Andrew Visser's four-bedroom home in the historic village of Mangotsfield near Bristol, with its views over rolling fields, is just the sort of place he had hoped to raise his two young children. Yet, despite earning a good salary as a software specialist, this 39-year-old does not own the house and sees no prospect of doing so.

Andrew and his wife Amy belong to Generation Rent, an army of millions, all locked out of home ownership in Britain. They are among 60,000 households who rent privately in the Bristol area, more than at any time since the second world war. Rents are being hiked up as demand outstrips supply and the average age of a first-time buyer in the city has risen to 37.

Andrew said: "We moved back to the UK from the US two years ago and had no savings or home equity. I make a good living and could afford to pay a mortgage but the down payment is a problem. I'd need a deposit of £40,000 to £50,000 to buy a similar home to the one we are renting."

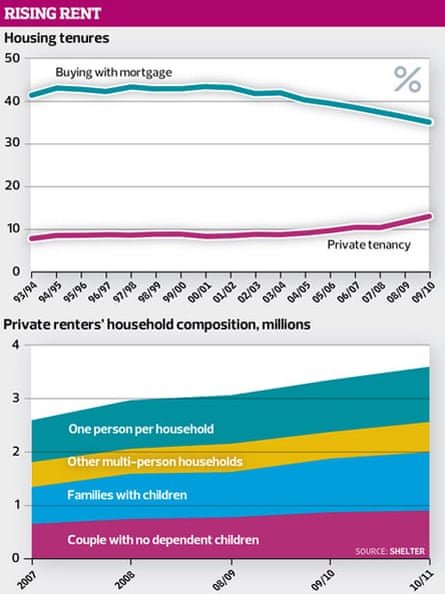

It is a situation replicated across the country where a major transformation is taking place in the housing market and renting is becoming the new norm. The number of households renting in the private sector has more than doubled since the mid-90s, from 8% to 17%, according to Shelter. Traditionally the private rental market was mainly the preserve of students and young professionals but in recent years they have been joined by ever increasing numbers of young families and people in their 30s, 40s and 50s. Of households renting privately, one-third are families and nearly half are over 35, with one in three aged over 45.

Most of these would like to buy – 86% want to own their own home, according to the British Social Attitude Survey – but are stuck in rented accommodation for the foreseeable future.

This week, census figures are expected to show a marked drop in home ownership and a huge increase in the proportion of renters from 2001-2011. As reported in the Observer today, an IPPR report has just revealed the extent of the thwarted aspirations and shelved ambitions among Britain's frustrated renters. How have we got here? And what can be done?

Stagnating wages and the rising cost of living make it impossible to save the tens of thousands of pounds needed for a downpayment, especially when you're paying rent as well. Around 70% of first-time buyers now have help from the "bank of mum and dad", according to the Council of Mortgage Lenders, often thanks to parents remortgaging.

Beside a mortgage famine, there are several other reasons behind the emergence of Generation Rent, namely sky-high house prices, a housebuilding slump, an ageing population and past government housing policies. The number of social housing units has fallen from 5m in 1982, or 30% of the housing market, to 3.85m or 17% of all homes – creating more demand for private rentals.

Roger Harding, head of policy and research at Shelter, explains: "There's a lack of housing stock, which started in the 1980s with council house sell-offs and councils not being able to reinvest the money in housing; then not enough was built under successive governments. Labour spent a lot on improving the condition of existing social housing stock but didn't start building new houses until the credit crunch was kicking in.

"It's a generational thing. Two-thirds of us are still homeowners. One-third of all householders own their homes outright (mostly those over 60); one-third have a mortgage and one-third rent (privately or in social housing).

"What's clear is that the next generation is going to really struggle to get a stable or affordable home, no matter how hard they work or save. While it used to be a reasonable expectation for parents that their children would be better off than them, when it comes to housing things are moving backwards."

Between 2001 and 2011 wages increased by 29% while house prices increased by 94%. In 2001, the average price of a home was £121,769, 7.4 times an average individual salary of £16,557. In 2011, average house prices are £236,518, or 11.1 times an average individual salary of £21,330.

Harding added: "Even if young families aspire to be homeowners, the fact is they are renting now and will be for at least five years. We need to build an awful lot of homes to reverse the trend, about 250,000 a year."

Britain is traditionally seen as a nation of homeowners, to the extent that it appears to have become ingrained in our national psyche. Following Margaret Thatcher's vision of a "property-owning democracy", rates of home ownership grew until 2002 when 69.7% of households owned their own home. By 2010 this had shrunk to 64.7%.

Right now, Andrew Visser is glad he hasn't got a mortgage. Last week he heard he was being made redundant for the second time this year. "The job market is too fragile to commit to paying for a house in a specific location when you might have to move for work. I wouldn't dream of placing a housing millstone around my neck," he said.

For many, home ownership is still an aspiration, often because of the difficulties they encounter renting. The Observer asked readers for their experiences of the private rental market, prompting hundreds of responses on our website. Problems with renting range from the quality of accommodation and the frustration of not being able to make improvements to unpredictable rent increases. Standard tenancies offer little security – typically renters have an assured shorthold tenancy, usually 12 months, then a rolling contract (in which the tenant can give one month notice and landlord two months) – and millions worry about their contract ending before they are ready to move. According to the English Housing Survey, 35% of private renters moved house in 2010-11 compared to 3% of people with a mortgage.

Elspeth Reid, 54, would love her own place in Bristol. In 2008 she returned from a spell working in Andalucia. She owns a flat in Spain which she can't sell and, until she does, she has to rent. She had a bad first experience of renting – "It was hell! It was cold (poor insulation) and incredibly noisy" – but she now lives in a two-bedroom late Victorian house in the south of the city.

Elspeth, a financial director, said: "It is a lovely place to live in with a strong sense of community. There are a lot of people in the area who rent. Even if I could sell my flat and get a deposit I would struggle to buy in this area because the prices are so high. I've got lots of friends and family around – my sister and her twin sons rent nearby and we moved my parents into sheltered accommodation here. I have a lovely landlady and I'm allowed to decorate as I please and have my cat Charlie, which really improves my quality of life.

"But my big fear is that my landlady will decide to sell the house and I will have to move. I have no reason to suppose that she will but it does keep me awake at night quite often."

There are plenty of complaints about letting agents. The more unscrupulous ones "churn" tenants – that is, raise rents suddenly so fees can be charged for drawing up new contracts, or, if the tenant leaves, the agent makes more money for finding new tenants.

Rosa Beard, 26, an editor at a publishing firm in Bristol, had a bad experience of renting before moving to her current flat in the Stokes Croft area with her boyfriend James Flindall, also 26. Of her last place in Clifton, she said: "Mould covered the back walls of our flat. They turned black. The damp was so bad, the broadband cables running through one room eroded, cutting off our internet. We had respiratory problems. We also needed the windows to be replaced because so many were cracked."

After a year, building work began on the top floor. "They ripped up the roof to build new flats, but while the roof was off, there was torrential rain. Our flat flooded in a number of places. We told the company that owned the flats, but they did nothing." After a number of months paying half rent, they moved out and after much wrangling they got their deposit back.

For now Rosa is happy renting and loves the arty vibe of the area, with its coffee shops and bars. In four or five years' time, however, she would like to buy but finds it impossible to save for a deposit. "So much of what we earn goes on rent – all my friends are in the same situation. I want to buy because it gives you more freedom – you can keep a pet or change the carpets, paint the walls. You spend your 20s moving around but you want to settle somewhere eventually."

Andrew Visser has also rented a property which was sub-standard. "In my last place on the other side of Bristol, it was so cold and we had a baby and a two year old. The landlord wouldn't do anything and when we moved out he charged us for repainting the wall where the damp was we'd told him about. Eventually we split the cost. There needs to be more control of landlords. There need to be standards of how fast repairs will be made and local housing officers (the few there are) need more power to make sure houses are fit for purpose – not damp-ridden, unsafe holes."

Shelter said a third of homes for rent in Bristol do not meet basic standards and complaints against private landlords in Bristol have more than doubled in the past three years to 523 in 2011-12. A pilot licensing scheme for privately rented properties is planned to start in the city next spring. This would bring in money for the council to appoint officers to deal with rogue landlords. A similar scheme is being started in Newham in January.

An area that has been little explored is the social impact of renting. On Monday, the IPPR publishes a report looking at these effects. It found that renters feel less attached to their local neighbourhood communities, and are more likely to delay starting a family and building their careers because of the uncertainty around renting and the lack of affordable housing in areas where jobs might come up.

Rosa said: "It's hard to feel part of a community when you move around so much. You might only move 10 minutes away but it's a whole new neighbourhood. I don't want to yet, but if I did decide to start a family later on, I'd like to have my own home and be settled."

For those who are renting with children, there are many uncertainties. A report by Shelter in September, called A Better Deal, showed that more than a third of families renting (35%) worry about their landlord ending their contract before they are ready to move out. Almost half of families with children who are renting worry their landlord will put their rent up to a level they can't afford, and 28% of renters without children do not think it's suitable for bringing up kids. Almost half of families with children do not think of their private rented accommodation as "home".

Kirsten Reid, who has twin sons aged 15, rents a terrace house 15-20 minutes' walk from her sister Elspeth's house. The thought of perhaps having to move one day does play on her mind. Her sons are settled in school and taking GCSEs next summer. "We've been here six years and the landlord is fantastic, the rent's not gone up. But you never know what might happen in the future."

So what can be done to improve life for Britain's growing band of renters? Shelter's Roger Harding said: "In the short term, we've got to sort out the rental market and make it a more suitable place for families. Right now landlords can raise the rent at any time, and evict with just two months' notice. For families with children, this means huge upheaval if they need to move schools, and then there's the worry that it will happen again anyway. Shelter's proposing a new stable rental contract that will give renters five years in their home and some predictability when it comes to rent rises. In the long term, we've got to tackle the shortage of affordable homes by building more."

As planning minister Nick Boles discovered last week, when he talked about building 100,000 new homes on two million acres of countryside, building more houses can be controversial. Housing minister Mark Prisk told the Observer that the government was offering £10bn in loan guarantees and a £200m equity fund to encourage greater institutional investment in building homes specifically for private rent. He added: "For those looking to buy, our FirstBuy scheme offers a valuable alternative to the bank of mum and dad while the NewBuy scheme enables people to buy newly built homes with a fraction of the deposit they would normally require.

"But we also need to build more affordable homes, which is why despite the need to cut the deficit we're investing £19.5bn public and private funding into an affordable housing programme set to deliver 170,000 new homes."

This week Labour's shadow housing minister, Jack Dromey, will launch a wide-ranging review into the sector, canvassing interested parties to come up with ways to make it better for both landlords and tenants. He said: "It is true that housing has not been sufficiently centre stage for a very long time. That has now changed. Housing will be centre stage for Labour in the runup to the election. There are a lot of good landlords but there are major problems of stability, affordability and quality."

A report to be published this week by Labour highlights the situation in other countries where "private-sector tenants have greater certainty in their home but also retain flexibility if they want to move". In Germany, France and Spain renters have longer-term contracts and rent can only be increased by an inflationary index.

All those renters in Bristol will be watching with interest.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion