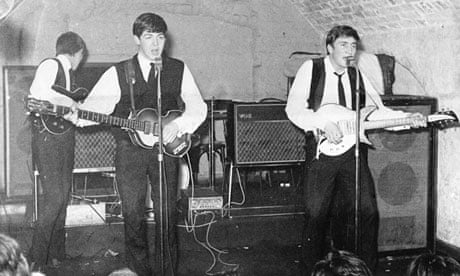

On 5 October 1962, a new sound filled the nation's airwaves. It was raw, simple, direct and sexy. "Love, love me do," sang Lennon and McCartney, "You know I love you." The Beatles had arrived, and a new generation had a new soundtrack to their lives. Seventeen years after VE Day and VJ Day, the war was finally over. Nothing – in culture, in society, in the everyday world itself – would ever be quite the same again.

When, exactly, did the 1960s began? Was it when JFK announced he was running for president (31 January 1960)? When Harold Macmillan acknowledged "the winds of change" sweeping through colonial Africa (3 February)? Or when the chain-smoking Princess Margaret announced her engagement to a commoner, photographer Anthony Armstrong-Jones, on 26 February? Or was it when Kennedy finally won the US election, by a whisker, on 9 November?

Some would go further, and deny that any kind of transition occurred until the new American president had, thrillingly, been sworn in on the icy-blue morning of 20 January 1961. Until then, they say, the west was still in the grip of the sclerotic gerontocracy represented by Eisenhower and Khrushchev. One thing is certain: the 1950s took a while to pass into the limbo of lost time.

In our reckoning with the past, never underestimate the potency of a really good line. For Philip Larkin, the "annus mirabilis" that would confirm his discovery of sexual intercourse, and thereby launch the new decade, famously fell ("rather late for me") between "the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles' first LP". Ever since Larkin, it has become commonplace to suggest that the 60s only struggled out of bed to face the world as late as 1963.

Really? The joyless columns of the almanac contain persuasive evidence that the 60s actually kicked off in October 1962. In the US, for instance, Monday 1 October was the day the first black student, James Meredith, enrolled in the previously all-white University of Mississippi. Civil rights activists were on the move. This was the month that became a hinge between the pinched grey days of the 50s and the Technicolor decade to come.

We are, in other words, about to celebrate the 50th anniversary of a neglected moment when the baby boomers came bursting through the heavily policed doorway of a diminished present into the gaudy playground of the near future. Even before October, 1962 was shaping up nicely as the dawn of a new decade.

In January the first Beatles recording, a song entitled My Bonnie, credited to Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers, was released by Polydor. In February the US put an astronaut into orbit for the first time, when John Glenn was launched from Cape Canaveral on Friendship 7. After three circuits of the Earth, Glenn splashed down in the Atlantic. The race for the moon – a defining 60s challenge – had begun.

On 7 April, in a footnote to the phenomenon not yet known as "popular culture", a certain Brian Jones was introduced to two young musicians, Michael Philip ("Mick") Jagger and Keith Richards, at a jazz club in Ealing, west London. They formed their band, the Rolling Stones, later that year. A documentary to be shown at next month's London film festival is dedicated to what happened next.

On 16 April, there was more music for the ages: folk singer Bob Dylan, who had recently released his debut album, first performed Blowin' in the Wind in a club on West 4th Street, New York City. Meanwhile, on 14 June, Steptoe and Son began a 12-year run on BBC TV where it became, in the words of one critic, "the most popular situation comedy in British television history".

1962 was also a crucial year in the politics of the cold war. In June, the second phase of building the Berlin Wall began. In the months that followed, several East German escapees perished in no man's land, a killing ground of landmines and barbed wire.

Marilyn Monroe was on 5 August found dead in her bed in Los Angeles, from an overdose of Nembutal. The following day, Nelson Mandela was arrested in South Africa; he would later be convicted of sabotage and, having narrowly escaped the gallows, given a life sentence.

Autumn rolled in, and the 60s arrived with the sound of a bluesy "dockside harmonica", and a hint of sadomasochism: the launch of Love Me Do and the UK premiere of the first James Bond movie, Dr No, on the same day, Friday 5 October. The Beatles' raw working-class candour, mixed with Lennon's riff, went into the nation's teenage bloodstream like a drug.

