I have a confession to make. "Godwin's Law" regarding Nazi comparisons has been a staple of online communities for years, but I never connected the idea to Mike Godwin. Godwin was an early Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) attorney who played a key role in bringing down the 1996 Communications Decency Act; last year, he served top lawyer for the Wikimedia Foundation and shot off a wonderfully snarky letter (PDF) to the FBI over Wikipedia's use of their seal.

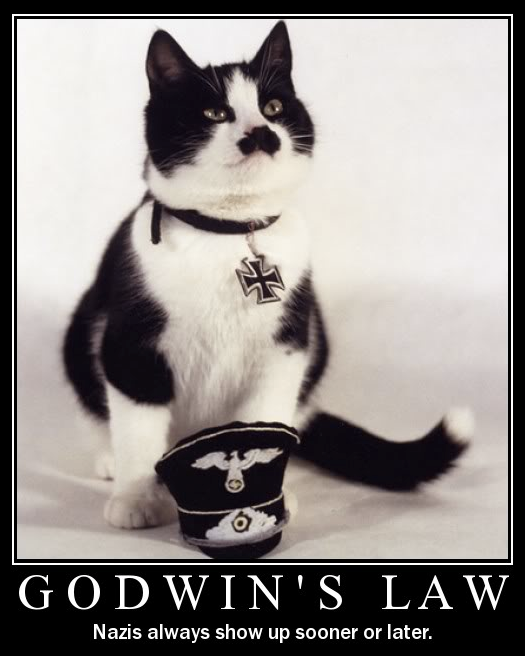

But not until I recently started reading his 1998 book Cyber Rights did I have one of those electric moments of connection: Mike Godwin created Godwin's Law. On the off chance that you've been living under the same rock I have, here's why he did it—and what it might mean for our own online ethical duties.

Find a new rhetorical hammer

In 1990, Godwin got fed up with Nazi comparisons on bulletin boards, Usenet newsgroups, and the WELL discussion site. So prevalent had these comparisons become that Godwin began to wonder “how debates had ever occurred without having that handy rhetorical hammer.”

He believed that most of these comparisons simply trivialized the Holocaust and the true horror of the Nazi regime and so consciously decided to build a “countermeme designed to make discussion participants see how they were (and are) acting as vectors to a particularly silly and offensive meme.” The result was Godwin's Law in its original form:

As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.

Godwin began dropping his law into various newsgroups that he frequented, where it picked up a life of its own. Discussion participants quickly began citing the law and created their own corollaries to it; Sircar's Corollary stated, for instance, “If the Usenet discussion touches on homosexuality or Heinlein, Nazis or Hitler are mentioned within three days.” A discussion thread was said to be "Godwinned" once a Hitler/Nazi comparison surfaced, and was widely assumed to have ended its useful life. When a "Godwin" happened in the thread title, as with 2003's "Reminds me of the Third Reich" topic in the Ars forums, people grew exasperated. "Do we have to kick Godwin's law into action in the topic? Really, can this thread lead to anything constructive?"

Twenty-one years later, Godwin's success is simple to measure. A Google search returns 599,000 results for “Godwin's Law,” with more than 600 mentions in the Ars Technica forums alone. Still, just knowing about the law doesn't necessary halt Nazi comparisons—it just means that people make them more consciously. "I can't help but Godwin the thread," wrote one Ars commenter back in 2008. "Watching Lindsey Graham speak, I now know what Germans felt like watching Nazi rallies in the early 30s."

Eventually, the law grew so widely cited that it spawned a backlash from those who thought Nazi comparisons could be perfectly valid. As one Ars forum denizen put it last year, "I never really got the Godwin's law rule. Nazi Germany was a reality and should be used as any part of history would be. If I have a valid point that I can make about something and it is directly quantifiable with Nazi Germany, the point is still valid. Just because I mention Nazi Germany doesn't invalidate it Are we going to change this rule every time a new evil force comes along, negating the current Godwin's law? The next law will be Bin Laden's law?"

Salon.com columnist Glenn Greenwald devoted an entire column to the topic, arguing that "the very notion that a major 20th Century event like German aggression is off-limits in political discussions is both arbitrary and anti-intellectual in the extreme. There simply are instances where such comparisons uniquely illuminate important truths."

Mother Jones writer Kevin Drum called the law "an endlessly tiresome way of feigning moral indignation" and hoped for its "repeal."

And as far back as 2005, libertarian writer Dave Weigel wrote that we'd all be "better off rolling back Godwin's Law and admitting the all-purpose usefulness of Nazi analogies."

A duty to remember

But Godwin never meant the law to cover all Nazi comparisons, only "glib comparisons," as he wrote in a follow-up note to Greenwald. Godwin reflected on the law in a 2008 piece for Jewcy:

I sometimes have some ambivalence about the law, which is far beyond my control these days When I saw the photographs from Abu Ghraib, for example, I understood instantly the connection between the humiliations inflicted there and the ones the Nazis imposed upon death camp inmates—but I am the one person in the world least able to draw attention to that valid comparison.

Overall, though, I'm content that the law has as much popcult traction as it does. My feeling is that "Never Again" loses its meaning if we don't regularly remind ourselves of the terrible inflection point marked in human culture by the Holocaust Key to that obligation is remembering, which is what Godwin's Law is all about.

When he saw the success his counter-meme had, Godwin began pondering the ethics of the situation—if destructive memes could spread virus-like through Internet society, did people have a positive ethical duty to create counter-memes? In Cyber Rights, he put it this way:

When we see a bad or false meme go by, should we take pains to chase it with a countermeme? Do we have an obligation to improve our informational environment? The time has come, I think, for good netizens and committed First Amendment supporters to commit ourselves to memetic engineering—crafting good memes that improve society as well as "anti-viral" countermemes that may neutralize and even eliminate the bad memes floating around out there on the Net and in society at large.

Which, of course, made me feel a bit guilty; while Mike Godwin has done his part to cleanse the Internet of glib Nazi comparisons, I've done no counter-meme creation of my own to clean up Internet discussion. My colleague Peter Bright suggested Bright's Law as a starting point: "If you cannot work out whether someone is trolling or merely stupid, the answer is probably both." Perhaps the Ars community can do better?

reader comments

228