Why South Africa is like a Mexican soap opera

- Published

- comments

With the African National Congress party's figurehead Nelson Mandela in fragile health and the country facing a series of difficult problems, this is a critical period for South Africa.

It was late afternoon, and they were still cheering. Every few seconds another name was read out, and the families - some overflowing into the lobby outside the hall - jumped up from their chairs with delight.

It was graduation day at Johannesburg's grand, elegant Wits University this week.

I sat on the steps outside the hall, soaking up the noisy waves of optimism that kept rushing past.

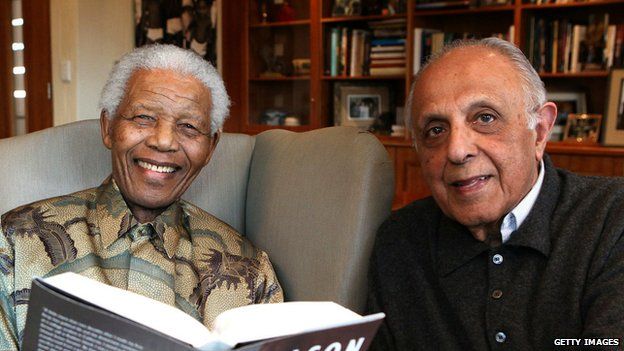

Inside, Ahmed Kathrada seemed to be doing much the same. He is 83 years old now, and a little frail but still very much the same rigorous intellectual heavyweight who spent quarter of a century in prison with Nelson Mandela.

Mr Kathrada was at Wits to receive his own honorary doctorate. Afterwards, away from the well-dressed crowds streaming out of the hall, he sat down carefully, smiled, and said: "A day like this makes you feel good about this country."

Of course, we then started talking about everything that was going wrong - about the prevailing sense of gloom, even crisis, that has settled on South Africa.

"I just wish we could unite," he said solemnly, "as we used to in prison, to fight a common enemy".

It has been a rough few months here: The killing of 34 workers at the Marikana mine; the corruption and chaos exposed almost daily within the ruling ANC; the downgrading of South Africa's economic prospects by ratings agencies.

Grim stuff. But it is worth remembering that crisis is something of a speciality here.

Nonsense

If South Africa were a television show, it would probably be a Mexican soap opera - raucous, full of absurd, repetitive plots, with the promise of imminent disaster and salvation around every corner.

It is as if the nation cannot quite let go of its genuinely miraculous, dramatic past and accept the fact that it has become just another messy, complicated country.

Of course, this week we have all been reminded of that past with the news that Nelson Mandela, now 94 years old, is back in hospital.

Over time most South Africans have quietly come to accept the fact that he will not be here forever.

But it is striking how many people seem genuinely worried about what will happen when he is gone.

It used to be a few shrill, nervous white people who talked about how it was only Mr Mandela - with his moral authority - who was preventing the black majority from throwing them out of the country or worse. But now you hear black people worrying about what will happen too.

I spent an hour recently, arguing with a bright student who was convinced that civil war was inevitable.

Such fears are, I am sure, nonsense. In political terms South Africa has already been living in a post-Mandela era for longer than it would like to admit.

But the ruling party - the ANC - still leans heavily on its liberation history, and on Mr Mandela in particular, and it does have a lot to lose.

Fractious nation

This weekend the ANC is gathering, as it does every five years, to decide who should lead the party and which policies it should champion.

The run-up has been quite a spectacle. You could argue that the furious power battles are a sign of healthy internal democracy, or you could look at the political murders, and the greedy factionalism as proof that yet another African liberation movement has pressed the self-destruct button.

It is worth mentioning that the ANC, for all its flaws, has plenty of good people - and achievements - under its belt.

And it can adapt. After the disastrous HIV/Aids denial of the past, President Jacob Zuma's government has rolled out the right drugs, and life expectancy for South Africans has jumped from 54 to 60 in five years. A spectacular leap.

Over the course of the ANC's weeklong conference there will be plenty of talk about President Zuma's alleged corruption, and attempts to unseat him.

There will be angry calls to nationalise South Africa's mines, and seize all white-owned farms. And there will be more sober, sensible debates about how to make this a less unequal society.

It will all matter hugely - and at the same time - make little practical difference.

The ANC has been noisily pondering these questions for years but its leadership is now safely ensconced within South Africa's growing, aspirational middle class, and it seems to have little appetite for revolution.

And so a fractious nation will rumble on.

For me, the most troubling thing today is not the messy politics, or the inequality, or the unemployment - which, when you include the informal sector, is not as high as often claimed.

The really shocking thing is this:

When it comes to primary school education - this country ranks among the very worst in the world. Below Bangladesh. Below Nigeria.

A generation is being forsaken, which makes the smiles of those graduating university students and their cheering families this week, all the more moving - and bitter-sweet.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

- Published14 December 2012

- Published7 December 2012

- Published3 October 2012

- Published29 October 2012

- Published4 October 2012

- Published24 July 2023