The gates outside Charlotte Church's house are huge, heavy and automated. I press the intercom, but there is no answer. So I stare through the slats up the long, winding drive and acres of garden. There is no sign of the house. This is about as private as private residences get.

Once you know about Church's history, it begins to make sense. It's not that the former child singer announced she wanted to be alone and retreated from the world. Far from it: she loved her friends, her family, and was wedded to her community in Cardiff. No, Church was hounded into privacy. This is the girl for whom a clock was devised, counting down to her 16th birthday, when she would be "legal"; who was labelled promiscuous despite the fact that, at 26, she says she still has only ever had four boyfriends. This is the girl portrayed as a chav, a binge drinker, a fallen angel, a symbol of everything wrong with modern Britain. For others in her family, it was even worse. In February this year, Church and her parents accepted £600,000 in damages and costs after Rupert Murdoch's News International admitted that Church's voicemail messages were targeted repeatedly over a number of years, and that it had unlawfully obtained and published private medical information about her and her mother.

Given all that, perhaps the only surprise is that the gates aren't topped with barbed wire. Eventually, they open slowly, and ominously. I walk up the drive, half expecting to be frisked by heavies, but there's just a gardener mowing the lawn. So I walk some more, past kids' toys and footballs and a wendy house. "Hi-yyyaa," Church shouts. She's in tracky bottoms, scruffy T-shirt, no makeup, chipped nails, and looks perfectly lovely.

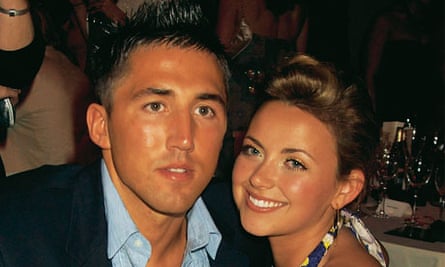

At an age when many young people are still living with their parents or dusting away their student days, Church has lived a dauntingly full life. It's not just the 10m records she had sold by 2007, nor the £25m she was said to be worth in 2003 (now down to an estimated £10m), nor her stint as a very funny chatshow host when she had just turned 20; it's also the relationship with rugby player Gavin Henson, their two children, the separation, the way she combines motherhood with a new music career as an indie rocker, her impressive appearance in front of the Leveson inquiry into hacking and, as a result, now her role as a patron of the pressure group Hacked Off.

A week earlier, we had met at a Rough Trade shop in east London, where she was showcasing her new EP. The audience was 30-strong, and seemed to consist mainly of people who worked in the shop and Church's friends – it couldn't have been further removed from the height of her teen fame, when she performed for the Pope or in front of 20,000 at the Hollywood Bowl. She sang half a dozen songs barefoot on a tiny stage, accompanied by a band (including her boyfriend on guitar), screaming, screeching, whispering and harmonising – part Björk, part Radiohead – and having the time of her life. A pattern soon emerged. "This is one I wrote after reading a piece in the Daily Mail," she said. "Needless to say, I was pissed off." Then she introduced us to Beautiful Wreck, a song about exploitation.

Church's story was always going to be tabloid gold – the working-class Welsh girl who sang like an angel and would be our own Maria Callas. Even better, it was a story peopled with irresistible characters – the pushy mum, the father who wasn't the biological father, the grandad who played guitar and had met the Beatles, the aunt who fancied her chances at stardom, the tough manager, the liability boyfriends, and on it went.

I once read an interview with Church when she was 14 in which the writer described her as "the most fearsomely balanced, joined-up teenager you could meet". I ask her if that rings true. She nods. "Yeah, yeah. Fearsomely balanced – because you've got to work to maintain any sort of balance." Even when she was at her most exposed, she says, she never considered herself unbalanced. "I've never been off the rails in my entire life."

Right from the off, she was misrepresented, she says. We were led to believe she was fantastically ambitious, and her mother even more so. Rubbish, Church says. The only reason she got noticed in the first place was because she turned up with her aunt, who was taking part in a talent contest. When she did become successful, the story is that it ruined her. Again, she says, that's rubbish. She had a wonderful time – travelling the world, always with her mother, Maria, in Washington one day, at the Vatican the next. She even sat one of her GCSEs in the White House, where she had been performing for George Bush's inauguration and wondered why there were so many protestors. Looking back now, she says, it's not her proudest moment politically, but it was still thrilling.

And when she wasn't gigging, she was back at school leading a normal life. Did the other kids bully her about her fame? You've got to be joking, she says. They couldn't care less, and they were her mates, anyway. "You can't forget how self-involved teenagers are. I was 14 and doing massive concerts and selling shit-tonnes of albums, and I'd get back and they'd be like, 'Whatever… So-and-so snogged so-and-so the other week,' who was going out with so-and-so. They'd fill me in on everything that was going on. That was the most important thing." Things couldn't have been better, she says.

So what did go wrong? In 2000, her mother sacked her manager Jonathan Shalit; he eventually received an estimated £2m in an out-of-court settlement. The press monstered Maria. "That was when it turned, and I thought, this is really ugly."

Church insists her mother was simply looking after her – she claims Shalit exploited her financially (he received 40% of her royalties from record sales) and says she did not enjoyed dealing with him. "He was just… odd. I said to my mother, 'If I have to work with that man another day, I'm not singing another note,' and she said, 'OK.' The press turned it into this stereotypical situation where she was the pushy mother."

But Maria wasn't portrayed simply as pushy, but as greedy and mad, too, wasn't she? "Yes. But what she essentially was is strong as hell, because she wasn't going to let anyone overwork me or not let me have a normal childhood. They called her the Welsh dragon, and she was a dragon in a certain sense, but it was only to protect her young."

By this time, Church had already found herself in a compromising clinch with the tabloid press. At 13, she was asked to sing at Rupert Murdoch's wedding in New York. Her management was told she could either be paid £100,000 or she "would be looked upon favourably by Mr Murdoch's papers". It sounds like an episode of the Sopranos, I say.

She smiles. "It is very mob, isn't it? I didn't have a clue who he was. I was told he's a really important man, he'll be able to help your career, and that didn't even matter to me. I wasn't ambitious. I've never been ambitious."

She was flown from LA to New York on Murdoch's private jet. "It was unbelievable. The taps were gold." What was the wedding like? "I thought everybody looked ridiculous because they had all this finery on, but no shoes, because it was antique wood on the boat. There was this young bride, Wendi Deng, and I remember thinking, she's really beautiful and he's really old. That is what my 13-year-old brain said to me."

Murdoch asked her to sing Pie Jesu, which she did reluctantly after telling his people it was inappropriate. "I said, 'Well, it's a requiem – was he sure?' Apparently he was insistent. I remember there were these huge, chocolate-covered strawberries, and he dropped the ring and all his aides came to help him find it – all these people in their finery with no shoes on searching for a ring!"

When did she find out why she'd performed for him? "After the event, because I remember this £100,000 or favours being floated about, and me and my mother were like, 'No way, that's a phenomenal amount of money. No way are we turning that money down. Who is he? Who cares?' I'd much rather have just taken his money and invested it wisely, to be honest." She told Lord Leveson that her management persuaded her to accept the promise of favours.

As it happened, News International didn't keep its side of the bargain. So many stories appeared about Church's private life, from the insignificant to the major, that she began to doubt her friends. "We knew we were watched, there were always journalists outside, whether it was my nan's house, my parents' house, my house. They'd follow me everywhere. We'd say, 'I swear they've got a bug in the house.' But you think that's so far-fetched. It makes you a bit paranoid. You look at people around you, and question everybody." She had a close-knit group of friends who had never given her reason to distrust them, but she started to anyway. "I did cull certain people. I just cut them from my life." She says she has recently been back in touch with some of them and apologised.

Awful though it was, Church always felt strong enough to look after herself. Yes, she was aware of the countdown clock to her 16th birthday (she says it was in the Sun and on two websites, while the Sun disputes that, saying it merely reported on its existence on a website), but tried to ignore it. "They were digging on the whole virginity issue… and the whole of my developing body was just beneath the surface." Not that much beneath, I say. "No, not really," she says quietly. "I read bits and bobs, and it was like, yeuchh."

How did it make her feel? "I'm the kind of person who laughs off everything publicly, because I've always been in public and you can't go around wailing. Probably behind closed doors it made me weird out a bit – to be talked about as a commodity, like you're some kind of geisha."

It was during this period that she read an interview she had given to the Times in which it was suggested that she had expected red carpet treatment when she visited Ground Zero after 9/11. She was devastated to be portrayed as a callous prima donna, and it didn't do much for her career in America. But she was advised to say nothing, and was determined it would not break her.

At 18, she was old enough to drink in a pub, so the press turned her into an alcoholic. Was she drinking? "Yes!" She sounds shocked at the idea that she might not have been. "I was 18, 19. I went to Ibiza on my first holiday with the girls. We were totally reasonable, we had a little villa, we went out, we had a great time. We didn't hurt anyone's feelings, we didn't get into trouble." Again, the fallen angel was too good a story to spurn, even if it wasn't true. "This whole thing was going on at the time – look at our youth, binge drinking, wasting their lives. It was just a great way to point a finger and make me one of the figureheads."

Did she ever puke publicly? "No puking. I fell over on my 18th birthday because there were about 50 photographers in front of me flashing; they'd try to trip you up to get the under-skirt shot, and shout abuse at you to get a reaction."

A couple of years later, when she was in her first trimester and had not yet told her parents, she read about her pregnancy in the Sun under the headline Church Sober Shock. Again, she found it traumatic, but knew she'd have to make the best of it.

It was when newspapers began to pry into the life of her vulnerable mother that she knew things were out of control. In December 2005, the News of the World reported that Maria had attempted suicide. The deliberately misleading front-page splash was "Church's 3-In-A-Bed Cocaine Shock", accompanied by a photograph of the singer, while the first sentence read, "Superstar Charlotte Church's mum tried to kill herself because her husband is a love rat hooked on cocaine and three-in-a-bed orgies."

In her statement to Leveson, Church said what the paper failed to tell its readers was that the suicide attempt was "at the very least in part due… to the fact that she was aware this story was coming out". Maria went on to further self-harm after the story broke because of the impact it had on her. "Her main concern was her parents, my grandparents, and the shame of it all – you know, we come from a Catholic family."

And the information had been obtained through hacking? "Yes, that was entirely through hacking. Even our priest was hacked, Father Richard, who was helping both of my parents deal with this at the time." Her parents came through it, she says, despite the newspapers.

Church is convinced we've not heard the end of hacking – that there's more to come out. She says so many newspapers wrote stories about her based on private information, and has started digging around herself for clues to their origin.

It's almost lunchtime, and Church is driving to the school and nursery where her kids have just started. Does she ever ask herself whether success was worth all this? "All the time. How do you get out of it? You can't. I didn't really think about not being famous, because I'd hardly known a time I wasn't. I was 12 when it started, so it just felt like, 'This is life, this is what it is.' It wasn't like, 'I can opt out.' I didn't think like that. Now I do. Now I think this is an option; I can disappear."

Did she consider living in another country? "This is the thing. The record company wanted me to go to America and my family wanted to go to America, but I didn't. I wanted to stay in Wales where all my family and friends were. I love this country, and I just thought, fuck you, I'm not getting chased out. This is my home."

She spots one of her friends pushing two babies down the street, beeps at her and opens the window. "'Kaiiiiiiia! It's me! You OK? Ta-ra.' She's one of my best friends. I went round to hers yesterday. We had a little party with the kids."

In some ways Church is still so girly that it's hard to believe 15 years have passed since her TV debut. At the same time, she seems older than her 26 years. She says she's changed recently. "You know what? Leveson had a big impact. I became a lot more socially aware, and I'm just much more empowered. Also, putting an end to such a long chapter of my life, it made me a little freer, able to focus and re-evaluate. I've turned into a massive feminist, as well."

Has motherhood changed her? "Yeah. I've always been mature, but I think it's made me more emotional and responsible. And more caring. You want to be as safe as you can possibly be, so that when you go this world is OK, bearable, for your children to grow up in."

Does she share the parenting with Henson? "We've got a good relationship. We're both going tonight to an introductory parents' evening for the school… Oh, shiiiiiit! I'm in the wrong lane." She apologises to the driver she's heading straight towards. "Sorrrrrrrry… Gavin has two overnights a week. It works pretty well when you've got two people who want the best for their children and can leave other baggage behind."

It's funny, she says, she's so often been headline news, but she actually hates causing a stink. She does have the knack, though, I say. She grins. There's the time, for example, she called the Pope a Nazi, and just recently she referred to the Queen as an "old woman" who "had no idea what's going on", for which she apologised. "I really don't like confrontation, believe it or not. I've just got strong opinions… They're easy to come by." Ask her what she thinks and she'll tell you. And sometimes she'll tell you even when you don't.

We collect the kids, who have spent the morning making bread and bring their little rolls home. The two are jabbering away in the back of the car. "Dexter, stop messing with that, please," Church says as her three-year-old son contemplates escaping his seat belt. "Dexter Lloyd!" Her voice is rising, half cajoling, half threatening.

"You went through a red light," five-year-old Ruby says.

"I didn't, darling. It was green, honest."

We get home and the huge gates slowly open. "Nilsson!" she shouts in delight as a labradoodle bounds up to her. "Niiiiilsson! He's named after the singer Harry Nilsson."

Church's boyfriend, Jonny Powell, emerges in his pyjamas. He is an old family friend who used to work in her mother's pub. "Sorry, I'd forgotten you were coming. I would have dressed a little bit more appropriately," he says as he shows me round the garage studio.

"He's a scholar, that boy," Church says proudly when he disappears. "He's a smart, smart boy – he got a scholarship to the Royal College of Music. He's a solo artist, released two albums, brilliant musician, and great with the kids." She says she plans to have a couple more children with Powell.

In the kitchen, the band are eating sandwiches and discussing everything from American indie band Fatty Acids to string theory and the suicide of novelist David Foster Wallace. We could be in the world's smartest student house. Church always planned to go to university – when she was young, she wanted to be a vet or a lawyer – but it never quite worked out. Most of the band have been, and tell her it's not all it's cracked up to be.

A couple of weeks later, we meet in a small room above a pub where she is playing that night. The band are chatting away and eating fruit, just as they were round her kitchen table. Church looks happy. She says it's taken a while, but she finally feels she has found herself musically. When I say the music reminds me of a demented Radiohead, she lights up. "I love that! Thank you! I love Radiohead. Yeah, it's been a long journey, but often I think it takes until you're in your 20s to find your thing."

Would she enjoy the level of success now that she experienced as a teenager? "No. You get stalkers and that kind of stuff. I'd love to have a steady, reasonably sized fan base so it's profitable and I can always make music in a way I want to." She has an idyllic image of herself making music in the garage while the kids are at school, then touring with the family in school holidays.

She's also becoming more active as a patron of Hacked Off, and will be talking at the Conservative party conference this week. It's all very well having an inquiry into press hacking, but it will be of value, she says, only if it leads to change. She insists she would hate to see legislation that muzzled the press, but she does hope that Leveson's report, due later this year, leads to greater accountability. "What I don't really understand is people saying this will compromise the freedom of the press. Was the press really free before, with such a small amount of people running it? I didn't think I had any freedom of speech. Lots of people didn't."

Ultimately, she says, she's one of the lucky ones – she and her family were savaged but have come through it. Plenty don't. "It's not about Murdoch. It's about the whole industry. I don't want to have to live that way ever again. And I don't think anybody else should have to live like that."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion