Playwright and screenwriter Tony Kushner remembers his friend Maurice Sendak

One morning several years ago, Lynn Caponera, Maurice Sendak's longtime assistant, housekeeper and best-beloved friend arrived at his home to find him sitting on the sofa in the living room, a place in the house where he seldom spent much time. Lynn asked him what he was doing in there. He told her that the night before, he'd been awakened in his bedroom above by the sound of something repeatedly striking a window. He went downstairs and discovered a bat sitting on the sofa.

Maurice sat down beside the bat, which began to speak to him in German. It went on and on, but he couldn't understand much of what the bat was saying because Maurice's grasp of German was poor. When it finally paused, Maurice asked the bat what it was talking about. It said that it had been telling him how much it loved him.

Maurice asked Lynn, "Do you believe me?"

"Yes," she replied, "somehow I do."

When Maurice asked Lynn if she believed him, was he, I wondered, asking her if she believed he'd had a nocturnal conversation with a bat? Or was he asking if she believed what was implicit in the story he was telling? Did she believe that this was how he felt love reached him: in the lonely night, in a rarely visited room, in a serenade from a chattily familiar and yet alien creature fluttered up from the cave of the unconscious, in the nearly incomprehensible, enticing, forbidden language of Mozart, Mahler and the Holocaust – and also in the language of Freud, heart's truth spoken from a couch? Was Maurice asking Lynn if she loved him, which meant that she believed enough to surrender incredulity, to step with him out of reality, into a realm of the imaginary in which, at last, he could be understood? Did she, in other words, truly believe in the august imagination? Did she believe in art?

Any seasoned visitor to the World of Sendak was accustomed to hearing its resident magician relate extraordinary events with such fluency, gravity and fervency that unless the story involved a German-speaking bat, its mere improbability never seemed a reliable standard by which to assess whether or not it had actually happened – or whether, as in the case of the bat, Maurice believed it had.

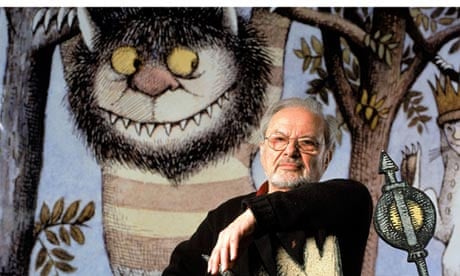

He and I were friends for 20 years, and I miss him terribly. His books will last as long as there are people on the planet, but he's gone, and he's taken with him the irreplaceable pleasure – the unique amalgamation of delightful nuttiness, naked, unapologetic need, wild associations and prodigious, profligate spontaneous invention – that could be had in his company.

In 1993, he read an interview I'd given in which I'd said that my favourite American author was Herman Melville. Since he felt the same about Melville, Maurice decided we should meet, not realising that another American author I passionately admired was Maurice Sendak. Other than Lewis Carroll, no author I read as a child meant as much to me. I continued to read Maurice's books as an adult, compelled to follow the steady stream of his work because, unlike the other key figures in the postwar revolution in children's literature, Maurice grew as an artist, and his work constantly changed. Alone among his peers, he was possessed by a searching, ambitious restlessness that wouldn't permit him to settle comfortably into a style.

Maurice was never interested in supplying children with momentary distractions or reliable soporifics; he wanted to make rich, complex, even dangerous art for them. He risked everything and dared anything, even failure, to uncover truth. He pushed at the boundaries of his form to expand its expressive capabilities, its capacity for generating meaning. He was protean, and over the years, his books became stranger, darker, more complex and more magnificent. He was a very serious artist. With a depth of feeling and intensity that might seem odd in an author and illustrator of children's books, Maurice believed in art.

In a few months, My Brother's Book, Maurice's last complete work will be published. It was written and drawn with heroic effort as, at 83, he battled hand tremors and cataracts, grief over the death of Eugene Glynn, his partner of 50 years, and the deaths of many friends. The book is rough, surprising, and entirely new. It's intended for us, the adults Maurice helped to create by making the books he made.

His grateful readers and adoring friends loved him because he told us the truth; he warned us, in book after book, that death divides the living from the loved, and also, impossibly, that love lasts even when life doesn't. Do we believe him? Somehow, through some potent magic he possessed, we do.

Read the Guardian obituary here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion