The woman sitting in front of me on this plane seems perfectly nice. She, like me, is traveling coach class from Washington to Los Angeles. She had a nice chat before takeoff with the man sitting next to her, in which she revealed she is an elementary school teacher, an extremely honorable profession. She, like me, has an aisle seat and has spent most of the flight watching TV. Nevertheless, I hate her.

Why? She’s a recliner.

For the five minutes after takeoff, every passenger on an airliner exists in a state of nature. Everyone is equally as uncomfortable as everyone else—well, at least everyone who doesn’t have the advantage of first class seating or the disadvantage of being over 6 feet tall. The passengers are blank slates, subjects of an experiment in morality which begins the moment the seat-belt light turns off.

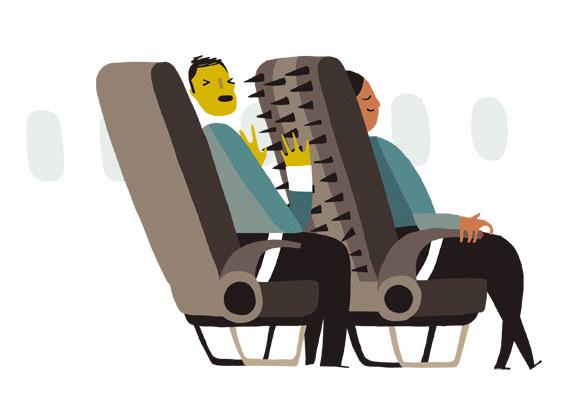

Ding! Instantly the jerk in 11C reclines his seat all the way back. The guy in 12C, his book shoved into his face, reclines as well. 13C goes next. And soon the reclining has cascaded like rows of dominos to the back of the plane, where the poor bastards in the last row see their personal space reduced to about a cubic foot.

Or else there are those, like me, who refuse to be so rude as to inconvenience the passengers behind us. Here I sit, fuming, all the way from IAD to LAX, the deceptively nice-seeming schoolteacher’s seat back so close to my chin that to watch TV I must nearly cross my eyes. To type on this laptop while still fully opening the screen requires me to jam the laptop’s edge into my stomach.

Obviously, everyone on the plane would be better off if no one reclined; the minor gain in comfort when you tilt your seat back 5 degrees is certainly offset by the discomfort when the person in front of you does the same. But of course someone always will recline her seat, like the people in the first row, or the woman in front of me, whom I hate. (At least we’re not in the middle seat. People who recline middle seats are history’s greatest monsters.)

What options do we, the reclined-upon, have? We can purchase the Knee Defender, a product which snaps onto the tray table and prevents the passenger seated in front of us from reclining their seat. But that seems fraught with potential awkward complications. What if the person ahead of you protests? What if the flight attendant gets angry? (The website for Knee Defenders even acknowledges these difficulties with a whole page titled “Etiquette on Airplanes”—and offers printable “courtesy cards” to hand to the person in front of you.)

Lacking a Knee Defender, you can politely ask the person in front of you not to recline. But then the person in front of you is filled with resentment, because he feels you have forced him to give up his comfort in favor of yours. (Plus, the person in front of him may have reclined her seat.)

And it might not even work. Once, on a flight from Chicago to Honolulu, a sweet old Hawaiian lady and her husband sat in front of me, and both reclined their seats at the very beginning of the eight-hour trip. “Excuse me,” I said. “That’s very uncomfortable. Is there any chance you could put your seat back up, at least partway?”

“No!” she snapped. “We paid for these goddamn seats, and we’ll recline them if we want to.” So then everyone was angry: I was angry because I had no room, and she was angry because I passive-aggressively kicked her seat once every 15 minutes—often enough to be annoying, but not often enough to definitely be on purpose.

The problem isn’t with passengers, though the evidence demonstrates that many passengers are little better than sociopaths acting only for their own good. The problem is with the plane. In a closed system in which just one recliner out of 200 passengers can ruin it for dozens of people, it is too much to expect that everyone will act in the interest of the common good. People recline their seats because their seats recline. But why on earth do seats recline? Wouldn’t it be better for everyone if seats simply didn’t?

Reclining seats have been with us as long as airlines began making human passengers a priority. In the 1920s and 1930s, people were an afterthought; planes were meant to carry airmail and cargo, and any humans who wanted to come along were welcome to pay an astronomical fare and sit in wicker chairs. “Reclining seats were not a universal treatment until the DC-3 era,” beginning in 1935, says John Hill, assistant director in charge of aviation at the SFO Museum. In the beginning, reclining seats—along with footrests and in-seat ashtrays—were designed as part of airlines’ commitment to deluxe accommodations, as captains of industry in three-piece suits sipped martinis on board, stretching their legs one way and tilting their seats the other.

The seats persisted, even as airlines moved to the tiered service model we know now, which required packing more and more customers into economy in order to keep RPK (revenue per kilometer) high. “They didn’t want to give up the idea of luxury altogether,” Hill notes. But these days, flying is simply an ordeal to be survived. In the era of cheap tickets and passengers crammed onto flights like sardines, reclining seats make no sense.

That’s why the woman in front of me does not really deserve my hatred. (Although would it kill her to straighten her seat back even a little when she goes to the bathroom?) Miss Manners agrees: The real offending party is the airline—in this case, Virgin America. They installed stylish purple lighting and sleek leatheresque seats in this A320 jet; they serve much better food than you might expect; even their in-flight safety video is endearingly written and animated. And the seats on Virgin (and every airline, really) are a marvel: “One of the most highly tuned man-made environments, period,” Hill notes, “optimized for space and weight and safety.” But despite all these nods toward modern, customer-friendly design, Virgin still, in opposition to all that is right and good, installs reclining seats on their planes. Just like everyone else.

Some European airlines have begun installing seats that are slightly tilted in their natural resting state, which, anecdotally at least, helps convince passengers they don’t need to tilt further. But that doesn’t go far enough. It’s time for an outright ban on reclining seats on airplanes. I’m not demanding that airlines rip out the old seats and install new ones; let’s just extend the requirement that seats remain upright during takeoff and landing through the entire flight. (Unlike the stupid electronic-devices rules, there is an actual good reason for this regulation: Upright seats are safer in a crash, and allow for easier evacuation.) To those who say such a rule is unenforceable, I respond: Kick. Kick. Kick.

Of course, this whole debate has a limited shelf life. Ten years from now, if financially strapped American carriers exist at all, they’ll surely have gone the way of budget European airline Ryanair, with its nonreclining seats—and horrifying 30-inch seat pitch. When I fly in one of those planes of the future, will I be comfortable? Absolutely not. But I won’t complain, because at least everyone else will be exactly as uncomfortable as me.