A group of Texas voters seeking to stop the use of paperless electronic voting machines reached a dead end on Friday; the Texas Supreme Court ruled that their suits could not proceed without evidence that they have been personally harmed.

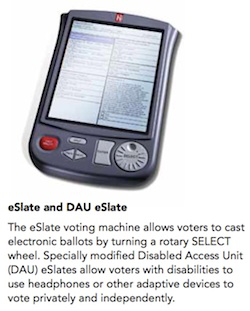

Texas has been using direct-recording electronic (DRE) voting machines for more than a decade. In 2006, a coalition of voters led by the Austin NAACP sued to stop Travis County from using the eSlate, a DRE machine made by Austin-based Hart InterCivic. (Hart does offer a printer as an optional component of its system.) The voters claimed the machines were insecure and did not allow meaningful recounts.

Travis County disagreed. In a FAQ on the county's voting website, officials answered questions about paper trails and security.

Q: Some computer experts claim that there is no way to audit the vote without a paper trail. Does this system have paper backup?

A: This system provides voters with confidence that their vote will be counted as they intended. First, the voting device provides each voter with a summary of all votes, alerting the voter of any skipped races, and allowing the voter to make changes. The voter has visual confirmation that the vote was cast exactly as intended. To ensure the votes are recorded correctly, the system is publicly tested and validated before, during, after each election to ensure that votes are counted and reported as they are cast. There are many security features designed to test procedures, equipment and software. Finally, the system can print out all Cast Vote Records should that be required for a recount.

In other words, the county has foregone a real paper trail, but it can simply print all the vote records in the machine's memory on slips of paper at a later date. Since the concern in most such cases would be about whether the recorded votes are accurate—not, say, whether the computer was adding them up properly—this feature is largely meaningless. (A real paper trail prints a "receipt" under glass that voters can see before leaving the voting station.)

A lower court rejected the Texas Secretary of State's request to dismiss the case before trial. But the state's highest court overturned that ruling. "We cannot say the Secretary's decision to certify this device violated the voters' equal protection rights or that the voters can pursue generalized grievances about the lawfulness of her acts," the Supreme Court wrote.

"Derelict in her duty"

Ars talked to Dan Wallach, a Rice University professor of computer science who served as the plaintiffs' expert witness. He expressed exasperation at the result. In essence, Wallach said, the Supreme Court has deferred to the judgement of the state legislature and the Secretary of State.

However, he said, "The whole point of the lawsuit is that the Secretary of State has been derelict in her duties." The ruling leaves Texas voters with limited meaningful remedies when election officials fail to comply with state law. The ruling suggests that the courts will only get involved if voting machine flaws actually disrupt an election and the losing candidate is prepared to challenge the result in court.

That bothers Joseph Lorenzo Hall, a University of California-Berkeley e-voting scholar, who pointed out that the Travis County machines lack a voter-verified paper trail. That means they "don't keep the type of evidence you'd need to prove these types of harms." So if a DRE machine did alter the outcome of an election, there might be no way to prove it after the fact.

Flawed technology

Wallach is an expert on Travis County's eSlate machines because he participated in one of the nation's only comprehensive DRE machine security audits in California back in 2007. Wallach says the most serious flaws with the machines arise from their networking capabilities. To tally the votes at the end of the election, the Hart InterCivic's voting machines are taken to a distribution center where they are connected to an ordinary PC running special vote-counting software.

Wallach said that the PC software had a buffer overflow vulnerability, which meant that a single malicious voting machine could take control of the vote-counting PC. And the PC, in turn, had the power to directly modify the memory of the other voting machines which would later be connected to it. Hence, a malicious party with access to a single voting machine could trigger a viral attack on the voting machines used in dozens of precincts.

Hall pointed to another security flaw. "There's a port on the back of the machine that will authorize a large number of 4-digit PINs," he said. Each PIN allows the casting of one vote. So if poll workers weren't paying close attention, an unscrupulous voter with a small portable device could use this vulnerability to cast a large number of votes.

Friday's ruling means Wallach won't get to point these flaws out at trial. "DREs are not perfect. No voting system is," the high court wrote. It was satisfied that the Texas Secretary of State "made a reasonable, nondiscriminatory choice to certify the eSlate, a decision justified by the State's important regulatory interests."

A national pattern

Hall told Ars that the Texas outcome has been mirrored across the country. Courts have been reluctant to second-guess the administrative decisions of the elected branches of government. In 2003, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected a challenge to California's use of DRE voting machines, holding that the choice of machines was at the discretion of state officials there. The Eleventh Circuit used similar reasoning to reject a challenge to Florida's use of DRE machines in 2006. The Texas Supreme Court cited both decisions in its ruling on Friday.

Activists concerned that DRE machines threaten the integrity of elections will have to make their concerns felt through the electoral process. Perhaps the most successful example of this occurred in California. After the courts rebuffed efforts to challenge the use of DREs through litigation, California voters elected Debra Bowen as Secretary of State in 2006. The next year, she conducted a comprehensive review of voting machine security with the help of Wallach, Hall, and numerous other voting and computer security experts. The results caused her to decertify a number of machines, including the eSlate, until the vendor fixed the flaws the researchers discovered.

So far, efforts to get elected officials in Texas to address security concerns with DRE voting have been unsuccessful. The state legislature has repeatedly considered, but failed to enact, legislation requiring voting machines there to have a voter-verified paper trail. With the judicial route foreclosed, now might be a good time to renew the push for auditable elections through the electoral process.

Listing image by Photo by William Clifford

reader comments

95