Bell's palsy: Facing the TV cameras with half a smile

- Published

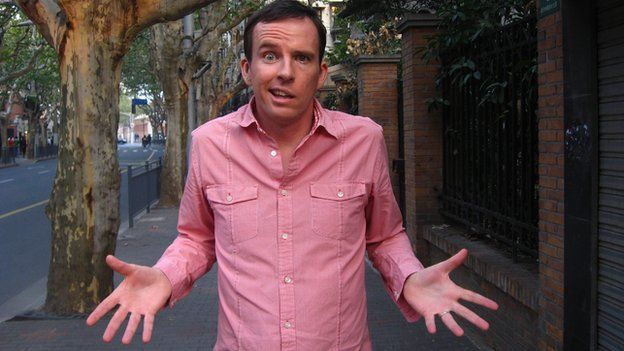

After a lifetime of pretty much doing what I told it to do, one half of my face has decided to go on strike.

From the left side of my forehead to the left side of my chin, every one of my facial features is in complete, open mutiny.

I can't raise my left eyebrow. I can't close my left eye.

And when I try to smile, while the right side of my mouth still obligingly pulls itself into the requisite shape, the left side refuses to budge.

The resulting expression turns out to be useless at signalling a friendly hello but it might come in handy if I ever decide to hold up a corner store.

Welcome to the strange world of a Bell's palsy sufferer.

Bell's palsy is not a great thing to happen to a TV reporter.

That said, it's not a great thing to happen to anyone who needs his or her face and from the many accounts I've seen online, plenty of people carry on with their daily lives.

So I've decided that I will too.

And while I fully accept that my ailment might be about the least important bit of news out of China at the moment, writing about it here means there's a ready explanation for any member of my global fan-base (you know who you both are) wondering why half my face doesn't work when they see me on screen.

But whatever my own reasons, this peculiar and fascinating ailment surely deserves a bit more of a mention - not least because the condition has quite a list of celebrity endorsements.

Both George Clooney and Sylvester Stallone are reported to be past sufferers and both recovered.

Clearly I'm hoping my recovery will be a little bit more like George's.

Bell's palsy owes its name to Sir Charles Bell, the 19th Century anatomist and surgeon-hero of the battle of Waterloo who discovered the function of the facial nerve.

He wouldn't have put it quite like this, but what we now know is that if human beings were cars, then Bell's palsy is the kind of fault that ought to lead to a mass recall. It is certainly a sign of some pretty shoddy wiring.

The facial nerve, on its way from the brain stem - the junction between the brain and the spinal cord - passes through a narrow bony passage close to the ear. At times of lowered immunity, a dormant virus, usually the chicken pox or cold sore virus, can wake up and attack the nerve causing it to swell. Sometimes this can be triggered by an event - in my case a minor injury to my left eye - but at other times there is no apparent trigger at all.

The result of the swelling, though, is a constriction of the facial nerve inside that narrow bony passage, which in turn causes the paralysis.

No matter how hard the brain tries to send messages, from that one point of swelling onwards the face beyond sits there in blissful radio silence.

The thousands of endings into which the facial nerve eventually divides, embedded in cheeks and forehead and lips and eyelids and responsible for every emotion from a smile, and a wink to a frown, are cut off and stranded.

Sir Charles would certainly have noticed the palsied faces on the streets of his native Edinburgh 200 years ago and what is true then is true today. Bell's palsy can strike anyone, of any age, gender or race, and although it's classified as a "rare" illness, it is common enough that about one in 60 people will experience an episode at some time in their life.

The very good news is that most people make a full recovery within the space of a few months.

The nerve, over time, is able to recover and regenerate.

The worrying news is that a significant minority of sufferers are left with permanent effects, sometimes serious. Either way, the condition means at least weeks, sometimes months, coping with facial paralysis, which can of course be difficult, socially at least.

The blogs and postings of other Bell's palsy sufferers show that, for those who don't recover fully, it can be a devastating and life-changing condition. One father writes of his inability to ever appear again in a family photograph.

For me, so far at least, I haven't been too troubled by my onset, and besides, I am of course hoping to recover. So for those interested in following a neurological TV first, my slow progress, or lack of it, can be watched live on the BBC over the next few months.

Of course, with the likes of Clooney and Stallone in his club, old Sir Charles is already used to hobnobbing with real stars.

But now he can claim the odd spot on the Beeb too, and I like to think he would be proud of me.