Nasim Abu Zaid's youngest son was born into terror, his first 17 months distinguished by the sound of shelling and shooting. Three months from now, the young Syrian mother will give birth again, this time in circumstances that are less life-threatening but characterised by destitution, misery and choking swirls of sand in a relentless wind.

Home for Abu Zaid, 29, her husband and their four young children – and thousands of other refugees from the violence in Syria – is now a desert tent city in northern Jordan. Days are dominated by a wearying and unwinnable battle to keep the sand at bay and the fear of losing a child among the near-identical rows of flapping tents and thousands of displaced youngsters.

But at least the Abu Zaids have escaped the horrors of Dael, north of Deraa. They left the town around six weeks ago, part of a stream of people fleeing across the border to Jordan. In the past week or two, that stream has become a river of desperate humanity: mainly women and children, moving under the cover of darkness, clutching only their fear, each other's hands and the odd plastic bag of possessions.

Zataari refugee camp, opened by the Jordanian government at the end of July to house 500 people, has swollen to a population of more than 26,000. Two-thirds of them are children, of whom around 5,000 are under the age of four. Five hundred are "unaccompanied minors" – youngsters who made the perilous journey without their parents, and who are now dealing with the pain of separation along with new privations and the traumas they left behind.

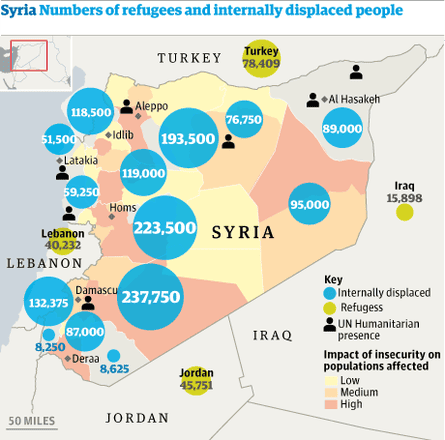

Official expectations are that Jordan's refugee population will grow by up to 10,000 a week. The Jordanian government says there are a further 140,000 Syrian refugees crammed into towns and villages close to the border. Turkey, Lebanon and Iraq have also seen huge influxes of refugees, with thousands more still trying to leave Syria.

At Zataari, conditions are wretched despite sterling efforts by humanitarian organisations. Sand and dust whipped up by the wind sweeping across the nine-square-kilometre site cause respiratory problems. Newly erected tents are swiftly coated in a layer of sand, turning their colour from white to brown within a day or two. Sand is in children's hair, eyebrows, eyelashes, under fingernails; eyes are rimmed red; voices hoarse.

Only 40% of the camp has electricity. There is one latrine per 50 refugees. For now, the desert sun beats down on the exposed ground for 12 hours a day, but within weeks night temperatures will plummet and winter will bring driving rain and freezing winds.

The Jordanian army maintains a heavy presence inside and outside the camp. Refugees are not allowed to leave without special permits. Less than two weeks ago, a protest by camp inmates over conditions and frustration at the tight security was quelled by teargas fired by soldiers.

Bulldozers, earth movers, water tankers, delivery and garbage trucks rumble continuously through the camp's entrance, a serious hazard to hundreds of people milling around aimlessly. The United Nations agency for refugees, UNHCR, acknowledges the camp's problems but insists the priority is to get infrastructure in place for the existing population and the refugees expected in the coming days and weeks.

The high proportion of children in the camp presents particular challenges. "Many children coming across [the border] are traumatised and some are injured," says Pip Leighton of the UN children's agency, Unicef. "There is huge psychological stress. Many of them have seen things that no adult should see, let alone a child."

Agencies such as Unicef and Save the Children are offering specialist counselling and therapeutic activities. "These kids are telling stories that are pretty frightening," says Hedinn Halldorsson of Save the Children. "Some have been in hiding for months. Many are waking in the night, crying. Some children are panicking when they hear the planes [from a nearby Jordanian military base] overhead."

In many cases, fathers have stayed behind in Syria in the hope of protecting property and caring for livestock. "Separation is traumatic," says Halldorsson.

Humanitarian agencies have set up designated play areas, and are working on establishing schools within the camp. "But some days we do nothing but help parents search for lost children," says Rae McGrath of Save the Children.

Abu Zaid says that, whatever the problems of the camp, it is better than what the family left behind. "I was very afraid – the shelling was all around us. All the time the children were terrified and not sleeping," she says. "This is not how we are used to living. We're adjusting. But the children have started playing again. At home, they were locked inside the house."

Miriam, 11, who has been at Zataari for two weeks after fleeing from Sawara with her mother and five siblings, says she has no idea how long the family will stay. Her father stayed behind to take care of the family's cows. "I'm worried about him," she says.

Abed, 12, from Deraa, was smuggled through the mountains at night with his mother, three brothers and four sisters. "I was scared," he says, but adds: "Here we feel safe."

Most of the refugees cross the border east of the official – but now closed – crossing at the town of Ramtha. The nightly numbers hit a peak of 3,300 last week; a subsequent drop is attributed to the period of a full moon.

Most of the women and children are smuggled under the protection of rebels; some men bring their families and then return to Syria. The refugees are brought in buses to the camp, usually arriving while it is still dark. After registration and a meal, families wait to be allocated a tent.

"We're all just about keeping ahead of the problem," says Leighton. "But if there was a massive influx, we would have significant challenges."