'Twilight' Bacteria May Be Missing Link in Global Carbon Cycle

In the dark depths of the ocean, mysterious organisms have been converting carbon dioxide into a form useful for life. Now scientists have identified some suspects: "twilight" microbes from 2,625 feet (800 meters) below the ocean surface that are turning inorganic carbon into useable food.

The job of capturing carbon, crucial to sustaining life on Earth, is usually carried out by plants that use sunlight as energy. But light doesn't penetrate below 656 feet (200 meters) of ocean, so plants can't do this job. [The Harshest Environments on Earth]

To survive, living cells must convert carbon dioxide into molecules that can form cellular structures or be used in metabolic processes. Simple, single-celled organisms called archaea that often live in extreme conditions were thought to be responsible for much of the dark ocean's carbon fixation. But there was evidence that archaea could not account for the total amount of carbon fixation going on there.

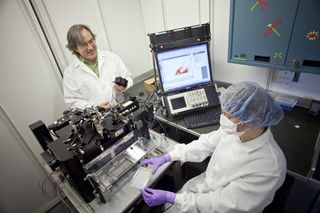

"Our study discovered specific types of bacteria, rather than archaea, and their likely energy sources that may be responsible for this major, unaccounted component of the dark ocean carbon cycle," said Ramunas Stepanauskas, a study researcher who is director of the Bigelow Laboratory Single Cell Genomics Center.

To get a glimpse of what was going on in the dark, the researchers looked at samples from two subtropical gyres, or systems of rotating ocean currents, in the South Atlantic and North Pacific. The team isolated single cells from the samples and sequenced genomes (the complete set of inherited instructions for an organism) of 738. This allowed them to identify a variety of strains of bacteria and verify the predominant lineages capable of fixing carbon.

To carry out this process, cells need a source of energy. While it is believed that archaea use ammonia, many of the bacteria the scientists sampled contained genes suggesting they could use sulfur compounds as an energy source. Others may also use single-carbon compounds, like methane, as energy sources, the researchers write.

These previously unrecognized types of dark ocean bacteria may play an important role in the natural cycling of nutrients from the environment to organisms and back, the researchers write in the Sept. 2 issue of the journal Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You can follow Live Science writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.