A Pittsburgh jury found that hard drive control chips made by Marvell Semiconductor infringe two patents owned by Carnegie Mellon University. Following a four-week trial in federal court, nine jurors unanimously held that Marvell should have to pay $1,169,140,271 in damages—the full sum that CMU's lawyers had asked for.

If the verdict holds up on appeal, it would wipe out more than a year of profits at Marvell, which made a bit over $900 million in 2011. It would also be the largest patent verdict in history, beating out this summer's $1.05 billion verdict against Samsung for infringing patents and trademarks owned by Apple.

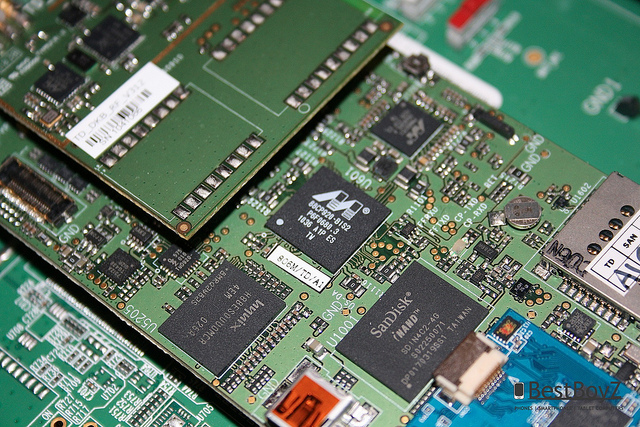

The two CMU patents describe a way of reducing "noise" when reading information off hard disks. The jury found that Marvell's chips infringed claim 4 of Patent No. 6,201,839 and claim 2 of Patent No. 6,438,180. At trial, Marvell hotly contested that CMU had invented anything new; they argued that a Seagate patent, filed 14 months earlier, describes everything in CMU's invention.

Court documents showed that Marvell sold 2.34 billion allegedly infringing chips between 2003 and 2012, according to a report on the case in the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. About half of the chips were sold to Western Digital. Seagate is also a major purchaser of Marvell chips.

There have been patent verdicts larger than $1.17 billion, but none have held up. Alcatel-Lucent was able to nail Microsoft with a $1.5 billion patent verdict over MP3 technology in 2007, but the judge in the case overturned that verdict shortly after trial. In 2009, Johnson & Johnson's Centocor unit successfully sued Abbott Labs for $1.67 billion in patent damages, plus interest, but the patent was knocked out on appeal in 2011.

Marvell is based in Santa Clara and the company is one of Silicon Valley's success stories. Its founder Sehat Sutardja grew up fixing radios in his Jakarta home, ultimately getting his PhD in computer science from UC Berkeley before founding Marvell Semiconductor in 1995.

Universities increasingly involved in patent litigation

The new verdict is the starkest example yet of how universities are becoming more insistent that corporations pay them for their patents.

Some recent examples: Cornell sued Hewlett-Packard over a computer-processor patent and a jury awarded the university $183 million in 2009; the award was later reduced to $53.5 million [PDF]. Northeastern University and an associated startup called Jarg sued Google over a Web patent, and that case settled for an undisclosed sum in 2011. The University of California is co-owner of the Eolas patent, which was notoriously used to claim ownership of any "interactive" website. That patent was invalidated earlier this year, but not before UC was able to collect $30.4 million from Microsoft for a patent license.

And Stanford fought a long-lasting battle against Roche to collect royalties on an HIV testing patent, which ended when the Supreme Court ruled that Roche actually should have been a co-owner of that patent all along.

Universities usually benefit from one of the key advantages enjoyed by pure patent-licensing companies: they can't easily be countersued for patent infringement themselves because they have no products. In 2007, some universities sided with drug companies and patent-licensing companies to oppose patent reform, worried it would hurt their opportunities to make money from their patents.

Some of the new, aggressive university licensing practices were chronicled in a 2007 paper by leading patent scholar Mark Lemley, provocatively titled "Are Universities the New Patent Trolls?"

Still, while many universities may want to plug funding gaps with patent riches, not many can pull it off. As Brian Love, a professor of patent law at Santa Clara University, pointed out, most universities end up net losers in the game of "patent roulette," with their patents costing them more money than they make.

CMU never engaged any company to manufacture products based on the patents-in-suit, according to court documents. That suggests the lawsuit is a case of pure patent-monetization on the part of CMU, notes Love, rather than a research partnership gone wrong.

Marvell still fighting for mistrial

Marvell stock is trading down more than 10 percent following today's verdict. Documents from the case show that Marvell is still awaiting a final ruling on its request for a mistrial, filed shortly before the case went to the jury.

Marvell lawyers said CMU's closing statement was "rife with misrepresentations," including suggestions that Marvell "broke the chain of innovation by not paying the royalties that they now owe," and noting those payments would be used "to fund further research, to lead to further innovation." That resulted in a short conference at the side bar, in which the judge warned "you can't dig deep into all of CMU's contributions to society and mankind."

CMU's attorney also started to compare Marvell's alleged patent infringement to identity theft. "The invention in this case is like your electronic identity, your credit card numbers, your Social Security number," said CMU lawyer Douglas Greenswag. "It's that which [sic] are very personal and valuable to you. You devote years to building up your reputation, your credit rating, your standing. One day Marvell sneaks in—"

At that point he was cut off by an objection and was not able to complete the analogy.

US District Judge Nora Fischer denied Marvell's motion last week, without prejudice, in order to reconsider it again "in light of the entire record, argument, and legal authority."

Fischer has set a schedule for briefing post-trial issues that requires both sides to file motions between February and April of next year, with a motions hearing scheduled for early May.

reader comments

145