Sea ice in the Arctic has melted faster this year than ever recorded before, according to the US government's National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC).

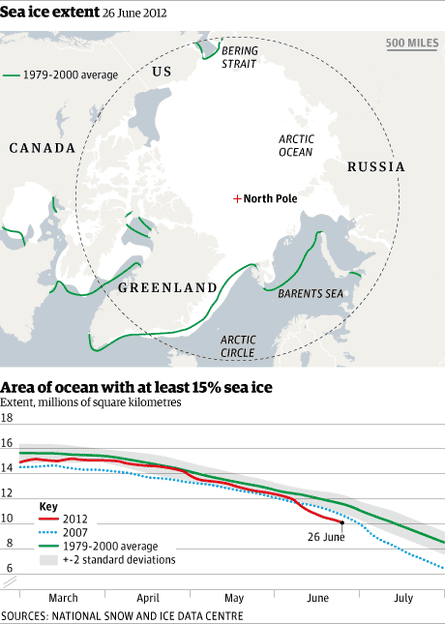

Satellite observations show the extent of the floating ice that melts and refreezes every year was 318,000 square miles less last week than the same day period in 2007, the year of record low extent, and the lowest observed at this time of year since records began in 1979. Separate observations by University of Washington researchers suggest that the volume of Arctic sea ice is also the smallest ever calculated for this time of year.

Scientists cautioned that it is still early in the "melt season", but said that the latest observations suggest that the Arctic sea ice cover is continuing to shrink and thin and the pattern of record annual melts seen since 2000 is now well established. Last year saw the second greatest sea ice melt on record, 36% below the average minimum from 1979-2000.

"Recent ice loss rates have been 100,000 to 150,000 square kilometres (38,600 to 57,900 square miles) per day, which is more than double the climatological rate. While the extent is at a record low for the date, it is still early in the melt season. Changing weather patterns throughout the summer will affect the exact trajectory of the sea ice extent through the rest of the melt season," said a spokesman for the NSIDC.

The increased melting is believed to be a result of climate change. Arctic temperatures have risen more than twice as fast as the global average over the past half century.

Shipping companies said they would be able to send more ships to China and Japan through the previously impassable waters north of Russia if the ice continued to melt so fast. The "northern sea route", which normally requires ice breakers, cuts about 4,000 nautical miles off a journey from Europe to China and can save tens of thousands of pounds in fuel bills.

"This year we expect to send six to eight vessels through the north-east passage, compared to none just a few years ago. There are advantages but there are extra costs and it needs special ships," said a spokesman for Copenhagen-based Nordic Bulk Carriers, the first company to use the northern sea route in 2010.

More open water during the summer is expected to help Russian, US and European oil companies to move into the Arctic. This week Norway announced plans to issue oil and gas exploration permits for up to 86 offshore tracts, most of them in Arctic waters, by the end of 2013. Russian companies have already drilled exploratory wells and Shell is preparing to sink two exploration wells in US Arctic Ocean waters – one between Alaska and Siberia and north of the Bering Strait, the other in the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska.

The record speed of ice melt in the Arctic this year coincides, but is not necessarily linked to heatwaves in Siberia, record temperatures in eastern US and some of the most extreme weather ever recorded in the UK and northern Europe. The link between melting Arctic ice and extreme weather in the northern hemisphere is not established, but the UK Met Office and recent scientific reports have suggested that declining sea ice is linked to colder winters.

Marine biologists this month said that the warming Arctic could be having major ecological effects. Scientists funded by Nasa working 100km from the nearest unfrozen waters reported in the journal Science that they had last year unexpectedly found vast concentrations of microscopic phytoplankton – the foundation of the marine food chain – under the ice, which they described as like finding a rainforest in the desert. Until now, they had believed phytoplankton grew only in open water.

The massive sub-glacial "algal bloom", they said, could be a sign that as the that the ice may now be thin enough to allow sunlight to catalyse algal blooms without it melting completely. "We were astonished. It was completely unexpected. It was literally the most intense phytoplankton bloom I have ever seen in my 25 years of doing this type of research," said Prof Kevin Arrigo, a scientist at Stanford University in California.

The findings, if confirmed, could affect the global carbon cycle because phytoplankton absorb carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion