If you follow the smartphone patent wars, you've probably heard of the International Trade Commission (ITC), which seems to get dragged into every high-profile patent dispute over the devices. Just this month, Motorola asked the ITC to ban various Apple products from the US, and the ITC separately ruled that Apple doesn't infringe some Samsung patents. But how did this obscure Washington bureaucracy become a major front in the patent wars?

The ITC has the authority to police "unfair methods of competition" by importers, a phrase interpreted to include patent infringement. Because virtually all mobile devices are manufactured overseas, getting the ITC to ban the importation of a device can be just as effective as getting an injunction from a regular court.

A new study from the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, suggests that the ITC's patent-enforcement process is tilted in favor of patent holders—and especially patent trolls. The author, K. William Watson, argues that the inherently discriminatory nature of ITC patent enforcement—ITC cases can only be brought against imported products, not domestically produced ones—violates America's obligations under World Trade Organization rules not to discriminate against foreign products. He says Congress should eliminate the provision of trade law, known as Section 337, that gives the ITC authority over patent issues.

Two bites at the apple

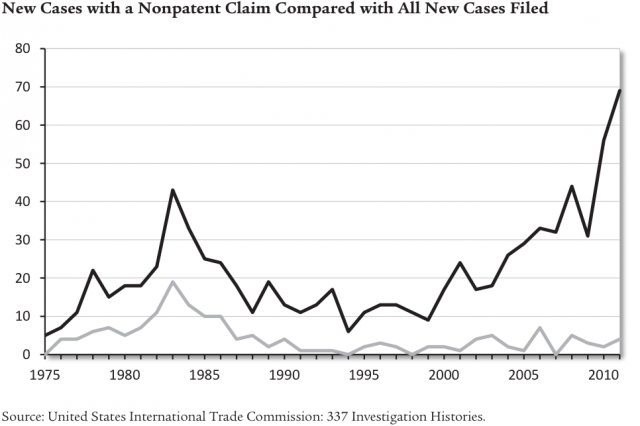

Section 337 has been on the books since 1930, but it didn't see regular use until Congress created the ITC in 1974. In its early years, the ITC handled a mix of patent- and non-patent cases, but in the last decade, the number of patent-related cases brought under Section 337 has exploded.

The popularity of the ITC among patent holders was bolstered by the 2006 Supreme Court decision in eBay v. MercExchange. When a patent holder wins an infringement lawsuit, it is sometimes awarded an injunction against continued use of the patent by the infringer, in addition to monetary damages. The threat of such an injunction gives the patent holder extra leverage that it can use to extract larger settlements. For example, shortly before the eBay decision, the patent troll NTP used the threat of an injunction to force smartphone maker Research in Motion to fork over $612.5 million. But the eBay decision made it harder for patent holders to obtain these injunctions, tilting the playing field a bit more toward defendants.

So patent holders looked for other remedies. The ITC has an injunction-like remedy called an "exclusion order," which instructs customs officials not to allow particular products to be imported into the United States. These turn out to be relatively easy for patent holders to obtain, and the exclusion orders were not affected by the Supreme Court's ruling on injunctions. Hence, after eBay the ITC became the easiest way for a patent holder to get a competitor's products pulled from the shelves.

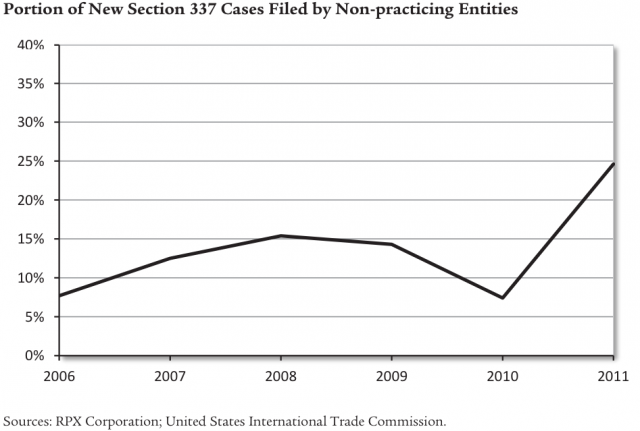

Exclusion orders have proven particularly popular with patent trolls. The eBay standard asks whether the patent holder has suffered an "irreparable injury" due to infringement, and whether an injunction is necessary to repair that injury. Ordinary technology companies can often satisfy this standard. But it's much harder for "non-practicing entities"—patent trolls—to do so, since they can't argue their own products have been hurt by unfair competition. The standard for obtaining exclusion orders is easier for patent trolls to satisfy, however; unsurprisingly, they have accounted for a growing share of the ITC's Section 337 cases.

The ITC favors patent holders in another way as well. Congress has mandated that the ITC resolve Section 337 cases quickly; on average, ITC investigations are resolved in about half the time of patent cases in district court. In principle, faster decisions are a good thing—but in practice, the ITC's strict deadlines can give patent holders an unfair advantage. The patent owner gets to decide when to file a complaint, so it can spend as much time as it wants doing legal research prior to filing. But the alleged infringer can't start preparing its defense until the case is filed. And once the case starts, the defending party has only a limited amount of time to prepare a response.

Finally, the mere existence of the ITC gives an important advantage to patent holders. That's because patent holders get to choose whether to file their cases before an ordinary district court or before the ITC. Indeed, they're allowed to bring cases in both venues simultaneously. Patent holders therefore get two opportunities to argue for excluding the defendant's product from the market. If the two tribunals reach opposite conclusions, the discrepancy might eventually be resolved by the appeals courts, but in the meantime the defendant could be subject to crippling market exclusion.

Not only is this scheme unfair to firms accused of infringing patents, but Watson argues that it is also illegal. The World Trade Organization's rules prohibit member states from passing laws that unfairly discriminate against imported products. And Watson writes that "a dispute settlement panel determined in 1989 that Section 337 violated this national treatment obligation." While Congress has tried to remedy some of the specific issues raised by that ruling, Watson contends that the existence of the ITC is inconsistent with America's treaty obligations.

Watson proposes a simple reform: repeal Section 337 and get the ITC out of the business of adjudicating patent disputes. He argues that the ordinary court system is perfectly capable of handling patent disputes, and that eliminating the ITC's patent-enforcement role would simultaneously improve the fairness of the patent system and reduce a source of unnecessary friction with America's trading partners.

(Disclosure: I'm an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute, an unpaid position. I didn't participate in the preparation of this study.)

reader comments

41