Denis Mukwege: The rape surgeon of DR Congo

- Published

UPDATE 5 October 2018: Denis Mukwege has been jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work. This article was first published in 2013.

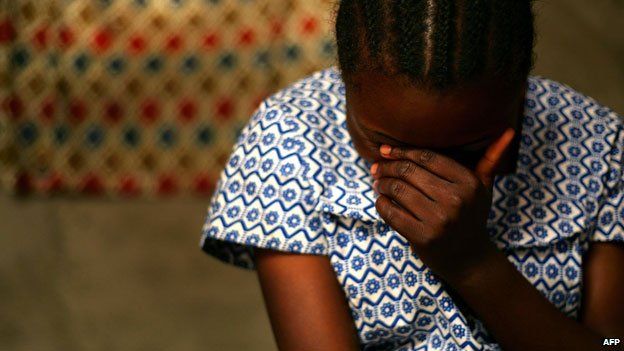

Denis Mukwege is a gynaecologist working in the Democratic Republic of Congo. He and his colleagues have treated about 30,000 rape victims, developing great expertise in the treatment of serious sexual injuries. His story includes disturbing accounts of rape as a weapon of war.

When war broke out, 35 patients in my hospital in Lemera in eastern DR Congo were killed in their beds.

I fled to Bukavu, 100km (60 miles) to the north, and started a hospital made from tents. I built a maternity ward with an operating theatre. In 1998, everything was destroyed again. So, I started all over again in 1999.

It was that year that our first rape victim was brought into the hospital. After being raped, bullets had been fired into her genitals and thighs.

I thought that was a barbaric act of war, but the real shock came three months later. Forty-five women came to us with the same story, they were all saying: "People came into my village and raped me, tortured me."

Other women came to us with burns. They said that after they had been raped chemicals had been poured on their genitals.

I started to ask myself what was going on. These weren't just violent acts of war, but part of a strategy. You had situations where multiple people were raped at the same time, publicly - a whole village might be raped during the night. In doing this, they hurt not just the victims but the whole community, which they force to watch.

The result of this strategy is that people are forced to flee their villages, abandon their fields, their resources, everything. It's very effective.

We have a staged system of care for victims. Before I undertake a big operation we start with a psychological examination. I need to know if they have enough resilience to withstand surgery.

Then we move to the next stage, which might consist of an operation or just medical care. And the following stage is socio-economic care - most of these patients arrive with nothing, no clothes even.

We have to feed them, we have to take care of them. After we discharge them they will be vulnerable again if they're not able to sustain their own lives. So we have to assist them on socio-economical level - for example through helping women develop new skills and putting girls back in school.

The fourth stage is to assist them on a legal level. Often the patients know who their assailants were and we have lawyers who help them bring their cases to court.

In 2011, we witnessed a fall in the number of cases. We thought perhaps we were approaching the end of the terrible situation for women in the Congo. But since last year, when the war resumed, cases have increased again. It's a phenomenon which is linked entirely to the war situation.

The conflict in DR Congo is not between groups of religious fanatics. Nor is it a conflict between states. This is a conflict caused by economic interests - and it is being waged by destroying Congolese women.

When I was coming home after a trip outside the country I found five people waiting for me. Four of them had AK-47 guns, the fifth had a pistol.

They opened the gate and got in my car, pointing their weapons at me. They got me out of my car and as one of my guards tried to rescue me they shot him down. He was killed.

I fell down and the attackers continued firing bullets. I can't really tell you how I survived.

Then they left in my car without taking anything else.

I found out afterwards that my two daughters and their cousin were at home. They had been made to go into the living room where the attackers were sitting, waiting for me. During all that time they pointed their guns, their weapons at my daughters. It was terrible.

I only saw the attackers for just a few seconds and I couldn't tell who these people were. I also can't say why they attacked me - only they know.

After the attack, Dr Mukwege fled with his family to Sweden, then to Brussels, but he was persuaded to return to Congo last month.

I was inspired to return by the determination of Congolese women to fight these atrocities.

These women have taken the courage to protest about my attack to the authorities. They even grouped together to pay for my ticket home - these are women who do not have anything, they live on less than a dollar a day.

After that gesture, I couldn't really say no. And also, I am myself determined to help fight these atrocities, this violence.

My life has had to change, since returning. I now live at the hospital and I take a number of security precautions, so I have lost some of my freedom.

When I was welcomed back by the women, they told me they would ensure my security by taking turns to guard me, with groups of 20 women volunteering in shifts, day and night.

They don't have any weapons - they don't have anything.

But it is a form of security to feel so close to the people you are working with. Their enthusiasm gives me the confidence to continue my work as usual.

Denis Mukwege spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service. Listen back to the interview via iplayer or browse the Outlook podcast archive.