Overnight, it seemed, there was a new style, language, and rhythm, adding up to a new repertoire of private, personal possibility. The contraceptive pill (on sale in the UK from January 1961) was liberating sex from the joyless tyranny of the condom. The 50s "gramophone" was becoming the 60s "record-player". Suddenly the hunt was on, in the words of Lennon and McCartney, for "someone to love, somebody new".

Time flows like a broad river, but history comes in strange eddies and sudden torrents. The prime minister of the day, Harold Macmillan, was once asked about the most likely threat to his government's stability. "Events, dear boy, events," murmured the languid Old Etonian. The credits had hardly rolled on Dr No, and Love Me Do had scarcely begun its climb into the lower reaches of the Top 20, before October 1962 became dominated by two events that would shape the decades to come.

On 11 October, Pope John XXIII opened the Second Vatican Council, popularly known as Vatican II, and the inspiration for Tom Lehrer's celebrated satirical song, The Vatican Rag.

More importantly, it started a process of church liberalisation and sponsored within the Catholic church a reconsideration of marital relations and sexuality. The aftershocks of these debates continue to reverberate through the conservative papacy of Pope Benedict XVI. The issues confronted by Vatican II remain as central to Catholicism as, in international relations, nuclear weapons do to the peace of the earth.

In superpower politics, 1962 remains the archetypal postwar year. On 14 October, the day after the Broadway premiere of Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (which placed another ancient institution – marriage – under the spotlight), a US spy plane photographed four mobile Soviet nuclear missile launchers in western Cuba. On 22 October, Kennedy broadcast that "unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites" had been established in Cuba by the Soviet Union "to provide a nuclear strike capability against the western hemisphere". He went on: "I call upon Chairman Khrushchev to halt and eliminate this clandestine, reckless and provocative threat to world peace." The world held its breath. Was this Armageddon? After the missile crisis, the fate of the earth crystallised progressive thinking on the left. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, founded in 1957, acquired a new purpose. The Aldermaston march, the CND symbol and its slogan "Ban the Bomb" became an integral part of the youth culture of the 1960s, shaping Labour party policy long into the 1980s.

On 28 October, after days of intolerable suspense, Moscow radio broadcast Khrushchev's response, "the discontinuation of further work on weapons construction sites". As Khrushchev promised "to dismantle the arms, to crate and return them to the Soviet Union", the freighters carrying the missiles turned back mid-ocean. In this terrifying standoff, it was said that the Russians had "blinked".

Slowly, life returned to some kind of normality, with seeds for the future, too. On 3 November, the New York Times made the first reference in print to the miracle machine known as the "personal computer". A few days later, on 7 November, an angry Richard Nixon, defeated in the race for governor of California, told reporters: "You won't have Nixon to kick around any more, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference." If only. On the same day, Khrushchev announced that the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba was complete.

In the UK, watching the world crisis from the sidelines, jokes were another weapon: the 60s satire boom was about to explode. On 25 November, the first episode of That Was the Week That Was aired on BBC TV, raising the domestic blood pressure of Tunbridge Wells.

While Britain became accustomed to its role as an attendant lord on the world stage, it was former US secretary of state Dean Acheson who, on 5 December, delivered a brutal critique of our ambitions to play the lead. "Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role," said Acheson. "The attempt to play a separate power role … is absolutely played out."

None of this would discourage the empire dreams that would animate many crucial moments in "the 60s". David Lean's epic Lawrence of Arabia had its worldwide premiere in London on 10 December. A more dystopian worldview was expressed in Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, published just before the end of the year.

Whatever the decade, there's always the weather. On 22 December the "big freeze" gripped the country in an iron fist and didn't let go until March. In this bleak midwinter, Sylvia Plath saw her pseudonymous novel The Bell Jar fall stillborn from the press, completed her Ariel poems, wrote a last letter to Ted Hughes, and put her head in the gas oven. Larkin's "annus mirabilis" had begun. But that's another story.

Looking back, 1962 now seems to be the fascinating antechamber to the great party that was the 60s. But it's also a time capsule. Here are issues – civil rights nuclear disarmament, radical feminism, the dystopian imagination, secularisation – with which we are still grappling. But then the world was young – Lennon was about to turn 22, McCartney was just 20 – and Love Me Do, three words, two basic chords and a pocket harmonica, could change the hearts and minds of a generation.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion