Several years ago the Voyager spacecraft neared the edge of the Solar System, where the solar wind and magnetic field started to be influenced by the pressure from the interstellar medium that surrounds them. But the expected breakthrough to interstellar space appeared to be indefinitely put on hold; instead, the particles and magnetic field lines in the area seemed to be sending mixed signals about the Voyagers' escape. At today's meeting of the American Geophysical Union, scientists offered an explanation: the durable spacecraft ran into a region that nobody predicted.

The Voyager probes were sent on a grand tour of the outer planets over 35 years ago. After a series of staggeringly successful visits to the planets, the probes shot out beyond the most distant of them toward the edges of the Solar System. Scientists expected that as they neared the edge, we'd see the charge particles of the solar wind changing direction as the interstellar medium alters the direction of the Sun's magnetic field. But while some aspects of the Voyager's environment have changed, we've not seen any clear indication that it has left the Solar System. The solar wind actually seems to be grinding to a halt.

Today's announcement clarifies that the confusion was caused by the fact that nature didn't think much of physicists' expectations. Instead, there's an additional region near our Solar System's boundary that hadn't been predicted.

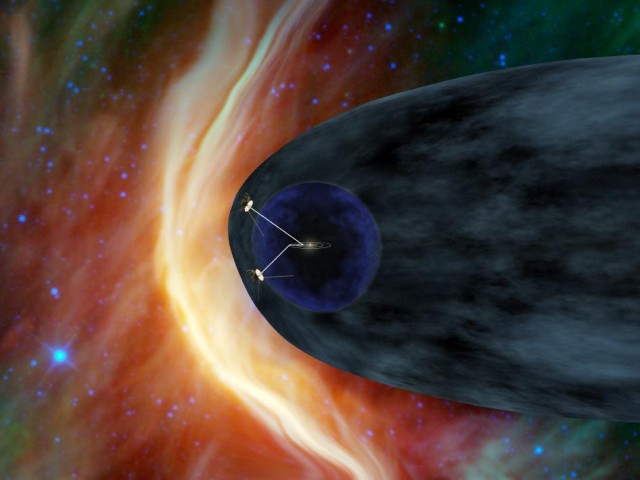

Within the Solar System, the environment is dominated by the solar magnetic field and a flow of charged particles sent out by the Sun (called the solar wind). Interstellar space has its own flow of particles in the form of low-energy cosmic rays, which the Sun's magnetic field deflects away from us. There's also an interstellar magnetic field with field lines oriented in different directions to our Sun's.

Researchers expected the Voyagers would reach a relatively clear boundary between the Solar System and interstellar space. The Sun's magnetic field would first shift directions, then be left behind and the interstellar one would be detected. At the same time, we'd see the loss of the solar wind and start seeing the first low-energy cosmic rays.

As expected, a few years back, the Voyagers reached a region where the interstellar medium forced the Sun's magnetic field lines to curve north. But the solar wind refused to follow suit. Instead of flowing north, the solar wind slowed to a halt while the cosmic rays were missing in action.

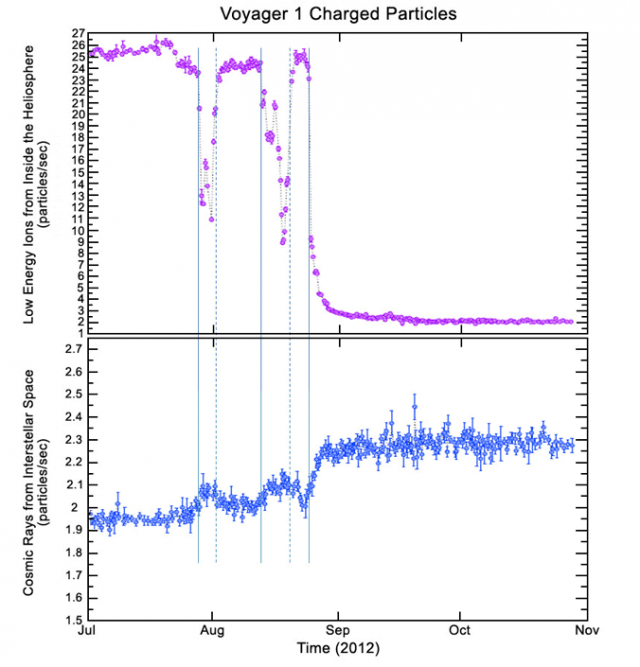

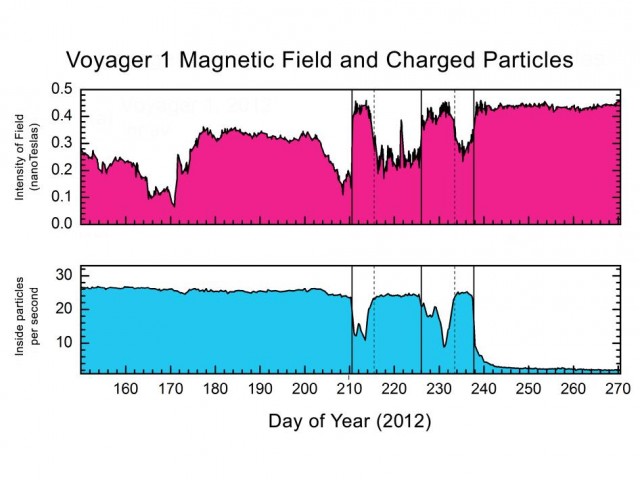

Over the summer, as Voyager 1 approached 122 astronomical units from the Sun, that started to change. Arik Posner of the Voyager team said that, starting in late July, Voyager 1 detected a sudden drop in the presence of particles from the solar wind, which went down by half. At the same time, the first low-energy cosmic rays filtered in. A few days later things returned to normal. A second drop occurred on August 15 and then, on August 28, things underwent a permanent shift. According to Tom Krimigis, particles originating from the Sun dropped by about 1,000-fold. Low-energy cosmic rays rose and stayed elevated.

That's a bit more expected; what wasn't expected is that the magnetic field of the Sun hasn't changed at the same time. Since it's been in the heliosheath, Voyager 1 has been seeing the magnetic field lines that originate from the southern hemisphere of the Sun. Those have been twisted around to face north by the pressure from the interstellar magnetic field. The orientation of these field lines hasn't changed at all, even as the particle counts shifted rapidly. In fact, the magnetic field lines appeared to get stronger and the increase in strength occurred in concert with the changes in particle counts.

The researchers suspect they've reached a region of the solar-interstellar boundary that nobody had predicted. In this area, the magnetic field lines of the Sun link up with those of the interstellar field. Scientists are calling this linkage a "highway" for particles to travel along. It lets solar wind particles escape more readily, causing the drop in their intensity. And it opens the door for low-energy cosmic rays to slip in to our Solar System, which is why Voyager 1 is seeing so many of them.

According the researchers at the press conference that announced these results, most steady-state models of the Solar System failed to predict anything like this. A few models did have a feature like this, but it was only a transient one that appeared at certain times of the solar cycle.

Voyager 2 is trailing behind and hasn't reached this region yet. Researchers suspect it may take several years for Voyager 1 to clear this area entirely, after which it will finally reach interstellar space.

reader comments

101