From July 2009 until December 2010, a Minneapolis-based company called Streaming Flix allegedly hit on a hugely profitable business model—slapping steep monthly fees for its online movie service on the phone bills of 253,269 customers. In total, $9.7 million was billed in that year and a half. How many movies did Americans watch after spending all that cash? 23.

That's no typo—and it means an average of $422,000 was spent each time someone streamed a film. It also suggests that 99.99 percent of the people paying monthly fees for the service weren't using it.

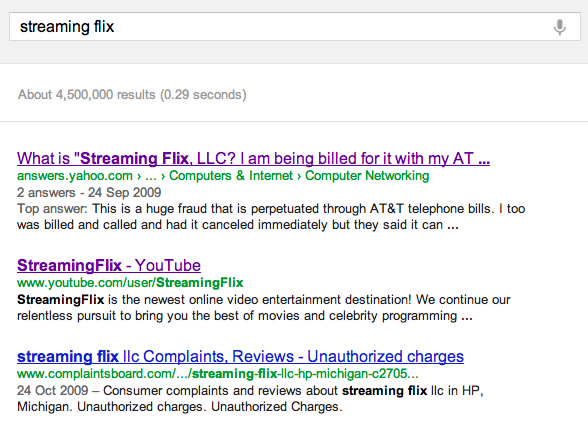

Perhaps that's why the very first Google hit for "Streaming Flix" points to a question from one Barbara G. She wants to know what the company is and why "I am being billed for it with my AT&T bill but did not sign up for it?" The situation grew so bad that the FBI opened a probe of Streaming Flix and its related companies. In December 2010, the Bureau asked the public to send in complaints about the company.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, which has recently taken a strongly litigious view of the matter, Streaming Flix was a massive "cramming" operation. The company used deceptive tactics to bill people for services through their local phone bills. There, charges would often go unnoticed for months. This practice, called Local Exchange Carrier (LEC) billing, is legal and can have legitimate uses—but it's widely known as a vector for cramming schemes.

This one appears to be particularly brazen. According to the feds, a long-time LEC biller named Cindy Landeen was behind Streaming Flix. The company went so far as to bill "internal business lines at AT&T," "customers who lacked Internet access," and "at least 16 deceased consumers."

Complaints rolled down like a mighty flood as outraged customers discovered the charges and demanded their money back. (A whopping 46 percent of all customers billed obtained at least one credit, a shocking stat in a world where credit card companies will cut off merchants with "chargeback rates" above one percent). Verizon refused to accept billings from Streaming Flix in July 2010 as the complaints mounted; AT&T also refused to take new billings from the company.

But the FTC said that the middleman between Streaming Flix and the phone companies, a "billing aggregator" called Billing Services Group (BSG), kept going. BSG placed new Streaming Flix charges with other phone companies who hadn't yet cut off the money spigot. According to the feds, BSG didn't stop working with Streaming Flix until the FBI actually raided Cindy Landeen's offices in Minneapolis back in late 2010.

Streaming Flix wasn't the only company Landeen ran. She also oversaw MyIproducts, 800 Vmailbox, and Digital Vmail—all services that used LEC billing to offer voicemail service that almost no "subscriber" actually used. (Between July 2009 and March 2010, tens of thousands of people were billed but only 209 ever used their mailbox). The total amount billed for these services in less than a year: $30 million.

Landeen also ran "identity theft protection services" ($4 million billed), "directory assistance services" ($8.4 million billed), and even "a job skills training service" (a mere $277,000 billed). Clearly, serious money was at stake.

The Landeen case is under FBI jurisdiction, but the FTC recently filed a civil action against BSG, the billing aggregator, on the grounds that it must have (or at least should have) known exactly what was going on and failed to stop it. The FTC wants $52 million back from the company.

How cramming works

Back in 2008, I got crammed with four "mystery charges" on my phone bill for services I had never heard of, much less ordered. The company billing me was ESBI, now a unit of BSG (the FTC went after ESBI over cramming issues back in 2001). Curious about whether these "billing aggregators" knew that they were billing for unbelievably dodgy services, I called up ESBI to dispute some of the $48.21 in monthly charges that had appeared on my phone bill. I was asked for my phone number, then for my address.

"Why do you need that?" I asked.

"To verify your account."

"But you slapped a $14.95 charge onto my phone bill without verifying my account. Isn't it odd that you care about security now?"

"Sir, I have to enter it in the computer."

After much back and forth, all three firms allowed me to proceed without providing a complete address, and all three firms then provided the address of whoever had allegedly signed up for their "services." This address, which turned out to be the same for all four of the charges on my AT&T bill, was not mine. Despite this, each company allowed me to proceed and to dispute the charges.

"Why did you ask me to verify my address when you don't actually require it to match what's on the account anyway?" I asked. "What kind of verification is that? What possible purpose does that accomplish?"

I received no good answer. Each operator was polite, even cheerful. Each agreed to refund my charges immediately, and each offered the exact same explanation of why I was billed in the first place. "Someone must have made a mistake when typing their phone number into some form online, and they entered yours instead," I was told.

I asked each operator if I understood this correctly: the company they worked for was billing people based on nothing more than phone numbers typed into online forms? The company conducted no sort of verification at all on these accounts? That is, if I went online right now and entered their (the operators') phone numbers into these same online forms, they would be billed? And they had no problem with that sort of setup?

Not one bit. In fact, each assured me that they did not get many calls about this issue, a claim that even the most cursory Web searching is extremely dubious. In the new BSG case, the government said that services like Streaming Flix routinely violated BSG's own extremely liberal "15 percent" complaint threshold—sometimes by huge margins.

In my case, someone had entered my phone number into a "prize draw" website which signed up everyone who entered for multiple monthly services. Such practices continue. When the FTC looked into Landeen's businesses, it found that the bills being generated were based on Internet "offer" pages that "appeared to be part of the sign-up process for an unrelated, free service or event, such as voting in a picture contest or obtaining a free e-mail account."

As consumers clicked through the Web pages related to these free events or services, the offer pages for the crammed services appeared several pages into the click-through and appeared to be part of the unrelated sign-up. Indeed, the offer pages were pre-populated with information (such as name, address, and phone number) that consumers had initially entered to obtain the free e-mail account or to vote, and contained a prominent heading such as “You’re Almost Ready to Cast Your Vote!” or “Your E-mail Account is Almost Ready!” Though the offer pages “disclosed” the service, its cost, and that it would be billed to the user’s telephone number, these disclosures appeared in a lengthy block of tiny text sandwiched between the large-print headline and the pre-populated data fields.

This enraged many of those billed. FTC investigators unearthed a few phone calls from disgruntled "customers." One, calling from a law firm, was told that someone named "David Jones" had signed the firm up for voicemail services. "Nice gig you guys got," replied the caller. "I got seven employees, and we don't have any Davids or any Joneses."

Another woman complained that she had been billed for Streaming Flix even though she didn't own a computer and even though the Streaming Flix "order" was in her ex-husband's name. "But this is not right, how somebody can put something on my phone bill that I don't even have and I have to pay it," she pleaded. "The phone is in my name, and I did not okay this."

As one rep admitted when an angry customer called about charges in her son's name, "Well, he may have been on one of our advertising affiliate sites and thought he was signing up for something else."

Such schemes enrage and aggravate at every level, from individual consumers to the federal government to state attorneys general. Speaking at a 2011 FTC panel on cramming, Illinois Assistant Attorney General Beth Blackston recounted her horror stories for the audience.

"One vendor in 15 months billed 3,650 Illinois consumers approximately $800,000," she said. "And this is one of my favorites, in one case 9,842 Illinois consumers were billed for credit repair services. And when we drilled down a little bit on the phone numbers that were billed, we found—this is for credit repair services—Steak ‘n Shake, our county coroner’s office, a Super 8 lodge, and our local public library’s story line, which is just a recording."

reader comments

81