And that's it from me. Thanks for all the comments.

Skeleton found in car park is that of Richard III – as it happened

Read a summary of what the academics discovered

Read more: DNA confirms twisted bones belong to king

Live feed

Summary

Here's Maev Kennedy's full news story on today's announcement, and here is a summary of what we’ve learned.

Tests have established that a skeleton found under a car park in Leicester is that of Richard III, king of England from 1483-85. Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist on the project at the University of Leicester, said that his team had proved “beyond reasonable doubt” that the bones were those of the last Plantagenet king.

DNA evidence from the skeleton matches with that from Michael Ibsen, a Canadian who is a direct descendent of Richard’s sister Anne of York. In addition, evidence of battle wounds on the skeleton, and features of the remains such as their curved spine, provide a “highly convincing case” for this being Richard, Leicester’s Dr Jo Appleby said.

His death was probably caused by one of two injuries to the base of the skull, both inflicted with a bladed weapon, Appleby said.

My colleague Patrick Barkham has produced this run-down of things to do and see in Leicester, which is now set to become one of the UK's top tourist hotspots.

My colleague Maev Kennedy has been speaking to Michael Ibsen, the Canadian-born furniture maker now proved as the descendant of Richard’s sister. Ibsen heard the confirmation on Sunday and listened to the unfolding evidence in shocked silence. He told Maev:

My head is no clearer now than when I first heard the news. Many, many hundreds of people died on that field that day. He was a king, but just one of the dead. He lived in very violent times, and these deaths would not have been pretty or quick.

Mathew Morris, who first uncovered the body, in the first hour of the first day of excavating the site, told Maev:

I’m a medievalist really. I don’t go much for the Tudors. Even if Richard did kill the princes in the tower, you have to judge him by the standards of his day – no other medieval king would have taken the risk of leaving them alive.

The story of the princes in the tower was infamous even in Richard’s day, as Maev reports: “the child Edward V and his brother Richard, declared illegitimate when Richard III claimed the throne, imprisoned in the tower of London and never seen alive again.”

Work has already begun on designing a new tomb in the cathedral, only 100 yards from the excavation site, Maev reports, and Canon David Monteith said a solemn multi-faith ceremony would be held to lay him into his new grave there, probably next year.

Maev Kennedy sends this picture of a subdued Michael Ibsen, descendent of Richard III's sister Anne of York, saddened by the account of the king's fearsome death.

My colleague Charlotte Higgins seems to share some of Mary Beard's scepticism about the value of today's discovery, and disquiet about the way it was announced.

I'm not saying it's not good fun, and indeed mildly interesting, that the remains of the last Plantagenet king have apparently been found. (We should note that the bone evidence is clearly circumstantial – a skeleton with curvature of the spine and battle injuries does not a king make, though I can't claim to know enough about DNA evidence to understand what the margin of error is here, particularly before the findings have been published in a peer-reviewed journal rather than just announced in a press conference.)

I'm just suggesting that it's rather a limited avenue of historical research that seems to have much to do with the dread word "impact" – in which academics are supposed to show that their work has "real-world" effects, whatever that might mean, though often interpreted to include public recognition and media coverage. The affair as a whole – notwithstanding the undoubted integrity, skill and commitment of the individuals at work – seems to me to have been managed in a way that is more about fulfilling the dead-eyed needs of the Research Excellence Framework (the highly contentious new scheme for assessing university research) than with pursuing a genuinely intellectual field of enquiry ...

Watching the press conference on TV, I'm afraid (even though it was designed for attendance for people just like me) give me the chills. Yes, it raises awareness of the University of Leicester. Yes, it shows people the work of archaeologists and other experts, and draw interested people in to the discipline (not least potential students). Yes, no doubt it will help the department secure funding (which is surely what all the jamboree was about, in the end). All of that is fine. But it's not really history, not in any meaningful sense.

Historian Helen Castor, an expert on the 15th century, tells the Guardian she thinks the find is significant:

For what it's worth, I think it's an extraordinary story of archaeological detective work to have found the body, and the anatomical analysis will mean we now have some facts with which to calibrate our reading of both contemporary evidence and Tudor propaganda about Richard's appearance, and the accounts of his death at Bosworth. So in those senses [it is] significant.

Summary

Here is a summary of what we’ve learned this morning.

Tests have established that a skeleton found under a car park in Leicester is that of Richard III, king of England from 1483-85. Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist on the project at the University of Leicester, said that his team had proved “beyond reasonable doubt” that the bones were those of the last Plantagenet king.

DNA evidence from the skeleton matches with that from Michael Ibsen, a Canadian who is a direct descendent of Richard’s sister Anne of York. In addition, evidence of battle wounds on the skeleton, and features of the remains such as their curved spine, provide a “highly convincing case” for this being Richard, Leicester’s Dr Jo Appleby said.

His death was probably caused by one of two injuries to the base of the skull, both inflicted with a bladed weapon, Appleby said.

Richard’s body will be reinterred in Leicester Cathedral, probably early next year. A temporary exhibition will open there on 8 February, followed by a permanent visitors’ centre telling the story of Richard’s life and death. A £10,000 donation for a new tomb for the monarch has already been received by the Richard III Society.

Louice Tapper Jansson sends these amusing tweets:

As Jon @bbc6morningshow just pointed out, the battle *was* nearby, so that's obviously where he would have parked. #RichardIII

— Lauren Laverne (@laurenlaverne) February 4, 2013

The daily rate for an Leicester NCP car park is £18.50. #RichardIII has been there 192,649 days. He owes £3,564,006.50 in parking fees.

— Jonny Durgan (@JonnyDurgan) February 4, 2013

To be honest, finding Trevor Jordache under the patio was more exciting. #richardiii

— Ryan Kent (@ryankent) February 4, 2013

I read it as Richard ill. Imagine my disappointment to find that he is actually dead. #richardiii

— Alan Davis (@f5f5f5) February 4, 2013

Broadcaster Dan Snow is also weighing in on Twitter:

David Cameron must sympathise with the mutilated Richard III; both are leaders who have dealt with catastrophic defections.

— Dan Snow (@thehistoryguy) February 4, 2013

Does #RichardIII corpsegate matter? Not much. Is it exciting? Very.

— Dan Snow (@thehistoryguy) February 4, 2013

I missed one rather graphic detail from Dr Jo Appleby's discussion of the wounds found on Richard's body. Maev Kennedy summarises it succintly:

Stab through right buttock after death consistent with humiliation of his naked dead body while it was slungover pommel of horse

— Maev Kennedy (@maevesther) February 4, 2013

Cambridge academic and TV star Mary Beard is uncomfortable with the way the University of Leicester hyped up the discovery of Richard's remains.

Gt fun & a mystery solved that we've found Richard 3. But does it have any HISTORICAL significance? (Uni of Leics overpromoting itself?))

— mary beard (@wmarybeard) February 4, 2013

@traxdollhead Hope not sour grapes... but the logos all over the place are a bit de trop, methinks. Great fun, but what's the History here.

— mary beard (@wmarybeard) February 4, 2013

@katieharker dont think I'm bitter. Want to see WHY its historically significant. Some tweets HAVE suggested reasons. not mentioned on tv.

— mary beard (@wmarybeard) February 4, 2013

@debmarson Sure.. & I think it nice to have him. But still dont think that it give much new history (which is usually much less glam).

— mary beard (@wmarybeard) February 4, 2013

My colleague Paddy Allen has created this excellent interactive graphic of the site where the remains were found.

A £10,000 donation for a new tomb for Richard has already been received by the Richard III Society, Maev Kennedy reports.

Sir Peter Soulsby, the mayor of Leicester, confirms that the king's body will be reinterred in Leicester Cathedral.

He says he has written to the acting dean of the cathedral formally entrusting the remains to the cathedral.

From 8 February there will be a temporary exhibition there, and a permanent visitors' centre will be opening next year, telling the story of Richard's life and death. He hopes that will be open at a time to coincide with the reinterment, which will take place early next year, he thought.

