Large galaxies such as the Milky Way have many smaller satellite galaxies, bound to them by gravitation. According to the widely accepted theories of galaxy formation, these satellites were leftovers from the slow merger process that made the larger galaxies. We'd expected these satellite galaxies to be evenly distributed around the Milky way, but recent studies showed that many of them lie close to a single plane, tilted with respect to the Milky Way's disk. New observations may have revealed a similar structure of satellites around our closest large neighbor M31, also known as the Andromeda Galaxy.

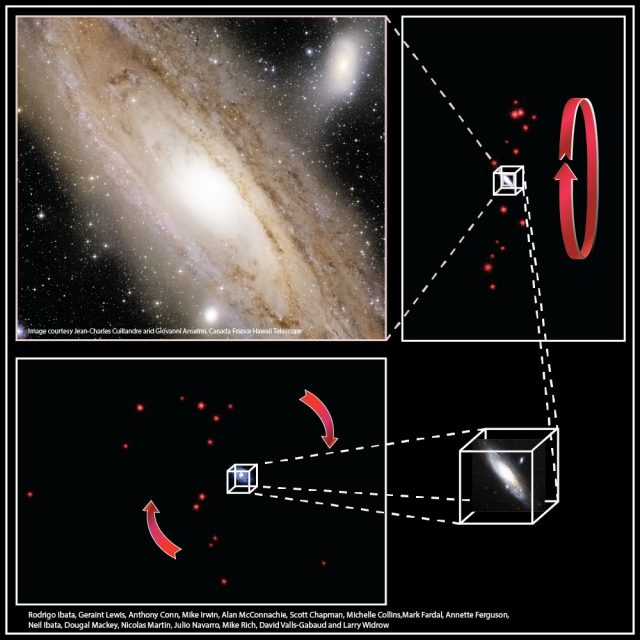

Rodrigo A. Ibata and colleagues found that nearly half of M31's known satellites lie in a single, relatively thin plane. They also measured the motion of these galaxies and found they were revolving in the same direction around Andromeda. These results—as with the previous Milky Way observations—were contrary to expectations, in which satellites would be distributed more or less spherically and moving in random directions.

A complete census of Milky Way satellites is difficult to achieve. Since we are located within the Milky Way's disk, a large part of the sky is obscured by our own galaxy, which may block the view of several small galaxies. While a few examples of the satellite galaxies are large—the Magellanic Clouds for the Milky Way and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) for Andromeda—most are small and faint, increasing the challenge of locating them all.

The Pan-Andromeda Archaeological Survey (featuring the diverting acronym PAndAS) was established to provide a high-resolution, large-scale panorama of M31 and its environs. 27 dwarf galaxies that can be unambiguously associated with Andromedalie within the PAndAS survey region. The astronomers measured the distances and velocities of each of these galaxies, yielding a three-dimensional and dynamical view of the M31 system.

They found 15 of those satellites were arranged along a relatively thin arc from the perspective of Earth, meaning they lie close to a single plane. Further analysis revealed 13 of the 15 galaxies were also moving in a coherent pattern: those "north" of Andromeda were moving away from us, while those "south" were traveling toward us. That indicates a clear rotational pattern; the authors estimated only a 1.4 percent probability of motion like this being random chance.

As with most things in galactic astronomy, the dynamics are somewhat messy. The disk is relatively thin compared to a sphere surrounding M31, but it's still 46,000 light-years thick—nearly 15 times thicker than Andromeda's galactic disk. Nevertheless, the structure appears real: it's extremely improbable that galaxies would arrange themselves in such a fashion under the ordinary action of gravity.

According to the theory of structure formation, galaxies collapsed gravitationally in roughly spherical shapes, with rotation in large spiral galaxies producing the flat disk structures. Satellite galaxy motion would be random, since they form independently of each other before coming close enough to be captured via gravity. The standard versions of galaxy formation—along with modified gravity schemes—are currently unable to explain flat, rotating structures composed of dwarf galaxies. It is possible that these satellites must have formed together in some way, since they are all relatively ancient (based on the populations of stars they contain).

But there is an alternate possibility, given that the disk of galaxies is nearly aligned with the Milky Way. While the authors are (wisely) reticent to guess why that might be, the alignment suggests the possibility that the two biggest galaxies in the Local Group (the structure containing M31, the Milky Way, and a number of other much smaller galaxies) affected the formation or orientation of each others' satellites. Assuming the alignment isn't coincidental, it's possible that this idea can be formulated as a coherent physical model. Not all of M31's satellites are part of the structure, though, so things remain (as the kids say) complicated.

Another caveat: we only have extensive satellite galaxy data on M31 and the Milky Way, but there are 100 billion large galaxies in the observable Universe. Without further data, there is no way to determine whether disk-like structures are common or not. Nevertheless, their presence in both Andromeda and the Milky Way hint that they may be present elsewhere. Further work is necessary, both on the theoretical and observational sides, to resolve the questions these findings raise.

Nature, 2012. DOI: 10.1038/nature11717 (About DOIs).

reader comments

41