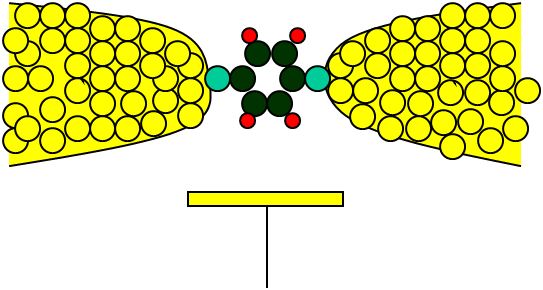

Sometimes the intersection of physics, engineering, and "we want the shiny" can be a bit weird. In the drive to smaller and more efficient electronic devices, some are trying to shrink existing approaches, while others are heading straight to the ultimate end point: using molecules to do everything. The basic idea is that electronic conduction through a molecule can be controlled by using electrons to modify the electronic or physical configuration of the molecule. Since it may only take a few femtoseconds (10-15s) to change this state, chemists paint pictures of high-speed electronic nirvana. The automatic response is: "Let's build it NOOOOW."

As any good scientist would do, when these ideas were suggested, they didn't think too hard about whether it would work; instead, they just tried it. It wasn't easy, but examples of molecular conductors are littered throughout the scientific record. In real life, these molecules worked, but nowhere near well enough to make devices. With some time to think about things, scientists were faced with a pressing question: why the hell do these things work at all? Handwaving explanations have abounded, but now, a good robust explanation has been put forward.

Oh no, he's going to mention interference

Our normal picture of conduction is that metals have a bunch of electrons that are free to roam around. If we apply a force to them, they will move and we can make them do work. In semiconductors, there are far fewer free electrons around, but we can inject or remove electrons to turn semiconductors into conductors or nonconductors, making a switch.

In both cases, the electrons can basically be treated like point particles bouncing their way through a material, a bit like a drunk Little Red Riding Hood on her way to deliver grandma her hit.

Molecules are not like that. Electrons in molecules are more like waves. To travel from one part of a molecule to another, the different paths have to add up in phase (the key concept here is quantum superposition). That is, the electron takes all possible paths from a to b, and, if all those paths interfere constructively, the electron will find itself at b, perched on the couch wondering where the beer fridge is.

This is also true for the case where an electron wants to jump from the molecule to a nearby piece of metal or back. There is a catch, though. If you add up all the paths that start on a metal lead and terminate on a lead, then in general you find that they always cancel out. This cancellation is actually a fundamental property of the wave nature of quantum particles and cannot be avoided. But it also raises a very important point: if the paths all cancel out, why can I pass current through a molecular junction?

Nooo, anything but coherence

The answer lies in the coherence of the electrons as they traverse the molecule. In the perfect situation, where a molecule is sitting all by itself, everything stays coherent and the electrons have perfect interference. But just by joining a molecule to a metal wire, we disturb that delicate balance and, with it, the perfect interference. In fact, even without the metal, the molecule is continually in motion—the bonds between atoms vibrate and rotate—but the metal ensures that this motion is very stop-start.

The thing about molecular vibrations is that they have specific frequencies, called modes. A mode can be excited, after which it will vibrate for a while and then stop. The length of time that it will vibrate is very important because the electron will take the vibrational motion into account as it travels.

The metal causes the vibrational modes to start and stop again very quickly. It is this combination of many different vibrational modes, and their stop-start nature, that destroys the coherence between the various paths. Essentially, you can think of the vibrational modes as randomly creating hills and valleys along the paths. These make some paths impossible for a small section of time, removing the interference. The end result being that, at any particular time, the electron will take a single path.

Those were just general calculations. The researchers also considered a real molecular system and found that their calculations predict its conductivity pretty well. Better yet, because it is so general, it will be widely applicable to other molecules and conductors that rely on interference for conduction.

Physical Review Letters, 2011, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.046802

Listing image by Photograph by Rice.edu

reader comments

33