Five media myths of Watergate

- Published

The run-up to the 40th anniversary of the Watergate break-in — the burglary that gave rise to America's gravest political crisis — has inevitably been accompanied by the mythology that has shaped and distorted popular understanding of the epic scandal.

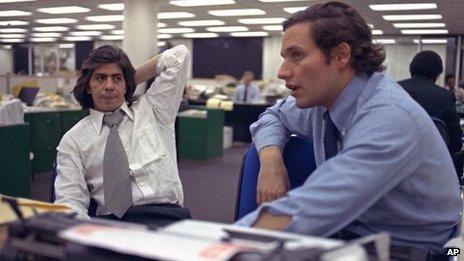

The mythology is both delicious and durable, and revolves around the Washington Post and its Watergate reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. They are legends in American journalism, not only because of their award-winning reporting but because of the screen adaptation of their book about Watergate, All the President's Men.

The movie came out in 1976 and starred Robert Redford as Woodward, and Dustin Hoffman as Bernstein. The New York Times called it "a spellbinding detective story". And the Post once described All the President's Men as "the best film ever made about the craft of journalism".

It is undoubtedly the most-viewed of the handful of films and documentaries about Watergate, the scandal that toppled President Richard Nixon and sent to jail 20 men associated with his administration or his 1972 re-election campaign.

All the President's Men was more than merely entertaining. It was a vehicle for propelling and solidifying prominent media myths of Watergate, five of which are discussed here:

The Washington Post brought down Nixon's corrupt presidency: This long ago became the dominant narrative of the Watergate scandal. It holds that Woodward and Bernstein, through their dogged reporting, revealed the crimes that forced Nixon to resign the presidency in August 1974.

That's also the inescapable, if tacit conclusion of the movie, which places Woodward and Bernstein at the centre of Watergate's unravelling while minimising or ignoring the far more decisive contributions of subpoena-wielding investigators.

Rolling up a scandal of Watergate's dimension and complexity required the collective efforts of special prosecutors, federal judges, both houses of Congress, the Supreme Court, as well as the Justice Department and the FBI.

Even then, Nixon likely would have survived the scandal if not for the audiotape recordings he secretly made of conversations in the Oval Office of the White House. Only when compelled by the Supreme Court did Nixon surrender the recordings, which captured him approving a plan to divert the FBI's investigation of the break-in.

Interestingly, principals at the Washington Post have periodically scoffed at the dominant narrative of Watergate. Woodward, for example, once said "the mythologising of our role in Watergate has gone to the point of absurdity, where journalists write… that I, single-handedly, brought down Richard Nixon. Totally absurd".

The Post, at least, "uncovered" the Watergate story: Not quite. Watergate began as a police beat story. News of the scandal's seminal crime — the thwarted break-in of 17 June 1972, at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex in Washington DC — began circulating within hours.

The opening paragraph of the Post's front-page report about the burglary made clear that the details had come from investigators. It read: "Five men, one of whom said he is a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, were arrested at 2:30 a.m. yesterday in what authorities described as an elaborate plot to bug the offices of the Democratic National Committee here."

Nor did the Post uncover crucial elements of the deepening scandal, such as Nixon's secret taping system. Existence of the White House tapes was disclosed in 1973 to an investigating committee of the US Senate.

And as Edward Jay Epstein pointed out in a brilliant essay in 1974, the Watergate reporting of Woodward and Bernstein was often derivative and sustained by leaks from federal investigations into the scandal.

The stealthy Watergate source Deep Throat famously advised Woodward to "follow the money": That pithy and often-quoted line supposedly was the key to unlocking the complexities of Watergate. In fact, it was born of dramatic licence.

"Follow the money" was spoken not by the real-life Deep Throat source but by Hal Holbrook, the actor who played Deep Throat in All the President's Men.

In real-life, the Deep Throat source conferred periodically with Woodward (sometimes in an underground car park) as the scandal unfolded. But he did not advise Woodward to "follow the money".

Woodward and Bernstein were already on the money trail: One of their most important stories was to describe how funds donated to Nixon's re-election campaign had been used for the Watergate break-in. But unravelling the scandal was far more demanding than following the money. Nixon resigned not because he misused funds donated to his 1972 campaign but because he clearly obstructed justice.

Deep Throat, by the way, revealed himself in 2005 to have been W Mark Felt, formerly the FBI's second-ranking official. He was no hero, though.

Felt was convicted in 1980 on felony charges related to break-ins he had approved in the FBI's investigations into the radical Weather Underground organisation. But Felt never went to jail. He was pardoned in 1981 by President Ronald Reagan.

Their Watergate reporting placed Woodward and Bernstein in grave danger: Hardly, although All the President's Men says as much. In a scene near the close of the movie, Deep Throat tells Woodward that the reporters' "lives are in danger".

The warning, which injected drama into the movie's sometimes-leaden pacing, also was mentioned in All the President's Men, the book. However, it was fairly quickly determined to have been a false alarm.

Robert Redford: 'I came in when journalism had reached an apex of morality and professionalism'

Woodward, Bernstein and senior editors at the Post took precautions for a while to avoid the suspected electronic surveillance of their activities. But as Woodward recounted in The Secret Man, his 2005 book about Deep Throat, such measures "soon seemed melodramatic and unnecessary. We never found any evidence that our phones were tapped or that anyone's life was in danger".

On another occasion, Woodward said the "most sinister pressure" he and Bernstein felt during Watergate "was the repeated denial" by Nixon's White House "of the information we were publishing" as the scandal deepened.

University enrolments in journalism courses soared because of Watergate: It's an appealing subsidiary myth, that the Watergate exploits of Woodward and Bernstein, as dramatised by Redford and Hoffman, made journalism seem glamorous and alluring. So alluring that young Americans in the 1970s supposedly thronged to enrol on journalism courses.

It's a myth that endures despite its thorough repudiation by scholarly research. One such study, financed by the Freedom Forum media foundation, reported in 1995 that "growth in journalism education" resulted "not from such specific events as Watergate… but rather to a larger extent from the appeal of the field to women, who have been attending universities in record numbers".

The study was unequivocal in stating that "students didn't come rushing to the university because they wanted to follow in the footsteps of Woodward and Bernstein — or Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, for that matter".

A similar study, released in 1988, declared: "It is frequently, and wrongly, asserted that the investigative reporting of Woodward and Bernstein provided popular role models for students, and led to a boom in journalism school enrolments."

Instead that study found that enrolments already had doubled between 1967 and 1972, the year of the Watergate break-in.

W. Joseph Campbell is a professor at the School of Communication at American University in Washington, DC. He is the author of five books, including Getting It Wrong: Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism (2010). He blogs about the myths of journalism at Media Myth Alert.

- Published22 April 2012

- Published29 March 2012