In the film Broadcast News, an oleaginous TV exec asks a newly redundant media worker if there is anything he can do. You know, to help at this difficult time. "Well, I certainly hope you'll die soon," replies his former employee.

Shane Allen's leaving speech as Channel 4's head of comedy was equally scabrous. "The thing about Channel 4 is that you were allowed to go too far, so Shane was taking advantage of that before he went to the BBC," said one guest at the do, at the Comedy Pub in London's West End last month. Some walked out. Others gave him the nickname "Shane Guevara".

Allen, who takes up his new post as the BBC's head of comedy in a few weeks, handed out T-shirts and balloons with the slogan "End the Hunt", a reference to C4's chief creative officer, Jay Hunt. He used a scene of Moses parting the Red Sea in The Ten Commandments to hail the achievement of former C4 chief executive Kevin Lygo and referred to him as "the glorious leader". By contrast, he used clips from One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest and A Clockwork Orange to dramatise how he thought things had gone wrong under Hunt, who came to C4 from the BBC in January last year.

To be sure, farewell speech score-settling and dyspeptic jeremiads about how C4 has lost its mojo are not rare. I wrote one such jeremiad five years ago and, fingers crossed, this won't be another. Let's see how it works out.

What made Allen's speech especially poignant and embarrassing were two things. First, his speech came as C4 marked its 30th anniversary. Way to rain on the broadcaster's parade, laughing boy. That said, C4 hasn't celebrated its 30th anniversary with the gusto that marked its 25th. Perhaps that's because it's got less to celebrate. Shameless, one of its few good drama series this millennium, has been axed, while Gok, Gordon, Mary Portas, Phill and Kirstie, Kevin, Davina and the rest of its tired roster of celebrity presenters haven't. Come Dine with Me is on incessantly, as if symbolising C4's dearth of creative ideas.

Celebrations, in any case, would have been slightly tarnished by events earlier this month. C4 has been condemned by Ofcom for Love Shaft, a kids' show featuring contestants talking about "massive tits" and "sluts" – broadcast on a weekend morning when small children were likely to be watching. In its defence, C4 said Love Shaft was "cheeky, witty and full of entendre and risqué banter". Yawn. Wouldn't it be nice if just one programme, apart from Songs of Praise, didn't rely on risqué banter to cover up its creative, moral and spiritual bankruptcy? Didn't the statement maker realise they meant "double entendre"? On the same day, the broadcaster was castigated by Ofcom for allowing its racing coverage to promote an offer from their bookie sponsors Ladbrokes. Admittedly, neither reproach was as serious as Ofcom's heavy criticism of C4 last year for broadcasting Frankie Boyle's joke about Katie Price's disabled son.

Second, Allen's speech was heartfelt. He told guests how, growing up as a child in a working-class family in Belfast in the 1980s, C4 made the only programmes that spoke to him. It was a lament for a lost age. Imagine when a TV channel could be inspiring, counter-cultural, anti-establishment, committed to diversity, a threat to civilisation to some and a confirmation it hadn't died under Thatcher for others.

When it started on 2 November 1982, C4 was conceived of as a public-service broadcaster, commercially self-funded yet publicly owned, originally by the Independent Broadcasting Authority. It was a hybrid, a proto-Prius, a funky alternative to broadcasting hegemony. It gave clean-up TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse conniptions. It gave voice to those who sucked on the fuzzy end of Thatcher's lollipop. It served hitherto neglected demographics – ethnic minorities, women, lesbians and gay men, the freaks who like their TV opera live.

"There's nothing worse than someone telling you how great Channel 4 was," said one TV producer who asked to remain nameless this week, "but the bottom line is that it has lost its raison d'etre. One problem is that the original Channel 4 was all about diversity and difference. Now the whole of British society is more diverse and more comfortable with difference. It can't go back to what it was, and it doesn't know what it is."

Not quite true. Jay Hunt claims to know what her channel is. C4 is about "irreverence" and "punching people on the nose", she told the Edinburgh International Television Festival in September. She was discussing Drugs Live, a show in which Keith Allen and Lionel Shriver, among others, took drugs live. The Guardian critic, under the headline "Channel 4's Drugs Live: warning, may bore your eyes off", accused the programme makers of jaded cynicism rather than bracing irreverence towards a vexed social issue, observing: "People like to get mashed, and TV producers like to turn their cameras on people getting mashed."

"The worry with Channel 4, not just under Jay Hunt but well before, is that its supposed transgressiveness becomes evidently cynical to commissioning editors and viewers alike," one former C4 producer told me. Hence, perhaps, C4's growing renown for satirisable programme titles. Win A Baby. Make Bradford British. Phone Sex Secrets. Embarrassing Bodies. I'm Spazticus. Mummifying Alan. My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding. The Boy Whose Skin Fell Off. The Undateables. Why I'm So Proud of My Four Weirdo Yet God-Given Moobs. I made the last one up, though I'm open to commissions.

But is it fair to blame Hunt for the channel's toxic and exploitative reputation? After all, she's only been there for nearly two years and the rot, if that's what it is, set in long before. In 2006, Sir Jeremy Isaacs, C4's first chief executive, lamented how the channel had become obsessed with adolescent transgression and sex. "Gordon Ramsay is hired to make a series called The F Word," he wrote in Prospect magazine. "Designer Vaginas is followed by the World's Biggest Penis." Hunt isn't responsible for that genital fixation. She didn't land C4 in trouble with the Gypsy groups over its depiction of that community. It wasn't her fault that C4 was hopelessly behind the curve in recognising viewers fetish for all things Danish (BBC4 got The Killing, while C4 tried – and failed – to follow up on its popularity with the lame US version of the same drama).

It's certainly true that Hunt has had to face stern criticism before. While at the BBC (where she rose to become BBC1 controller), she had to defend the corporation over Sachsgate and was accused by Miriam O'Reilly at the former-Countryfile presenter's employment tribunal of ageism, sexism and hating women. It's hard, though, not to warm to a woman whom loathsome Quentin Letts mauled under the headline "Lean-lipped, humourless, the killer kitten who is steering Auntie on to the rocks".

Is Hunt, having failed to steer the BBC to the rocks, going to do that for C4? Let's start with the case for the defence. "I worked with her very closely at the BBC. You certainly have to take the rough with the smooth," says Jana Bennett, former president of BBC worldwide channels. "She is a sharp analytical thinker about how you approach the position of the channel and has a strong sense of the competitive landscape. She therefore goes about the programming to solve problems of competition and how to reach an audience in a very forensic way. She's a very determined person and cares hugely about what she does and brings a restless energy to what she applies herself to."

Bennett cites Hunt's commission of The Day the Immigrants Left, a 2010 BBC1 documentary fronted by Evan Davis in which unemployed locals replaced immigrant workers in an East Anglian town in an experiment to find out if Britons were really workshy. "That's typical of her. Take something relevant and approach it differently from an ordinary documentary. It could have been dull, but it was ingenious. She's a bold thinker. She's not daunted by the challenges, and Channel 4 does have challenges to reach audiences when they are more fragmented than ever before."

David Abraham, C4's chief executive, says he hired her because "she has real steel and resilience" and because she can "work across the genres at a fast pace". "Jay's central to what's being achieved on a number of levels."

Hunt has been responsible for putting some expired TV goods out of their misery. At Edinburgh she announced that there will be no more series of its rating-grabbing, queasiness-inducing format My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding, only one-off specials. This week it was announced lamentably eccentric C4 racing presenter John McCririck was being put out to pasture.

So she at least has the savvy to tell when a franchise is past its sell-by date, and take action. Now she needs to listen to critic Gareth McLean and C4 historian Maggie Brown, who argue that she needs to take Come Dine with Me and hold its metaphorical face down in the figurative hot tub where in reality so many unedifying CDWM soirees have concluded over damp petits fours. "Had the show remained unadulterated rather than packed full of additives such as shouty vegan strippers, I'd wager it would have a great deal more life left in it now," said McLean.

Abraham demurs. "It's always right to question any franchise, but the reality is that we have more diverse programing than our competitors. We're much less reliant on one franchise than our competitors." But one reason C4 won't scrap CDWM soon is because of the channel's cross-subsidy policy: such advertising magnets bankroll Channel 4 News, as well as noble yet commercially hopeless documentaries.

CDWM's ubiquity notwithstanding, C4 does seem to be in better condition than it was six months ago. It has won a tranche of Royal Television Society, Bafta and Grierson awards this year – much to the surprise of critics. More importantly, it won plaudits for the way its Paralympics coverage changed attitudes towards disability among viewers. I dreaded the prospect of I'm Spazticus, fearing exploitation at its worst, but it was a jolly prank show with a twist. Think Fonejacker where prankers are amputees, blind, have cerebral palsy or – in my favourite sketch – a parachutist in a wheelchair, dangling inches from the ground after getting stuck in a tree. Even better was The Last Leg, a nightly Paralympic round-up show hosted by one-legged comedian Adam Hills. "I had someone ask me, when I said I had an artificial right leg: 'Can you still have sex?'" Hills reported in the opening instalment "Yeah. What does your husband do? Take a run up?"

Suddenly C4 was back – going where other broadcasters daren't, giving voice to minorities, tackling diversity with wit and irreverence. The Last Leg was such a success that it is returning for a new series. Abraham says Hunt's dabs were all over the Paralympics coverage – surely a key piece of evidence in the case for her defence.

