Eerie Rock Towers Are Earthquake Sensors

Strange rock formations in the California desert provide clues to the strength of past earthquakes, a new study suggests.

In Red Rock Canyon, about 120 miles (190 kilometers) north of Los Angeles, tall, rusty spires of rock called hoodoos dot the landscape. The otherworldly spindles form in sedimentary rock, where harder layers protect softer layers below. Erosion wears away the less-resistant rock, leaving thin caps or even large boulders of harder rock perched on soft towers. This being California, Red Rock Canyon has served as a backdrop for more than 100 movies, from classic westerns to the opening scenes of "Jurassic Park."

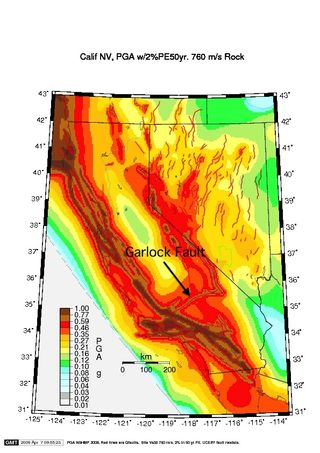

California's second largest strike-slip fault, the Garlock Fault, passes just 3 miles (5 km) north of Red Rock Canyon's fragile hoodoos. (A strike-slip fault is a fracture where the earth on either side slides mostly parallel to the fault.) About 500 years ago, a strong earthquake, estimated at about magnitude 7.5, struck on a segment of the Garlock Fault nearest Red Rock Canyon.

The canyon's hoodoos are evidence the region near Red Rock Canyon did not undergo strong shaking during the earthquake, according to a study published today (Feb. 4) in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. That's good news for nearby cities such as Palmdale, home to Edwards Air Force Base.

"The fact that they didn't break indicates the ground motion was lower than you might expect," said Abdolrasool Anooshehpoor, a geophysicist with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The research was conducted while Anooshehpoor was a professor at the University of Nevada, Reno.

A caveat

The researchers relied on one big assumption in determining how the past quake affected the weird rocks: that the hoodoos look pretty much the same as they did 500 years ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a big uncertainty," Anooshehpoor said. They have no estimates of how fast the hoodoos form, or of how long the rock has been exposed at the surface. "Basically, we assume in the past 500 years, in time since this earthquake happened, the shape has not changed much."

Anooshehpoor and his colleagues at the University of Nevada, Reno, have a long-standing interest in precariously balanced rocks, or PBRs — massive granite boulders poised like a child's top. In Southern California, the presence of PBRs is thought to be evidence an area has not experienced strong, earthquake-induced shaking since the rocks formed.

But the desert near the Garlock Fault lacks the granite outcrops that form PBRs, so the researchers looked for another way to gauge shaking. "I don't want to say hoodoos are a last resort, but because of their nature, you have to be very careful when you use them. They are very fast-eroding," Anooshehpoor told OurAmazingPlanet.

Small shaking

They picked two of the most fragile-looking hoodoo in Red Rock Canyon and scanned their shapes. A rock sample brought back to the lab and crushed with a piston provided data on the tower's strength. Computer modeling revealed the ground acceleration, or shaking, required to break the hoodoos. [Video: Scary Scenario: Devastating Earthquake Visualized]

The upper limit on shaking offered by the most fragile hoodoo matches the 2008 U.S Geological Survey seismic hazard maps for the region, Anooshehpoor said. Seismic hazard maps predict the peak ground acceleration, or shaking, expected from future earthquakes. They are based on earthquake history and how fast a fault moves, or slips.

Geologist David Haddad of Arizona State University, who was not involved in the study, said hoodoos and other precariously balanced rock features can provide important constraints on ground motion from earthquakes. "I think they did a good study," he said. "They're basically validating the 2008 seismic hazard map for California."

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.