Grail satellites show Moon's violent history

- Published

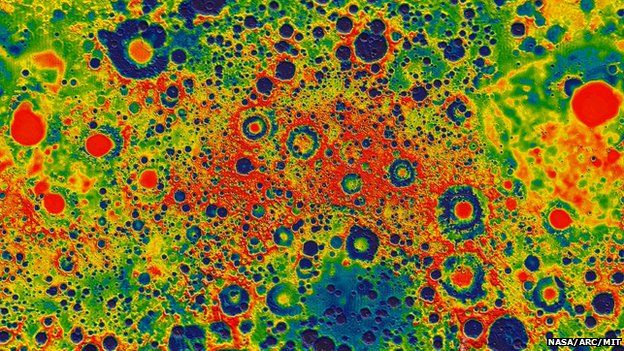

The scale of the battering the Moon received early in its history has been revealed in remarkable new data from two Nasa satellites.

Ebb and Flow - together known as the Grail mission - have mapped the subtle variations in gravity across the surface of the lunar body.

They show the Moon's crust to be a mass of pulverised rock - the remains of countless impacts.

Scientists say the beating was far more extensive than previously thought.

And this observation, they add, has relevance for the study of the Earth's ancient past.

It too would have been pummelled in the first billion years of its existence by the left-over debris from the construction of the planets.

Prof Maria Zuber: It is like the surface of the Moon has gone through a mixer

It is just not obvious today because the Earth's surface has been constantly remodelled through time as a result of plate tectonics. All its early scars have long since healed.

"If you look at how highly cratered the Moon is - the Earth used to look like that; parts of Mars still do look like that," explained Prof Maria Zuber, Grail's principal investigator from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, US.

"This period of time when all these impacts where occurring - this was the time when the first microbes were developing.

"We had some idea from the chemistry [of ancient rocks] that Earth was a violent place early on, but now we now know it was an extremely difficult place energetically as well, and it shows just how tenacious life had to be to hang on," she told BBC News.

Prof Zuber was speaking in San Francisco at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, the world's largest annual gathering for Earth and planetary scientists.

Her 300kg Grail twins have spent much of the past year mapping the Moon's gravitational field from an operational altitude of 55km.

The gravity differences they have been measuring are the result of an uneven distribution of mass across the lunar body.

Obvious examples at the Moon's surface include big mountain ranges or deep impact basins, but even inside the lunar body the rock is arranged in an irregular fashion, with some regions being denser than others.

All this has a subtle influence on the pull of gravity sensed by the over-flying Ebb and Flow satellites.

The Grail twins make their measurements by carrying out a carefully calibrated pursuit of each other.

As the lead spacecraft flies through the uneven gravity field, it experiences small accelerations or decelerations. The second spacecraft, following some 100-200km behind, detects these disturbances as very slight changes in the separation between the pair - deviations that are not much more than the width of a human red blood cell.

And when the gravity measurements are combined with topographical information from another of Nasa's lunar satellites showing the surface highs and lows, it becomes possible to separate out that signal related just to the Moon's internal structure and composition.

The resolution of Grail's maps far exceeds anything previously achieved - a thousand to a hundred-thousand times' improvement.

This will be a boon to researchers as they study not just the general evolution of the body but how individual features on its surface formed - from the largest impact features like the ringed basins, right down to craters just 20-30km across.

One standout observation is that the Moon's crust - its topmost layer - ranges in thickness from 34km to 43km. These numbers are about 10-20km less than previously proposed.

"And because the Moon's crust is extremely important for understanding the bulk composition of the Moon, what these results show is that the bulk abundance of aluminium in the Moon is exactly the same as that in the Earth, whereas previous studies had suggested the composition of the Moon may be different from that of the Earth," said Dr Mark Wieczorek, a Grail co-investigator from the University of Paris, France.

"This is consistent with the hypothesis that the Moon is derived from materials that come from the Earth following a giant impact event."

The crust underlying a couple of major impact basins appears so thin as to be virtually non-existent. This suggests the impacts that rained down on the Moon may even have excavated the underlying lunar mantle at those locations.

The Grail team said that compared to the surface, the interior looks gravitationally very smooth. Indeed, 98% of the gravity signal measured by the satellite twins relates to the Moon's surface features, such as its crater rims and big mountains.

However, the data does point to the existence of long (up to 500km) linear structures that extend up from the interior of the body into the lower crust. The Grail team believes these to be buried dykes — formed from magma that seeped into large fractures in the crust, and then solidified into dense walls of rock.

This may hint at an early expansion phase in the Moon's history when the hot body expanded outwards, before eventually cooling and contracting.

"This had been predicted theoretically a long time ago but there was no direct observational evidence to support this early lunar expansion until this Grail data," said Dr Jeff Andrews-Hanna, a science team member from the Colorado School of Mines.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published18 October 2012

- Published1 January 2012

- Published10 September 2011

- Published6 September 2011

- Published31 March 2011