When David Kappos announced his resignation as head of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) late last year, one of his most touted accomplishments was a significant reduction in the backlog of pending patent applications. Kappos' fans have attributed this to the hiring of hundreds of additional patent examiners.

But a new study suggests another explanation for the declining backlog: the patent office may have lowered its standards, approving many patents that would have been (and in some cases, had been) rejected under the administration of George W. Bush. The authors—Chris Cotropia and Cecil Quillen of the University of Richmond and independent researcher Ogden Webster—used Freedom of Information Act requests to obtain detailed data about the fate of patent applications considered by the USPTO since 1996.

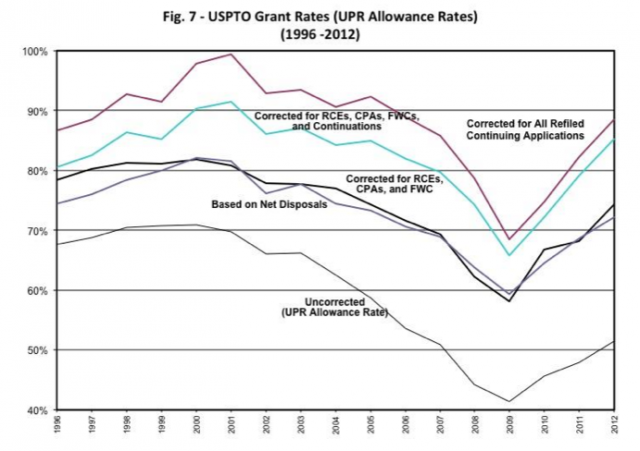

They found that the "allowance rate," the fraction of applications approved by the patent office, declined steadily from 2001 and 2009. But in the last four years there's been a sharp reversal, with a 2012 allowance rate about 20 percent higher than it was in 2009.

Patent pending

Calculating the real allowance rate is tricky because inventors can submit the same application multiple times. "From the perspective of the patent office, a 'final rejection' doesn't get rid of an application," Quillen told Ars in a December phone interview. If an application is rejected, the inventor can make minor changes to the application and file it again. "The only way you can reduce your numbers and get rid of somebody is to allow the case," Quillen said.

There are a number of different ways to re-file applications, with names like File Wrapper Continuations, Continued Prosecution Applications, Requests for Continued Examination and Continuation-In-Part Applications. But in all cases, the upshot is the same: the applicant gets another shot at convincing examiners to grant him a patent.

The ease with which applicants can re-file the same application leads to misleading official statistics suggesting the patent office is pickier than it really is. If an examiner rejects an application twice before finally granting a patent on the third try, that might be counted as two rejections and one acceptance, for a 33 percent acceptance rate. But it probably makes more sense to consider the three filings as part of the same application process, for a 100 percent acceptance rate.

Cotropia and his colleagues gathered data on re-filed applications to correct for this problem. The result was this graph:

The bottom line shows the "raw" allowance rate: the fraction of applications that got a thumbs-up from patent examiners. (UPR is "utility, plant, and reissue," three categories of patent.) The next few lines shows the allowance rate after combining applications to avoid double-counting those that have been submitted more than once. The top line shows the result when all types of re-filing are accounted for.

The graph suggests that the patent office got steadily pickier during the presidency of George W. Bush. The uncorrected allowance rate fell from about 70 percent to a bit over 40 percent during Bush's eight years in office. Then after Obama appointed David Kappos to the patent office, the allowance rate rose back above 50 percent.

And the reversal looks even more dramatic after correcting for re-filed applications. The corrected allowance rate (the purple line) rose from 70 percent at the beginning of Kappos' tenure to almost 90 percent by the end.

Third time is a charm

"We made a conscious decision simply to present the facts and leave their interpretation to others," Quillen told Ars in a March e-mail. But James Bessen, a Boston University researcher whose work we've covered before, told us that the obvious interpretation was the correct one.

"The backlog is in patent applications that have been rejected, that should be rejected, but which patent office rules allow to be endlessly refiled," Bessen told us by e-mail. "The surge in allowance under Kappos is a sharp change from previous grant rates."

Of course, it's theoretically possible that the quality of patent applications suddenly started rising in 2009. But Bessen argued that was unlikely. He pointed that a lot of the current backlog consists of re-filed applications that were rejected the first time around. And he pointed to a recent study estimating that 28 percent of current patents would be found invalid by the courts, suggesting that the patent office has not done a thorough job of screening the patents.

Naturally, the USPTO disagrees with Bessen's interpretation of the data.

"Patents that are subject to a longer wait time for a first action tend to abandon at higher rates than other applications (holding all other factors constant)," a spokesman told us by e-mail. "The higher level of abandonment leads to a lower observed grant rate, measured by grants as a proportion of total disposals. Conversely, when first action pendency falls across the board, there are fewer abandonments and the grant rate rises."

In other words, the patent office says that when applicants have to wait a long time for a response, they tend to just give up. Now that the wait time is down, thanks to PTO efficiency, fewer of them are giving up. As a result, the ratio of accepted patents to rejected patents whose owners don't try again might go up even if the patent office hasn't lowered its standards.

That argument "ignores the fact that the increased backlog comes from patents that were already rejected, but then refiled," Bessen told us. "What matters is not the quality of the average patent examination, but rather the quality of the last examination," the one that leads to the patent either being granted or the applicant choosing not to re-file it.

The fundamental problem, both Quillen and Bessen agree, is that the only way to get rid of a persistent applicant is by giving him a patent. "Refiled continuing applications should be abolished," Quillen told us in a March e-mail. "This would enable the USPTO to obtain final decisions as to the patentability of applications it has examined, and would eliminate the rework that such refiled applications impose on the USPTO." That would free up resources for the USPTO to examine new applications more thoroughly.

reader comments

39