Richard Taylor returns to say that reinterment will be in Leicester Cathedral.

Whoops and cheers follow the announcement.

It's Richard III

Richard Buckley returns to announce the team's conclusion.

He says that it is their academic view that "beyond reasonable doubt the individual exhumed at Grey Friars on September 12th is indeed Richard III, the last Plantagenet king of England".

Geneticist Dr Turi King says both the individuals who helped with the DNA analysis – Michael Ibsen and another person who has asked to remain anonymous – are "the last of their line" – so in a generation comparing DNA in this way would not have been possible.

DNA analysis of the remains was difficult, but they did manage to get a sample of DNA to work with.

The DNA confirms this is a male.

She shows part of Michael Ibsen's DNA sequence, which verified the family tree Schürer set out.

There is a DNA match from the descendents of Richard III and the skeleton at Grey Friars.

The DNA evidence points to these being the remains of Richard III, she says.

Prof Lin Foxhall speaks next, saying we may now have to re-evaluate what we know about Richard III's life.

Prof Kevin Schürer then says the team can confirm the lineage from Anne of York to Michael Ibsen is good.

Skeletal evidence provides 'highly convincing case' that this is Richard III

Dr Jo Appleby has said the evidence from the skeleton provides a "highly convincing case" for this being Richard III.

Taken as a whole, the skeletal evidence provides a highly convincing case for this being Richard III, Appleby says in conclusion.

BREAKING! World first - The complete skeleton showing the curve of the spine #RichardIII ow.ly/i/1t0gN

— Uni of Leicester (@uniofleicester) February 4, 2013

There is also a small, rectangular injury on the cheekbone, consistent with a dagger.

And there is a cut mark on the lower jaw, caused by a bladed weapon, Appleby says.

It is hard to understand how any of these injuries could have taken place if he was wearing a helmet, she says. He may have lost the helmet at this time, or some of the injuries could have been caused straight after death.

Appleby discusses the wounds. Ten have been identified, eight on the skull. They all occurred at the time of death or shortly after.

None overlapped so it was not possible to say for certain the order in which they were received, she says.

There was a small, penetrating wound on the top of the head. This came from a direct blow from a weapon, and would not have been fatal.

A large wound to the base of the skull came from a slice cut off the skull by a bladed weapon. A smaller injury on the base of the skull was also caused by a bladed weapon. Both of these injuries would have caused almost instant loss of consciousness and death would have followed shortly afterwards.

There are also three more shallow wounds on the skull.

Dr Jo Appleby speaks next.

She says the team had to answer whether the skeleton fitted with the known facts about Richard, and examine the spinal curvature and the wounds.

Appleby says the skull was struck during excavation but this did not cause major damage. There is also damage to the bones from their being buried for 500 years.

It was an adult male but with an unusually slender, feminine build. That's consistent with descriptions of Richard.

There is no indication he had a withered arm, however.

He was aged in his late 20s to late 30s. That fits with Richard's age when he died.

The skeleton was not born with scoliosis, she says.

Buckley says the skeleton can be dated from 1455-1540.

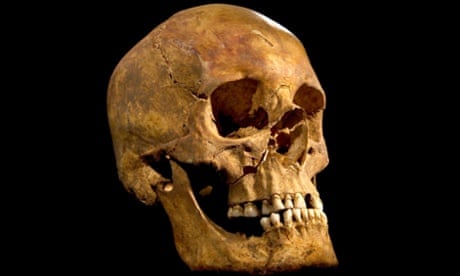

Buckley shows an image of the grave and an image of the skeleton. He says the hands may have been tied at the time of burial.

Buckley calls the body in this burial site "skeleton one".

Skeleton one exhibited certain "interesting characteristics": curvature of the spine and trauma to the head.

Buckley says a third trench was opened in an adjacent car park. This revealed a pair of walls.

So now they were confident the burial found in the first trench lay within the church.

Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist, speaks next.

He says no information about the Grey Friars buildings have survived.

The precinct is now crossed by two streets and extensively built over - so finding it would always be a long shot, he says.

Buckley says he chose to investigate two trenches in the social services car park there.

The team discovered evidence of a burial in the first trench almost immediately.

In the second trench they seemed to find parts of the church.

Taylor says that following the dissolution of the monasteries, the trail goes cold. Popular legend has it that an angry mob threw his remains in the river.

He invites the team to present their evidence.

Richard Taylor, deputy registrar of the University of Leicester, says what they are about to say is "truly astonishing".

In August 1485, Richard III faced Henry Tudor at Bosworth and was killed. His body was brought back to Leicester. His body was buried without pomp or ceremony in the church of the Grey Friars.

Professor Sir Robert Burgess, vice-chancellor of the University of Leicester, is speaking.

Milking the moment a bit, Burgess says only the researchers can tell us whether the remains are those of Richard III.

The press conference is just beginning now.

Professor Sarah Hainsworth of the engineering department has been working on microtomography imaging of the skeleton, Maev reports. It has two injuries to the base of the skull, one to the crown (not that crown), and more to the ribs and pelvis. "He had literally been through the wars," Maev notes.

A bit of a clue courtesy of Maev Kennedy in Leicester: Sarah Levitt, head of Leicester museums, says they'll be opening a display at the Guildhall in a week - and a whole new visitor centre in the old Alderman Newton school, right by the excavation site, next year.

Maev Kennedy has just been speaking to Phil Stone, the chair of the Richard III Society, which funded the search for his remains. Stone calls this "a very exciting day". The thrill of the chase has more than doubled membership to 3,000, he says. They have nothing to do with the Tudors, "but we do meet the Stuarts every now and then, at Fotheringay and such".

The University of Leicester has provided TritonE recorder players to soothe journalists' savage breasts, Maev Kennedy reports. They have also rerecorded all Radio Leicester's jingles and idents in Plantagenet style for today.

The hall is filling up fast, says Maev, who sends this picture of Bob Savage of the Royal Armouries, whose expertise on medieval war injuries could be crucial.

Good morning. At around 10am today, researchers are due to announce whether a skeleton found underneath a car park in Leicester is that of Richard III. We’ll have live coverage here as they reveal whether the bones really are the remains of the last Plantagenet king of England, who died at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

We’ll be hearing from my colleague Maev Kennedy, who is in Leicester and wrote this excellent summary of where we stand for today’s Guardian.

The University of Leicester, which has been leading the project, is refusing to speculate on what the result will be. But archaeologists, historians and local tourism officials are all hoping for confirmation that Richard’s long-lost remains have been found. The university has released an image of the skull, which archaeologist Jo Appleby said was “in good condition, although fragile”.

Since the discovery, researchers have been conducting scientific tests on the remains, including radiocarbon dating to determine their age. They have also compared its DNA with samples taken from Michael Ibsen, a Canadian believed to be a direct descendant of Richard’s sister Anne.

Lynda Pidgeon of the Richard III Society told the Associated Press:

It will be a whole new era for Richard III. It's certainly going to spark a lot more interest. Hopefully people will have a more open mind toward Richard … With Henry VIII you've got six wives, sex and things going on. It's a bit hard to compete with that when you are a bit more straight-laced, as Richard was.

Richard III ruled England from 1483-85, during the Wars of the Roses, and was defeated at Bosworth Field by the army of Henry Tudor, who took the throne as Henry VII. He was the last of the Plantagenet dynasty to rule, and was immortalised in one of Shakespeare’s history plays.

The location of his body has been unknown for centuries. As Maev writes: “Although stories say his body was dumped in the river, many believe the body was claimed by the Franciscans and buried hastily but in a position of honour near the high altar of their church – exactly where the remains were found.”

Last September archaeologists looking for Richard dug up the skeleton of an adult male who appeared to have died in battle. He appears to have a battle wound in the skull and a barber metal arrowhead was found between vertebrae in his upper back. The skeleton also displays signs of curvature of the spine, which is consistent with contemporary accounts of Richard III’s appearance. (Shakespeare added the famous hunchback.)

Stay tuned for live coverage of the announcement from 10am.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion