New Pope seeks to heal divisions in Latin America

- Published

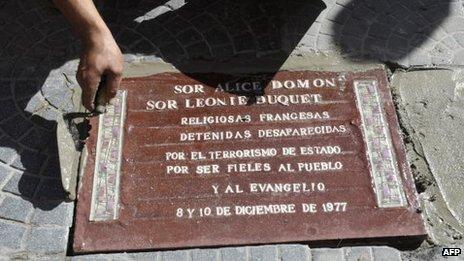

A small bronze plaque on the pavement of a central avenue in Buenos Aires marks the spot where two French nuns working in Argentina were snatched by the security forces in 1977.

The nuns, Leonie Duquet and Alice Domon, were never seen again.

Like many thousands of Argentines, they were "disappeared" during the military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1976 to 1983 - in their case apparently because they were working for the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo human rights group.

Many other priests and members of religious communities working with the poor or for human rights in Argentina suffered a similar fate.

Apology

At the same time, the Roman Catholic Church's local hierarchy - including the new Pope Francis, who at the time was head of the Society of Jesus of Argentina - were accused of not raising their voices in protest at the massive abuses being committed, or of not protecting the victims.

The Argentine military authorities, led by General Jorge Videla, regarded themselves as true Catholics. They even presented their repression as the fight between "Western, Christian values" and those of atheistic communism.

This view was apparently shared by many in authority in the Argentine Catholic Church at the time.

Not only were members of the junta welcomed at Mass, but several priests have since been convicted of involvement in murders and cases of torture at secret detention camps.

The then Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was accused of withdrawing the Jesuit order's protection of two priests who were working in slum areas of Buenos Aires in 1976. The two men were later picked up by the security forces, tortured, and imprisoned for five months.

Pope Francis has defended himself by saying that he worked behind the scenes on behalf of the families of the regime's victims. As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he was also instrumental in issuing a public apology by Argentina's Episcopal Conference for failing to stand against the generals during the "dirty war".

Liberation theology

The silence of the Argentine Catholic Church over the horrific human rights abuses during those years has been contrasted with the very different attitude of its Chilean counterpart.

During the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet between 1973 and 1990, the Archbishop of Santiago, Raul Silva Henriquez, was quick to set up the Vicaria de la Solidaridad (Vicarate of Solidarity), which played a far more positive role than the Church in Argentina in supporting relatives of political prisoners and torture victims.

The split between the conservative higher echelons of the Catholic Church in Latin America, and priests and religious orders determined to try to improve poor people's, can be traced back to the Conference of Latin American Bishops in Medellin, Colombia in 1968.

In the wake of Pope John XXIII's opening up of the Church with the Second Vatican Council in 1962, many in Latin America wanted to go further, and launched the idea of "liberation theology".

This put an emphasis on trying to fight the social inequalities which were particularly evident in Latin America, and spoke of committed clergy taking a "preferential option for the poor".

In countries such as Nicaragua, El Salvador and Colombia, this led to priests aligning themselves with left-wing revolutionary groups attempting to overthrow dictatorships or repressive regimes.

The authorities in Rome were always uneasy about liberation theology and any close involvement by members of the Catholic Church in political struggles.

During a visit in 1983 to Nicaragua, where the triumphant government of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) included several Catholic priests, Pope John Paul II publicly admonished Ernesto Cardenal for his role as a government minister.

In more recent years, both Gustavo Gutierrez in Peru, one of the founders of liberation theology, and Leonardo Boff, the outspoken Franciscan priest from Brazil have fallen foul of Rome.

Father Gutierrez, whose 1971 book A Theology of Liberation, helped launch the movement, was also criticised by Pope John Paul II and by the Catholic hierarchy in his own country.

Leonardo Boff was silenced for a year by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) for his book Church, Charisma and Power, which accused the Church hierarchy of abusing their authority and of being out of touch with ordinary Catholics.

Further attempts to restrain Fr Boff led to him leaving the priesthood in 1992.

'Subjects'

This tension between the two wings of the Catholic Church has greatly damaged its position in Latin America.

In Argentina, for example, although according to recent estimates some 90% of people regard themselves as Catholic, less than a quarter attend church regularly.

Evangelical Protestant churches, which have a less hierarchical structure and appeal more directly to poor people, have been making great inroads not only in Argentina but in many other countries in the region.

Pope Francis has said that the world's poor should not be seen as "objects", but as "subjects" for whom "state and society [must] create conditions that promote and protect their rights and allow them to build their own future".

Although the military regimes have now gone from Latin America, the new Pope will need great determination to ensure that the Catholic Church truly identifies with this aspiration.