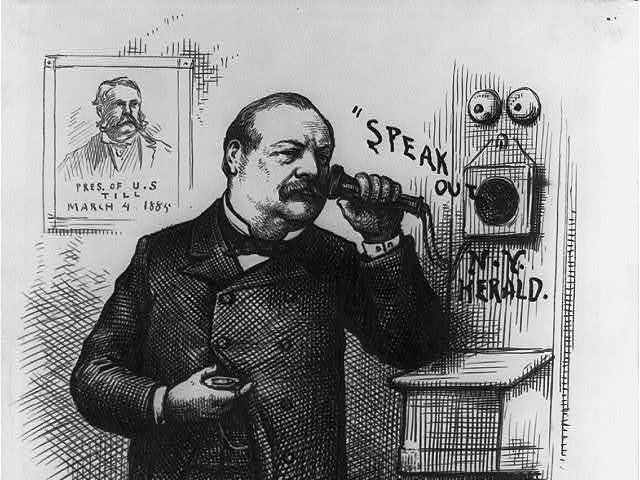

Hopping mad about metered billing? Spluttering about tethering restrictions and early termination fees? Raging over data caps? You're not alone. Perhaps you can take some comfort from this editorial in The New York Times:

The greedy and extortionate nature of the telephone monopoly is notorious. Controlling a means of communication which has now become indispensable to the business and social life of the country, the company takes advantage of the public's need to force from it every year an extortionate tribute.

Yes, that's how The Times saw it—in 1886. And the newspaper's readers applauded these words. But reading Richard R. John's wonderful book, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications, one is struck by the contrasts between then and now. The issues are often recognizable; the players a little less so.

Nothing whatever

It was 1887, and Charles M. Fay, General Manager of the Chicago Telephone Exchange, had had about as much as he could take. The pseudo populist legislatures that kowtowed to telephone subscriber groups were on a rampage, Fay warned in a lengthy screed that appeared in the National Telephone Exchange Association's annual journal. Now they were demanding rate caps and price regulation—but for whom?

The poor and working class have "nothing whatever" to do with the telephone, and never will, Fay insisted. "Telephone users are men whose business is so extended and whose time is so valuable as to demand rapid and universal communication," he continued, leaving to posterity this remarkable claim about the service:

A laborer who goes to work with his dinner basket has no occasion to telephone home that he will be late to dinner; the small householder, whose grocer lives just around corner, would not pay once cent for a telephone wherewith to reach him; the villager, whose deliberate pace is never hurried, will walk every time the few steps necessary to see his neighbor in order to save a nickel. The telephone, like the telegraph, post office and the railroad, is only upon extraordinary occasions used or needed by the poor. It is demanded, and daily depended upon, and should be liberally paid for by the capitalist, mercantile, and manufacturing classes.

To be fair, Fay was right about the immediate moment. Given 1887 telephone subscription rates, hardly any workers or villagers bought regular telephone service. They couldn't afford it. But the Bell System's big problem in 1887 wasn't the poor and struggling masses. It was those "mercantile and manufacturing" types—also up in arms at Bell franchise prices.

Appalled at schemes like "measured service" for billing consumers for local calls, telephone subscribers launched municipal and state-wide reform campaigns, backed independent network providers, and ran "rate strikes" on more than one occasion.

"Telephomania," Fay bitterly called the phenomenon—the "only fit word" to describe these ingrates. But their largely forgotten uprisings made a difference.

"By demonstrating the vulnerability of operating companies to legislative intervention," writes John, "they goaded a new generation of telephone managers into providing telephone service to thousands of potential telephone users whom their predecessors had ignored. The popularization of the telephone was the result."

Countless threads of wire

A quick refresher on the early history of the telephone: Alexander Graham Bell obtained his electrical transmission patent in March 1876 and his telephone device patent about ten months later. In 1878, investors formed the National Bell company to make money from the patents. Western Union launched a rival exchange, but in 1879 ceded the business for a share of Bell's profits.

Equipped with Western Union's fifty or so fledgling exchanges, National Bell reorganized as American Bell. The company provided no telephone service. Instead, it licensed its patents and collected fees from locally based operating companies, which leased equipment and sold service to consumers.

American Bell made remarkable profit margins in the 1880s. They "hovered around 46 percent," John notes. Bell put some of these earnings back into the business; the rest went to shareholders. Not surprisingly, most Bell stockholders didn't sell their stock.

But while Bell became a company beloved by investors, the era of good feelings between the local operating franchises and their subscribers was short lived.

The overhead wire problem came first. Thanks to extant telegraph lines and New York City's new telephone exchange, the sky around Gotham had become darkened by "countless threads of wire," complained an English tourist in 1881.

This was more than just an aesthetic problem. One day walkers near New York City Hall looked up to see a horrible sight—the body of a Western Union lineman electrocuted by a stray wire. His corpse swayed about in full view for several hours before someone cut him down. Telegraph and telephone exchanges used low voltage lines, of course, but power companies did not, and the wiring systems of all three utilities sometimes got tangled.

When a Buffalo, New York operating company was sued in 1888 for a similar tragedy, the jury damned overhead wires as "secret and deadly traps to human life."

In response, city and state legislatures ordered the exchanges to tear their trapezes down and replace them with underground conduits. Manhattan buried its last aerial telephone cables in 1896. Other companies followed suit, albeit with considerable grumbling by their principals. An underground wire law was the "severest attack" that the telephone industry had yet to confront, warned Morris F. Tyler, President of Connecticut's Bell operating company. But this issue was only a taste of telephone wars to come.

The "Dead Head Evil"

At the dawn of local exchange telephony, most consumers were charged a "flat rate" within a given exchange territory. Some of these areas were only a few square miles (Chicago's was about 16.3 in 1889). As the exchange grew, so did the flat rate zone. Subscribers who wanted to reach someone beyond the unlimited access region paid an extra fee called a toll.

Subscribers liked flat rates, of course, since they were predictable. Operators quickly became less fond of them. "Most obviously, they increased operating costs as the exchange expanded," historian John notes. "Subscribers had no incentive to limit the number of outgoing calls, and, as the number of subscribers in the unlimited access zone expanded, they had more people to call."

Worst of all, from the operator point of view, was what one journalist called the "Telephone Dead Head Evil"—non-subscribers using the telephone of a subscriber; for instance, patrons of a local drug store using the phone for a nickel a call.

One Edward J. Hall of the Buffalo, New York exchange had a solution for this: measured service. Hall's plan consisted of a rental tithe for the telephone, plus ten cents for each telephone call. Consumers had to make at least 500 calls a year under this plan. Hall had a package for non-subscribers too: prepaid tickets that permitted the buyer a fixed number of calls.

Not all carriers liked this idea. Flat rates were simple. Measured service required additional bookkeeping. But these sort of plans had an attractive political advantage, John observes. "As long as operating companies charged every subscriber an identical monthly fee, subscribers had an obvious rallying cry: keep the rate low." Measured service "spoilt the unanimity" of fixed rates, Hall gleefully observed, making it harder for subscribers to protest their fees to legislators.

And that's why the first telephone consumers tried to kill measured service from the start.

reader comments

93