French mourn Virgin's 'funeral march'

- Published

- comments

When it comes to the business of selling music, they do things differently in France.

From its humble beginnings on the UK High Street in the 1970s, Sir Richard Branson's Virgin record shop chain grew to become an international phenomenon.

At its height, it had stores throughout Europe and North America, as well as in Asia and the Arab world. But from the start of the 21st Century, the Virgin Group began selling off most of its music megastores to local companies.

This proved an astute move for Sir Richard. One by one, the newly spun-off operations began to go bust.

In 2007, the UK and Irish Virgin music and DVD shops were rebranded as Zavvi following a management buyout. But the chain later went into administration and closed its last stores in 2009.

That same year, Virgin megastores across the US shut their doors for good, as economic hard times and digital downloads took their toll.

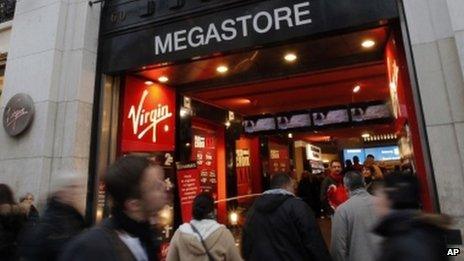

But somehow, through all this turmoil, Virgin carried on thriving as a music retailer in France, with a 4,500-sq m flagship outlet on the Champs Elysees in Paris and dozens of other shops elsewhere in the country.

Now changing times have finally caught up with Virgin France, as the prospect of insolvency looms. But while Anglo-Saxons saw the chain's demise as just one business failure among many, the French are viewing it as some kind of cultural apocalypse.

"Funeral march for megastores", screamed one headline this week in the left-wing newspaper Liberation. Underneath, the paper lamented the "merciless economic Darwinism" that has left Virgin and its rival Fnac unable to compete with Apple's iTunes digital music service.

'Unfair' competition

When the Zavvi group finally disappeared from the UK and Ireland in February 2009, it meant the loss of 125 stores and 2,300 jobs.

Despite this, the closures went ahead with no government intervention.

In the case of Virgin Megastores in France, the company has a smaller presence. Majority owned by the French investment company Butler Capital, it employs 1,000 people in 26 stores.

Even so, no-one seems to think it strange that the country's minister of culture, Aurelie Filippetti, should be having meetings with management and union representatives in an effort to keep the firm alive.

Without naming Apple or Amazon, Miss Filippetti complained in a radio interview about the emergence of big websites that "completely escape any kind of fair competition, because they don't pay the same taxes as the others, being based elsewhere than in France".

In other words, the decline of bricks-and-mortar shops selling music and books, which other countries view mainly in terms of technological change, acquires more than a tinge of economic nationalism in France.

Lurking behind all this is the fear that Virgin France and its bigger rival, the Fnac chain, will be wiped out by US multinationals who will come to dominate the French market.

By the book

So how did it come to this? And how likely is it that the fears of the French will be fulfilled?

Well, both Fnac and Virgin saw the digital wave coming. Since 2004, the Virginmega.fr website has been offering MP3s, followed by film and e-book downloads.

Fnac, which is the biggest bookseller in France as well as the biggest music chain, offers e-books and e-readers in partnership with the Kobo firm. But it closed down its Fnacmusic digital download service at the end of 2012, admitting that it was unable to win market share from iTunes.

Virgin, likewise, appears to have done too little, too late to keep up with changing times.

However, Fnac's greater share of the book trade may prevent its going the way of Virgin. Unlike CDs, books are not the same product everywhere in the world: they have to be translated into different languages.

A quarter of the US book market is now digital, but in France, only 2% of all books sold are e-books. And whereas Amazon can use deep discounts to sell physical books in other countries, another piece of French government action, introduced by former culture minister Jack Lang, fixes the price of books and severely limits discounting.

Nonetheless, the French seem unconvinced that their cultural champions can play the game of market forces and win. There are already calls for the French state to follow its instincts and intervene, in the interest of creating a more level playing field.

Liberation, for one, is denouncing what it sees as "unfair competition, founded on fiscal dumping".

Its editorial concludes: "The phenomenal power of the digital revolution does not exclude regulation: it requires it."