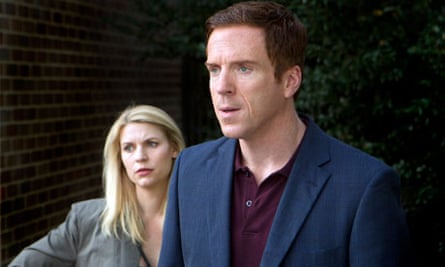

And other areas of C4's output are creditable. The purchase of US thriller Homeland shows that not all the best imports are being bought by Sky. Fresh Meat and Friday Night Dinner are good C4 commissions in an era when Sky, BBC3 and ITV2 have growing pretensions to broker the new funny. New animated sitcom Full English is getting enthusiastic notices. It has launched the conspiracy thriller Secret State starring Gabriel Byrne and given a TV premiere to Everyday, Michael Winterbottom's drama about a mother (Shirley Henderson) struggling with her family while her husband (John Simm) is in jail. Both should help to alter C4's recent reputation for selling TV drama short after a year in which only Top Boy and This is England have been significant counter-examples.

What's the case for Hunt's prosecution? One problem is that she was responsible for the car crash that was Hotel GB. At the show's launch in September, Hunt told the media that "Britain's first 10-star hotel", featuring C4's roster of celebs would be brilliant. Viewers (only 1.56m checked in on the first night) and critics thought otherwise. If that's the creative renewal Abraham says his channel is all about, we should worry.

While its competitors have been busy ploughing funds into scripted television – drama at ITV and the BBC, comedy at Sky – C4 invested in the obsolete celebrity reality show genre using contracted talent. "It's a failure of nerve as much as a failure of creativity," said one ex-C4 exec. "The reason Peep Show, The Inbetweeners and Misfits were such successes was that they started small and were allowed the chance to grow. Jay's not interested in that. She's all about the overnights [ratings]."

Another problem I heard repeatedly is that Hunt stifles her underlings' creative autonomy. "I find C4 impossible to deal with," said one head of an independent production company. "It's an unhappy ship of talented people who can't move anything forward as Jay Hunt micromanages everything."

But some of Hunt's failings are perhaps explicable because she's taken responsibility for C4 in recession and at a time when it lost its cash cow, Big Brother, to Channel 5. At Edinburgh she described that loss as equivalent to ITV losing Coronation Street. She hasn't yet found a new killer format to replace it, and the Hotel GB debacle suggests she might not be capable of creating it herself. Nor has she found replacements for long-running and increasingly tired franchises such as Grand Designs, Location Location Location or Super Nanny. She deserves a fair crack of the whip, though, a chance to turn things round.

"The cupboard wasn't exactly bare when I arrived and then Jay was hired, but there was a lot of work to do," says Abraham. If that sounds like Year Zero at C4 HQ, then it's perhaps unfair to cast him as Pol Pot and Hunt as his Kampuchean Nurse Ratched. Rather, Abraham suggests the channel is rediscovering what some thought it had lost for good – its soul. "There was a sense it had become almost a postmodern brand that did things without a sense of purpose." So what's his vision? "I like to think Channel 4 has a sense of mission and mischief combined." What does that mean? "I think that Channel 4 needs to go to uncomfortable places, but always with a purpose." Jeremy Isaacs could have said that in 1982 .

The worry, though, is that any discomfort C4 produces is motivated by headline-grabbing cynicism. For instance, when Make Bradford British was screened earlier in the year, much of the anger it attracted from West Yorkshire and beyond was over the racist presumption of its title; the programme itself, a fly-on-the-wall depicting cultural-clash angst, had the very purpose Abraham wants.

This isn't 1982. C4 now faces a cyberspace of alternative visions rather than three channels of competition. It often doesn't have deep enough pockets to buy up the classy imports and maverick talents that in days gone by would have been its birthright. It has creative chasms in its schedules that, Abraham insists (as he must), will be filled shortly with tip-top stuff. Today C4 struggles to secure ad revenue, but while Abraham's predecessors campaigned for state subsidy, he insists that the model of being an independently funded not-for-profit channel that cross-funds its less bankable but worthy programmes is necessary to retain its integrity. It's a business model that, however noble, would get him laughed off if he presented it on Dragons' Den.

This isn't 2007 either. Five years ago, the day my article criticising C4 appeared, their ex-head of press rang up to shout at me. How easy, he said, to slag off a media brand for its failings. "I could do the same number on the Guardian," he fumed. Fair point: no media outlet is responsible for unremitting marvellousness. It's easy to make the case for the prosecution. In reality, running a TV channel, even if you're only managing its decline, is more difficult.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion