Story highlights

In cash-strapped Newark, more than 160 police officers were cut from the force in 2010

Analysts say the trend isn't unique -- several cities have cut police forces to save money

Meanwhile, violent crime rates soared 18% nationwide last year

In Newark, one senseless street shooting puts the statistics into terms of human tragedy

Stopped at a red light in a crime-wracked neighborhood of Newark, New Jersey, a 31-year-old woman watched as her friend slumped to the floor after a bullet smashed through the back window of the 31-year-old’s Pontiac minivan.

“I looked back and there was a gunman walking up on my car,” said the driver, who declined to be named out of concerns for her safety.

“I turned away and he fired two more.”

As the shots rang out, she turned the wheel and hit the gas to escape what turned out to be the second fatal shooting that day in Newark, where nearly a sixth of the city’s police force was laid off amid budget cuts about two years ago.

And Newark is by no means unique in implementing police cutbacks to save city money. Meanwhile, violent crime soared 18% nationwide last year, marking the country’s first rise since 1993, while property crime also spiked for the first time in a decade.

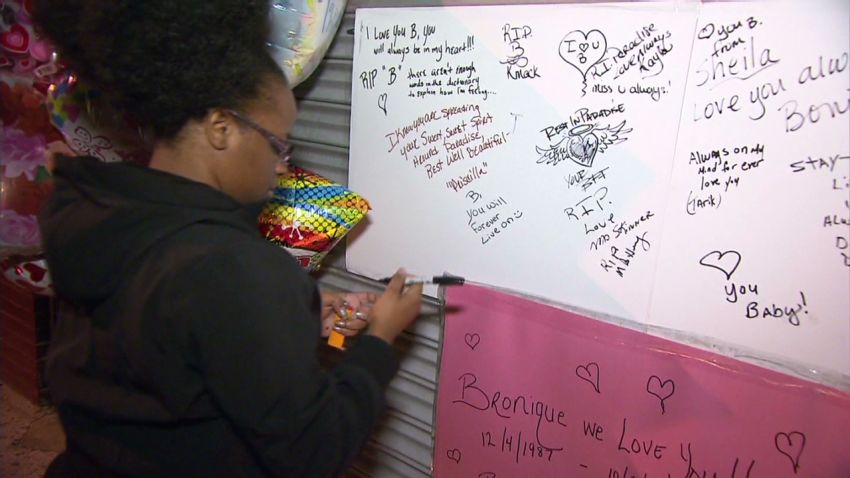

“Hurry up, I can’t breathe,” mouthed wounded Bronique McLeod, after the gunman unloaded three rounds at the minivan where she was sitting with her friends just before midnight on October 1.

The group then raced toward Newark’s University Hospital, but the 24-year-old mother of two began to lose consciousness.

One of the bullets had punctured her lung, her family said later.

“When they got her on the gurney she kept saying ‘I’m dying, I’m dying,’” the driver recalled. “‘Please don’t let me die. I have two kids.’”

McLeod hung on until about 3 a.m. the next day, just hours after another victim died in a hail of gunfire in an unrelated incident about a mile away in the city’s South Ward.

Her death is one of at least 71 homicides so far this year in cash-strapped Newark, where police say they have reorganized after more than 160 police officers were cut from the force in November 2010. Last year the city tallied 74 murders through October, while violent crime soared despite earlier drops in the first years of Mayor Cory Booker’s administration.

Police expenditures in Newark have since declined every year for the last three years, according to the city’s business administrator, Julien X. Neals, leaving cops to sustain public services with decreasing resources.

Analysts say the trend isn’t unique.

“Most cities have cut back since 2008 and the recession, though some more than others,” said Gregory Minchak, a spokesman for the National League of Cities.

Municipal administrators nationwide have since struggled to fill budget gaps amid declines in state aid, a sputtering economy, high employment and slowly rising costs in things like health care and public pensions.

According to the Washington-based cities organization, the effects of the financial crisis are also “increasingly evident in city property tax revenues in 2012,” after dropping 3.9% nationwide last year and thereby bringing in fewer dollars for municipal services.

In short, the overall pie has gotten smaller, say city officials who point to the hundreds of public sector layoffs in Newark in 2010.

“We’ve been in process of reducing our expenses pretty aggressively for the last three years,” said Neals, who touted improvements in the city’s tax collection efforts to help with the revenue side of the equation.

“Naturally there’s a period where the rubber hits the road and there’s not that much left to cut.”

But last year Newark ended up with an $18 million surplus in state aid, prompting Republican Gov. Chris Christie to state that he wasn’t happy with the city’s 2012 requests for more assistance.

“I don’t need New Jersey’s largest city in any more financial trouble than it’s in already,” the governor told reporters earlier this month, dispatching state officials to “force budget cuts.”

Still, in 2010, Newark’s mayor said police layoffs were an “unfortunate situation that was entirely avoidable,” and blamed the cuts on an unwillingness by police unions to negotiate needed reductions in the wake of the financial crisis. Booker said improvements in technologies and partnerships with federal agencies would help in the fight against crime, and pledged to sustain the number of officers patrolling the streets.

But city police union vice president James Stewart has argued that both patrols and detective squads have since been reduced, and that “all the technology in the world won’t replace the bodies you need to respond to crime” and build proactive policing.

Meanwhile, town and city halls in places including Detroit, Michigan; Jacksonville, Florida; Kansas City, Missouri; and Scranton, Pennsylvania, have tentatively put public sector jobs on the chopping block this year to help fill budget gaps.

In January, the mayor of crime-ridden Camden, New Jersey, nearly halved its police force while cutting close to a third of its fire department in an effort to close a $26.5 million budget deficit.

And as America’s fiscal health continues to assume center stage on the campaign trail, how the nation will deal with its debts in the days after November is largely expected to play out in some way on the streets of cities like Newark, Detroit and Camden.

A silver lining may be that it’s finally forcing the discussion.

“We’re now having that frank public conversation about what do we want from government and how much do we want to pay for it,” said Brookings Institution fellow Tracy Gordon.

Law enforcement typically makes up large portions of most municipal budgets and is often considered a prime target for cutbacks.

“Every department is facing the same kind of issues of downsizing,” said Newark Police Director Samuel DeMaio. “Everybody has significantly less amount of police officers and you know there has to be a point where that comes to an end.”

Newark residents such as Latasha Watson, who was a close friend of McLeod’s, say they’ve become frustrated with the response from police, though they are equally disturbed by the so-called “snitch code” that keeps neighborhood witnesses quiet and away from authorities out of fear of retribution.

Newark is listed as one of only a handful of New Jersey cities that maintain gangs with more than 200 members, according to a state survey. “I know (police) are overwhelmed,” Watson said. “People are dying but we want cops on the street doing something,” she added.

Earlier this month, police arrested a 42-year-old city resident who is suspected in McLeod’s murder.