johan Lindgren, of Lund University in Sweden, told LiveScience "What we see is they are gradually pushing the part being used in swimming to the back." [T-Rex of the Seas: A Mosasaur Gallery]

Moving mosasaurs

Mosasaurs include a group of swimming reptiles thought to have evolved from an ancient relative of the monitor lizard, which left the land and returned to the sea during the early Cretaceous Period. Then more than 90 million years ago, mosasaurs quickly evolved to life in the water and soon became a top predator throughout the world's seas. They died out with the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago.

In the fossilized skin samples, the researchers can see not only the animal's scales, but also imprints of the protein fibers that made up its skin. They saw that these fibers often crisscrossed, suggesting that at least this front half of the mosasaur's body was stiff.

Rather than slithering through the water like today's water snakes, by moving their vertebrae from side to side, this tough, taut skin indicates that the mosasaur used its tail to propel itself forward. As such, the animal would've moved more like modern sharks and whales than snakes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They [the mosasaurs] have, for 200 years, been reconstructed as these serpentine creatures," Lindgren said. "An emergence of evidence, including the stuff we found, indicates that they underwent the same kind of evolution as whales, and they became streamlined."

Fossilized skin

As a group, the mosasaurs varied from a little over 3 feet (1 meter) to almost 50 feet (15 meters) long. The fossilized skin and skeleton unearthed in Kansas in 1953 belonged to a mosasaur — Ectenosaurus clidastoindes —stretching some 16 feet (5 meters) in length, though only the front half of its body was discovered. It is a relatively primitive specimen and is estimated to be about 85 million years old.

The fossils suggest the mosasaur's scales were less than a tenth of an inch long (only a few millimeters). These scales were oval-shaped and had a ridge along the middle to help them lock together, channel water, and also to provide an area for the skin to attach underneath.

"You could see the scales from both the outside and the inside. That's a first. On the inside they have special supportive structures that … anchor to the soft tissue, and they provide a more efficient cover," Lindgren said. "The scales have a ridge on each scale that helps channel the water and provides a thin layer, you see the same thing in sharks today."

The study was published today (Nov. 16) in the journal PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.