Deepest Corals in Great Barrier Reef Discovered

Updated on Jan. 3 at 7:18 p.m. ET.

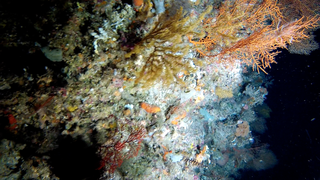

Even four times as deep as most scuba divers venture, the Great Barrier Reef blooms. A new exploration by a remote-operated submersible has found the reef's deepest coral yet.

The coral Leptoseris is living 410 feet (125 meters) below the ocean's surface, a discovery that expedition leader Pim Bongaerts of the University of Queensland called "mind-blowing."

Coral reefs are made of colonies of polyps which secret a rock-like exoskeleton. The polyps have a symbiotic relationship with algae that provide them nutrients using photosynthesis. Because this process requires light, coral reefs thrive in clear, relatively shallow water.

"The discovery shows that there are coral communities on the Great Barrier Reef existing at considerably greater depths than we could have ever imagined," Bongaerts said in a statement.

Coral colonies

The 410-foot distance is surprising for the Great Barrier Reef, where scuba divers find stunning coral displays at depths down to 100 feet. But corals are known to live deep elsewhere. In the Gulf of Mexico, researchers have found the coral Lophelia pertusa thriving 2,620 feet (799 m) down. Lophelia doesn't need sunlight to survive. In Puerto Rico, light-dependent corals survive as far down as 500 feet (150 m).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bongaerts and his colleagues received funding from insurer the Catlin Group Limited to explore the Great Barrier Reef as part of an effort to understand how climate change is altering the oceans.

On the outer edge of the Ribbon Reefs, off the northern Great Barrier Reef, the researchers hit unusually calm seas and were able to deploy a remote-operated vehicle, or ROV, off the edge of the Australian continental shelf, where the ocean floor plummets hundreds of feet. It was a tough dive, said expedition member Paul Muir, a taxonomist from the Museum of Tropical Queensland. [See Photos of the Deep Reef Corals]

"With more than 250 meters of cable out to provide power and communications with the ROV, it was a real struggle to collect a specimen of one of these corals," Muir said in a statement.

The deep reef

The team persevered and brought one precious Leptoseris coral sample back to sea level. Typically, such corals peter out in the Great Barrier Reef above 330 feet (100 m), replaced by non-light-dependent sponges and sea fans. Using the ROV, the team also found the deepest Staghorn Acropora, a type of coral that makes up the majority of most of the world's reefs.

"These discoveries show just how little we really know about the reef and how much more is yet to be discovered," Bongaerts said. "This poses lots of questions for us, but now we have specimens, we'll be able to analyze them much more closely and can expect our findings to reveal a far greater understanding of just what is going on to enable reef corals to survive at such extreme depths."

The Great Barrier Reef has been in decline, with half of it vanishing in the last 27 years, according to a study released in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last October. Climate change is boosting the temperature of the oceans, causing some of the damage. Another reef foe is the crown-of-thorns starfish, which eats coral. The starfish populations have exploded because of nutrient runoff from agricultural fertilizers.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct the name of Leptoseris.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.