Jonas Mekas, who will be 90 on Christmas Eve, has an intense memory of sitting on his father's bed, aged six, singing a strange little song about daily life in the village in which he grew up in Lithuania.

"It was late in the evening and suddenly I was recounting everything I had seen on the farm that day. It was a very simple, very realistic recitation of small, everyday events. Nothing was invented. I remember the reception from my mother and father, which was very good. But I also remember the feeling of intensity I experienced just from describing the actual details of what my father did every day. I have been trying to find that intensity in my work ever since."

We are sitting at a table in the small kitchen area of Mekas's expansive studio in Brooklyn beneath a fading photograph of Arthur Rimbaud, one of his abiding inspirations. Around us, boxes full of archive material are stacked high in every available space: prints, diaries, rolls of film, letters, essays – all the obsessively recorded evidence of a life lived in thrall to the intensity of the everyday.

The man referred to as the godfather of avant-garde cinema is about to have a long-overdue moment. A survey of his work will open at the Serpentine Gallery in London on 5 December. Simultaneously, London's BFI Southbank will host a major retrospective of his films and video diaries, while, on 30 December, the Pompidou Centre in Paris will present a season of films celebrating his life and work. "I have reached a point in my life where I am finally finishing everything," he says, laughing.

Mekas is an integral figure in the history of what used to be called underground cinema, not just as a film-maker, but as a writer, a curator and a catalyst. In 1969, he helped set up the Anthology Film Archives in New York, which houses the most extensive library of experimental films in existence, and he has since overseen the restoration of many classics of the form. His conversation is peppered with the names of the more famous people he worked with in the golden age of avant-garde film-making in the 1960s, from Yoko Ono to Jackie Kennedy, Allen Ginsberg and the Beats to the Warhol set. Many of these figures ended up in his films, which have in turn influenced the likes of Jim Jarmusch, Harmony Korine, John Waters and Mike Figgis.

Mekas's work is both highly personal and wilfully elusive and, perhaps unsurprisingly, given the dramatic events that he lived though as a young man in Lithuania, tends towards the evocation of memory and personal experience. His great friend and champion, fashion designer Agnès B, memorably described him as "an artist, a scribe and a keeper of memories".

For an 89-year-old, Mekas has something of the eternal, and eternally rebellious, child about him, but his playfulness marks a seriousness of intent that has kept him working – he is still prolific – for some six decades now. Maverick film-maker Harmony Korine summed up his singular spirit: "Jonas is a true hero of the underground and a radical of the first degree – a shape-shifter and time-fucker… he sees things that others can't… his cinema is a cinema of memory and soul and air and fire. There is no one else like him. His films will live forever."

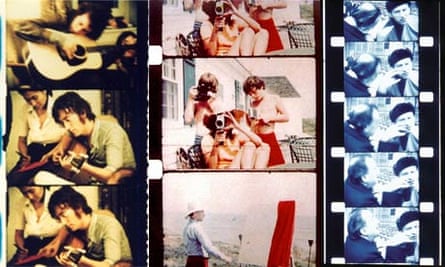

His films are all, to one degree or another, impressionistic biographical diaries. Rejecting drama, suspense, storytelling and linear narrative of any kind, Mekas prefers to document what he calls "the small, intimate moments that describe daily reality without being poetic". His art is one of the jump cut and the fleeting, flickering image, which is often caught on faded colour on a Bolex 16mm camera, then woven into a bigger fabric of moments and memories.

In person, Mekas is a mischievous character, dressed in a blue work jacket and cap, his eyes half-closed and sleepy-looking until he fixes you with a penetrating stare. He was born in the small village of Semeniskiai in northern Lithuania on 24 December 1922. It was a place, he says, "where nothing happened, then suddenly everything happened". As a child, he contacted a mystery illness that left him so thin and sickly looking that the local boys nicknamed him "Death", so he retreated into books and wrote obsessively in his diaries. He was 17, when, in 1940, Soviet tanks rumbled into Lithuania. He hid behind a wall in his village and began photographing them on his first camera, but never saw the results. A Russian soldier angrily snatched his camera and confiscated the film. "Everything changed when the Russians came," he says now. "How we farmed, how we lived, all was swept away."

