Raspberry Pi has received the lion's share of attention devoted to cheap, single-board computers in the past year. But long before the Pi was a gleam in its creators' eyes, there was the Arduino.

Unveiled in 2005, Arduino boards don't have the CPU horsepower of a Raspberry Pi. They don't run a full PC operating system either. Arduino isn't obsolete, though—in fact, its plethora of connectivity options makes it the better choice for many electronics projects.

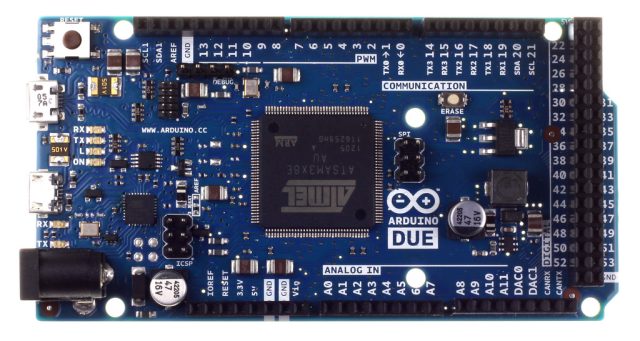

While the Pi has 26 GPIO (general purpose input/output) pins that can be programmed to do various tasks, the Arduino DUE (the latest Arduino released in October 2012) has 54 digital I/O pins, 12 analog input pins, and two analog output pins. Among those 54 digital I/O pins, 12 provide pulse-width modulation (PWM) output.

Arduino's array of inputs and outputs proves crucial in projects from building robots to 3D printers, said Jason Kridner, co-creator of the BeagleBone line of products that combine Raspberry Pi-like horsepower with Arduino-like capabilities.

Pulse-width modulation, for example, is important for driving motors in particular directions and telling them how fast to go, Kridner recently explained to Ars. "If you wanted to do that with a Raspberry Pi, you'd essentially have to add an Arduino," he said. (The Raspberry Pi does have one pin capable of outputting a PWM signal, and software can add PWM capability to the other pins with some limitations.)

Last December, we featured 10 of the most amazing Raspberry Pi projects, including arcade cabinets, robotics, and a wearable computer. This one goes to 11—as in, we'll show you 11 awesome things hackers and electronics enthusiasts have created with the Arduino.

These projects take some serious skill—and, in a couple cases, a disregard for one's own safety.

Giving “sight” to the blind with Arduino and the human tongue

When a person loses the ability to see, the senses of hearing, touch, and smell are relied on even more to navigate one's surroundings. But the tongue could be used for the same purpose, with the help of an Arduino-fueled contraption called the Tongueduino.

Devised by MIT researcher Gershon Dublon, Tongueduino sends information to a pad that has electrodes spread across a grid. This pad is placed into the user's mouth. "When hooked up to an electronic sensor, the pad converts signals from the sensor into small pulses of electric current across the grid, which the tongue 'reads' as a pattern of tingles," New Scientist reported in February.

"The tongue is known to have an extremely dense sensing resolution as well as a high degree of neuroplasticity, the ability to adapt to new input," according to the MIT Media Lab video embedded above. "Research has shown that electrotactile tongue displays can be used as vision prosthetics for the blind. Users quickly learn to read and navigate through natural environments."

With Tongueduino, "[s]ignals map spatially and intensity maps to the number of pulses within a frame," the video states. In one example, a Tongueduino user is able to identify the pixels and lines drawn on a 3x3 grid by a colleague on a computer across the room.

The ultimate goal is to move beyond simple vision replacement toward greater sensory augmentation. A connection to a magnetometer could provide a user with "an internal sense of direction, like a migratory bird."

Dublon spent a year testing Tongueduino on himself. Having honed the design and upgraded the pad from a 3×3 grid to a 5×5 grid, he is now beginning to test it on a dozen volunteers.

Exterminate, annihilate, destroy! (Yes, it’s a Dalek)

This one goes out to all the Doctor Who fans. Perhaps the Doctor's most iconic enemy, the alien mutants in robotic shells known as Daleks are simultaneously terrifying and hilarious.

Who fan Andy Grove set out to build one, smartly combining the Raspberry Pi and Arduino:

I have used an Arduino Uno to monitor two ultrasonic sensors in the base of the Dalek and send the results over the USB serial interface to a Raspberry Pi which then plays an MP3 clip. I used a separate Arduino board to provide sound to light functionality to drive the dome lights.

I could have achieved the results I needed using just the Arduino or the Raspberry Pi but it seems to me that the Arduino is better suited to low-level functions interacting directly with sensors and motors and so on, whereas the power of the Raspberry Pi is that it is a fully functional Linux computer for tasks requiring more computational power, and where I can easily use existing skills to leverage the Internet later on. Eventually I plan to put motors in the dome and a webcam in the eye so that the Dalek can look directly at people that approach. I also want to have a Web interface to be able to control behavior.

Putting together the electronics was faster than building the bulk of the robot, made mostly of plywood, cardboard, and papier-mâché. Grove got the Dalek ready for this past Halloween, saying "[t]he construction took five months, with some time spent working on it almost every weekend."

The finished Dalek was absolutely worth the effort. Not only does it look like a Dalek, it's also able to utter the evil robot species' evil catch phrase:

For those of you who don't watch Doctor Who and wonder why anyone would spend so much time building a Dalek, here's your answer:

A 3D-printed flying quadcopter drone

3D printing and flying drones are among the two most popular activities for Arduino owners. Here we have a project that combines both activities into one.

Numerous people have purchased quadcopter drones and then outfitted them with Arduino-based control systems. Instead of just buying a quadcopter, a team at the University of Victoria in British Columbia built one from scratch using parts spewed out by a 3D printer.

The parts fit together like this:

But there was more work to be done after that, which is where the Arduino and a "9 Degrees of Freedom" sensor stick entered the picture.

The quadcopter project team explains its work here:

The 9 Degrees of freedom sensor stick (9DOF) contains three sensors: an accelerometer, a gyroscope, and a magnetometer. Each sensor can be communicated with using I2C from analog pins 4 and 5 on the Arduino Uno. We powered the sensor stick using the 5 volts out available on the Arduino Uno. I2C also requires pull-up resistors on the data (SDA) and clock (SCL) buses. We used two pull up resistors soldered to the 5 volt output of the Arduino shield and SCL/SDA. To prevent the sensor from receiving too much noise during flight, the sensor was soldered to an Arduino ProtoShield on the pins. The other end of the 9DOF was glued to the shield. The source code for the project is based on the AeroQuad [open source quadcopter].

And yes, the 3D-printed, Arduino-powered quadcopter did take flight. Here it is:

reader comments

42