Chemo 'undermines itself' through rogue response

- Published

Chemotherapy can undermine itself by causing a rogue response in healthy cells, which could explain why people become resistant, a study suggests.

The treatment loses effectiveness for a significant number of patients with secondary cancers.

Writing in Nature Medicine, US experts said chemo causes wound-healing cells around tumours to make a protein that helps the cancer resist treatment.

A UK expert said the next step would be to find a way to block this effect.

Around 90% of patients with solid cancers, such as breast, prostate, lung and colon, that spread - metastatic disease - develop resistance to chemotherapy.

Treatment is usually given at intervals, so that the body is not overwhelmed by its toxicity.

But that allows time for tumour cells to recover and develop resistance.

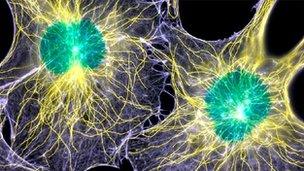

In this study, by researchers at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle looked at fibroblast cells, which normally play a critical role in wound healing and the production of collagen, the main component of connective tissue such as tendons.

But chemotherapy causes DNA damage that causes the fibroblasts to produce up to 30 times more of a protein called WNT16B than they should.

The protein fuels cancer cells to grow and invade surrounding tissue - and to resist chemotherapy.

Success v failure

It was already known that the protein was involved in the development of cancers - but not in treatment resistance.

The researchers hope their findings will help find a way to stop this response, and improve the effectiveness of therapy.

Peter Nelson, who led the research, said: "Cancer therapies are increasingly evolving to be very specific, targeting key molecular engines that drive the cancer rather than more generic vulnerabilities, such as damaging DNA.

"Our findings indicate that the tumour microenvironment also can influence the success or failure of these more precise therapies."

Prof Fran Balkwill, a Cancer Research UK expert on the microenvironment around tumours, said: "This work fits with other research showing that cancer treatments don't just affect cancer cells, but can also target cells in and around tumours.

"Sometimes this can be good - for instance, chemotherapy can stimulate surrounding healthy immune cells to attack tumours.

"But this work confirms that healthy cells surrounding the tumour can also help the tumour to become resistant to treatment.

"The next step is to find ways to target these resistance mechanisms to help make chemotherapy more effective."

- Published9 May 2012

- Published7 May 2012

- Published12 September 2011