In 1941, when the German army moved into Lithuania, Mekas joined the resistance, helping to publish a regular, clandestinely distributed bulletin of news culled from BBC radio broadcasts. When his typewriter mysteriously went missing, he buried his diaries in a field and fled the country for Vienna with his brother, Adolfas, fearing the authorities could trace him though the typeface and send him to a labour camp or worse.

Arrested en route, they were taken to a labour camp near Hamburg, where they spent eight months before escaping and hiding in a barn near the Danish border. When the war ended, they were moved from one displaced persons' camp to another for two years. "We watched bad American films to pass the time," he says. "We grew listless and wondered what would happen to us."

Then, in 1949, he and his brother emigrated to America and their lives changed dramatically once more. They lived in a rundown house in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and worked at whatever job they could find, at one point making giant Pepsi Cola signs. A diary entry for April 1950, reprinted in his book, I Had Nowhere to Go, reads: "Life is going on. Nothing new, but we are very busy. Factories and our film obsessions. We have joined a couple of experimental film clubs, just to find out more about what's going on and to meet people. We even screened some footage for them."

How did he make the leap from watching films to making them? "I was 27 and I had to make up for all the lost time in the displaced persons' camp, so I started absorbing everything. I went to the cinema every day. I was so hungry for culture, for stimulation. It was all about grabbing the time, doing something after so many years of doing nothing. And, when my eyes were opened to what others were doing, it was only a small step to start filming."

Mekas's son, Sebastian, arrives in the studio and they exchange small talk for a moment, then a young assistant turns up and moves silently into a corner among the boxes to start working. Jonas fetches a bottle of water from the fridge, then picks up the thread of his extraordinary life story. He tells me that he bought his first Bolex camera with borrowed money just two weeks after he arrived in New York, inspired by the avant-garde films he had seen at Amos Vogel's Cinema 16 film society, where pioneering work by the great Ukrainian-born film-maker Maya Deren was often screened.

Initially, Mekas filmed the Lithuanian community in Brooklyn. (Some of the footage ended up in his 1976 film, Lost Lost Lost.) Back then, he says, he still had the acute longing to return that defines the exile's life abroad. "The memories of home were still very strong, but then, when I got submerged in what was happening and I was entirely in the moment of creativity, the exile feeling faded away."

Soon, he began screening his own short films in small galleries in the East Village and on the Lower East Side. Then, in the spring of 1955, he crossed the Brooklyn Bridge to live in Manhattan and began to film the new people he met and pick up on the new energy in the air. "That's really when my new life began," he says. "People say that I was one of the unlucky ones, but I always say that I was lucky to be exiled and uprooted by circumstance. I was thrown into New York at exactly the right moment when there was all this new energy and attitude erupting everywhere, not just in film, but literature, art, music. That is real good luck. So, really, I don't consider myself a victim, I consider myself one of the lucky ones. Place means nothing to me. I can be at home anywhere."

In New York, Mekas encountered a burgeoning underground culture of artists, writers, musicians, photographers and film-makers, regularly crossing paths with the likes of Allen Ginsberg, film-maker Maya Deren, Robert Frank, John Cage and musician La Monte Young, many of whom came to his Manhattan loft for his regular film evenings. In 1954, he and Adolfas created Film Culture magazine, which analysed cinema in all its forms but concentrated mainly on avant-garde cinema. Among its contributors were director Peter Bogdanovich (who went on to direct The Last Picture Show), experimental film-maker Stan Brakhage and critic Andrew Sarris.

Simultaneously, Mekas started writing a film column, Movie Journal, for the Village Voice. Then, in 1962, he co-founded the Film-Makers' Cooperative and, in 1964, began showing independent films on a regular basis at the Film-makers Cinematheque, both ventures becoming the foundation for what would become the Anthology Film Archives, dedicated to preserving and showing experimental films.

"Virtually everything I created or helped create was done out of necessity," says Mekas. "Film Culture magazine, for instance, was born because we met and discussed films regularly, but there was no voice for us like there was in Britain, which had Sight & Sound magazine, or France, which had Cahiers du cinéma. It was the same with the screenings, which I organised simply because there were so many films that needed to be shown. And, when we started showing them, I then had to put the information out in my column in Village Voice. All of it was driven by necessity."

In 1961, Mekas also made his first long film, Guns of the Trees, an attempt at traditional narrative film-making. "It cost me $15,000, which was so much money then," he says, still sounding dismayed. "This is the only moment I have ever struggled financially in my career and it was a struggle because I was on the wrong track." His following film, The Brig, based on a harrowing stage play of the same name about a day inside a military prison, cost $900 and, though it featured actors and scripted scenes, was so realistic it won the Grand Jury Prize for best documentary in Venice in 1964. A positive review in Cahiers du cinéma began: "When leaving this film, one promises never to see it again. For it seems impossible to watch such a spectacle twice."

In 1964, he was arrested for obscenity after screening a double bill of Jack Smith's sexually explicit Flaming Creatures and Jean Genet's Un chant d'amour, which portrayed homosexuality. That same year, he helped Andy Warhol shoot the footage that became Empire, the pop artist's now famous slow-motion, silent, eight-hour-plus meditation on the flickering, barely changing Empire State Building.

Warhol had been a regular at the impromptu screening nights held at Mekas's Manhattan loft. "We became friends after Naomi Levine [one of Warhol's "superstars"] invited me to his party and I realised it was the same white-haired guy who had come to sit on the floor and watch my films. I always remember that we went to see a La Monte Young performance where one note was stretched out to four or five hours. It was soon after that I helped Andy make Empire. Young was making time stretch in sound; Andy picked up the idea and repeated it visually."

Mekas also befriended the Velvet Underground, allowing them to rehearse in his loft and filming their famous gig at the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry at Delmonico's Hotel in New York in January 1966. Legend has it that it was Mekas and his friend, experimental film-maker Barbara Rubin, who introduced Warhol to Lou Reed.

Another visitor to the loft around that time was Salvador Dalí, who, Mekas says, "felt he needed to be in touch with the younger generation and knew something was happening in New York". Mekas remembers Dalí "clunk, clunk, clunking up the stairs to my floor", where they agreed that Mekas should film one of the artist's impromptu street happenings. On 18 April 1964, Mekas filmed Salvador Dalí at Work, which featured the model Veruschka being tied up on the street by a grinning Mekas and later being covered in shaving cream by Dalí.

Perhaps more surprising still was Mekas's friendship with former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, whom he first met though the artist, photographer and socialite Peter Beard. For a while, he tutored her children, John and Caroline, in film-making. "I spent a few summers in their house in Montauk," he says, smiling. "I wrote the children a little manual and gave them various exercises to do." John Kennedy Jr, it seems, grasped the Mekas method instinctively. "I remember he won an award at school for a multiple-screen, diary-style film he made about his summer holidays."

Mekas also remembers Jackie Kennedy screening his film about the 1960s avant-garde art scene, Walden: Diaries, Notes and Sketches, to "a gathering of her whole clan on mothers' day." What was the reaction? "She cried. They all cried," he says. "It was a very good reaction." For a while, too, Jackie wanted Mekas to make a film about her life and he spent a year or more collecting home movies, family photographs and footage of her and her late husband. "Then, her big TV friends got involved and it was like, 'Who is this guy? We've never heard of him.' They put a lot of pressure on her and it became uncomfortable so I stepped back, but we stayed friends."

In 1999, Mekas released This Side of Paradise, a 35-minute 16mm film about those summers in Montauk with Jackie, her children, and her sister, Lee Radziwill. It followed on from similar diaristic films about George Maciunas, the Lithuanian-born founder of the Fluxus art movement, and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, whom Mekas also befriended in New York.

"I met Yoko back in 1962," he says, "through George Maciunas, who put on one of her first exhibitions. I helped her move apartment and we kept in touch when she went back to Japan and had her nervous breakdowns." To facilitate her return to America, Mekas even created a fake job for Yoko at Film Culture magazine. When John and Yoko arrived in New York in 1976 to set up home there, Mekas was the first person they rang. "It was late at night and I was in bed, when I got a call from Yoko, who had just landed with John at JFK. She said, 'Jonas, John wants an espresso. Do you know a good place that is still open in New York?' It was a little crazy, but that was how it was back then. I took them to the one place I knew that would still be open in the early hours of the morning and John had an espresso and an Irish coffee. I can tell you that he was very happy drinking coffee on his first night living in America."

The short films that Mekas made with these now iconic figures are glimpses of an era when avant-garde cinema was at its peak. From the emergence of the Beat movement in the mid-1950s to the burgeoning of the American hippie counter-culture a decade later, and on into the 70s, Mekas was in the vanguard of that revolution, with highly personal films such as Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1971-72) and Lost Lost Lost (1976), which is made up of six reels that cover his arrival in New York and his interactions with the likes of Robert Frank, LeRoi Jones and, surreally, singer Tiny Tim.

Alongside Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger and Jack Smith, Mekas challenged the commercial orthodoxy of the Hollywood studio system and traditional storytelling just by following his own wayward muse, though when I use the word "experimental", Mekas hauls me up immediately. "No one was experimenting. Not Maya, not Stan Brakhage, and certainly not me. We were making different kinds of films because we were driven to, but we did not think we were experimenting. Leave that to the scientists…

"It is important to know that what I do is not artistic. I am just a film-maker. I live how I live and I do what I do, which is recording moments of my life as I move ahead. And I do it because I am compelled to. Necessity, not artistry, is the true line you can follow in my life and work."

But Mekas, it turns out, has never considered himself in conflict with traditional cinema. "We simply wanted to do something else that could exist alongside Hollywood, but they did not want to let us in. They had built walls around traditional cinema that could not be broken so we had to operate outside those walls in whatever way we could."

In 1960, he tells me, there were just 15 university venues where Maya Deren, a tireless campaigner for avant-garde cinema as well as a gifted film-maker, could show her films. In 1970, there were 12,000. Mekas and his brother, Adolfas, were the prime catalysts of this cultural sea-change.

As I prepare to leave, Mekas gives me a DVD copy of Sleepless Nights Stories, one of his many current projects. It is a film of strung-together moments from the recent past. Faces in close-up flicker on the screen, some familiar – Marina Abramovic, Patti Smith, Harmony Korine, Louise Bourgeois – and some not. It is a meditation on love, memory, friendship and loneliness. "Think about the moment of wrapping a present for a friend or unwrapping a present from a friend," says Mekas, of one of the film's recurring tropes. "It's the essence of those normal moments that I am exploring, the intensity of feeling in them. That is what I have been trying to do for all these years. Really, I am an anthropologist of the small meaningful moment."

At the end of our talk, I ask him what he thinks of contemporary culture and how it compares to the creative iconoclasm that he was part of in 50s and 60s New York. He thinks about his answer for some time. "When the old forms began collapsing and falling away though exhaustion and repetition, a new sensibility is born. That is what happened back then and may be happening now." He tells me how taken he is with the Joseph Conrad notion of the shadow line: a moment of great cultural change that occurs every so often, sweeping all that is old and exhausted out of the way.

"It is overdue," he says, seriously, "but I think the shadow line is falling and things are starting to be born anew. New content needs new forms, new technologies. That is what is happening right now with the internet and digital technology. We have had 40 years of regurgitating the same old stuff and there is a necessity for change. Necessity is what matters." He stands up to shake my hand. "I am hopeful. Always," he says, smiling.

An exhibition of Jonas Mekas's work opens at the Serpentine Gallery, London W2, on 5 December and runs until 27 January. BFI Southbank's season of Mekas's films begins on 6 December.

Sean O'Hagan travelled with American Airlines

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion