HOUSTON, TEXAS—Astronauts have been saying "Houston" into their radios since 1965. The callsign refers in general to the Johnson Space Center in Texas, and the people who answer to it sit in the Mission Control Center, located in Building 30 near the south end of the The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) campus. "Mission Control" has been the subject of movies, television shows, and documentaries for decades. It's usually depicted as a bustling room filled with serious folks in short-sleeved white shirts and skinny black ties who shout dramatically about damaged spaceships while frantically pressing buttons on chunky 1960s control consoles. What is it really like, though, to sit at one of those consoles? What do all of those buttons do?

On a sunny morning in early October, I hopped in my car to find out. The Johnson Space Center is about a dozen miles from my home in League City, up the newly constructed NASA Bypass and down the historic NASA Road 1. After a short drive, my photographer and I were in line at JSC's main gate. We were meeting contacts from NASA's Public Affairs Office, and they were going to escort us further on-site to Building 30 for an Ars "Mission Control" tour. Our mission? Explain the technical details behind how the room operated—and what it was like to sit at a console and answer those calls from space.

One small step

This wasn't my first time in Building 30. I visited JSC with some frequency during my time at Boeing, though not often enough for the feeling of wonder to wear off. Some people are awed when they go to St. Paul's Basilica, others by visiting Disney World. To me, neither place holds a candle to the Johnson Space Center—this is the place where, 50 years ago, men and women helped execute the greatest engineering achievement in all of human history.

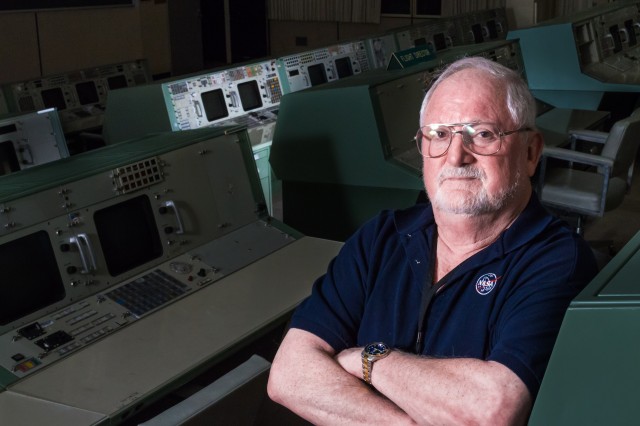

The original plan for my visit was simply to tour the one restored Apollo-era mission control room, to take plenty of pictures, and to give Ars readers a good technical understanding of how "Mission Control" worked during the Apollo era. NASA, however, upped the ante when it assigned my tour guide—none other than Sy Liebergot.

The name should be familiar if you're a fan of manned space flight. Seymour Liebergot, a retired NASA Flight Controller, sat at the EECOM console for Apollo 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15. He was one of the flight controllers responsible for ensuring the safe return of Apollo 13 following the explosion of one of its liquid oxygen tanks (in the film Apollo 13, he's played by director Ron Howard's brother, Clint). Liebergot was present for some of the most monumental moments in space flight, and he was going to walk me through the technical details of Mission Operations Control Room 2. It was like requesting a tour of the Bat Cave and having Alfred show you around the place personally.

JSC looks a lot like a college campus. Situated on 1,600 acres of wetlands between Houston and Galveston, it was constructed during 1962 and 1963, eventually becoming operational in time to shepherd Project Gemini into space. One hundred buildings sit scattered across the property, with the main cluster along NASA Road 1, interspersed with parking lots and neatly maintained green spaces. With the exception of a few recent additions, the buildings of JSC appear every bit the product of their era: 1960s modernist, most mixing terraced concrete and glass. The corridors look like they should exude the odor of decades of cigarette smoke, but the federal government's "no smoking" policy has been in place long enough that most smell faintly of stale coffee instead.

Building 30, which was recently named the "Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center," is a tall and mostly windowless structure, three stories in two wings, joined by a central lobby. Building 30 houses several different "mission control" rooms, which are officially called Flight Control Rooms (FCRs, pronounced "fickers"). When the building was first made operational in 1965 there were a pair of control rooms, then called Mission Operation Control Rooms (MOCRs, "mo-kers").

The MOCRs served NASA through the Shuttle era. The room that housed MOCR 1 has been remodeled and repurposed several times; it is currently used as the International Space Station FCR. MOCR 2, which was used for almost every Gemini and Apollo flight, was restored to its 1960s-era appearance after retirement in 1992. It is now a registered historic landmark.

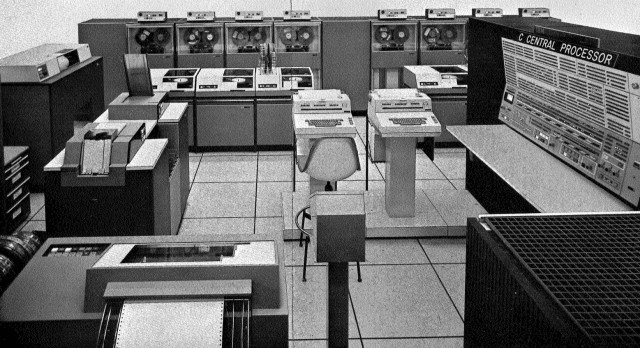

MOCR 2 is on the third floor of Building 30's Mission Operations Wing. The other floors house the Shuttle and station FCRs, as well as FCR support rooms (called MPSRs, for Multi-Purpose Staff Rooms) and office space. The first floor used to house the Real Time Computing Complex, or RTCC, which during Apollo consisted of five IBM System/360 mainframes and their support equipment. As we'll see, the RTCC was a vitally important part of the MOCR's operations.

After passing through the security doors, Liebergot and I rode an elevator up to the third floor. We walked through high-ceilinged corridors with raised floors covered in rubberized tiles, an arrangement which would be familiar to many IT workers. MOCR 2 occupies the central area of the floor, around some corners and past a low alcove containing lockers and a coffee machine. To enter, we walked up a side ramp much like you would find in a movie theater with stadium seating. MOCR 2 is indeed about the size of a small theater—in fact, the room is sometimes used by NASA to screen Apollo 13 and other space films for selected audiences.

The iconic Ford-Philco-designed consoles are arranged in four tiers stepping down from the rear of the room, separated by a glass wall from the visitor's gallery and a pair of press booths. The room is dimly lit by recessed fluorescents, and Sy informed me the room was kept even darker. That way, it's easier to see the console displays.

Once our NASA contact cleared out some picture takers and shut the doors, MOCR 2 was suddenly cloaked in silence. I could feel the ghosts. Here, in this very room, sitting at these sage-colored consoles, 30 years of manned space flight happened. It felt very much like standing in a cathedral—except that this room wasn't just built to talk to the heavens, but to actually visit them.

reader comments

98