When Mary Portas arrives in a new town centre, she sniffs – literally inhales the local air in her nostrils. She has visited hundreds of high streets over the years, initially in her day job as a retail guru and, since May 2011, heading up an independent review for David Cameron's government, and she claims – though it is sometimes hard to believe – that every one is unique.

"You need to get a feel for what consumers want," she says, sitting at her desk in central London, her 3in heels on the top. "I can't go: 'This is a solution for Margate,' if I don't see how Margate lives. It's like going into a big store: you sniff and try to work out what the issues are. How are these people living their lives? Why has it failed? Everyone is still spending. They might be spending less, but they are still spending."

The Kent seaside town is emblematic of the problems our high streets face. A survey in February 2011 showed it had the highest proportion of empty shops in the country: 37.4%. Across Britain, one in seven shops is now boarded up, as consumers drive to out-of-town malls or wait out the recession with their hands in their pockets. Then there is the one-click efficiency of online shopping: the UK is Europe's leading e-retail economy, with sales estimated at £68.2bn for 2011; the market grew 16% in 2011 and is predicted to increase by a further 13% this year. That is why high street chains such as Woolworths, Zavvi and Habitat have made way for an endless parade of mobile-phone stores and charity shops.

In December, the Portas Review outlined 28 recommendations that range from the creation of a new National Market Day to lowering the cost of town-centre parking. Hundreds of towns have applied to become a Portas Pilot Town, one of 12 towns that will share a £1m "golden ticket".

"What will be the future?" asks Portas. "It's not just, 'Here's a report,' but what can we do about it and what will be the new business model for high streets? For me, as a retailer, this is where the sexiness lies."

The artist: Martin Boyce

The idea: turn high streets into urban playgrounds

I was in New York recently and every morning I'd walk to the gallery along the High Line. It's a park that opened in 2009 along a post-industrial railway line – an elevated, landscaped walkway. You have a completely different relationship with the city: instead of dodging cabs, you glide through it on this lawned escalator.

We think landscapes only exist out of the city, but the High Line is proof they don't have to. We should give high streets over to landscape architects more than retailers. I would like to see town centres become like huge gardens or playgrounds. Give it to the skateboarders and BMX kids – the people they shoo away from these areas – because these are the people who actually know how to use urban areas. We should embrace the dynamism that they bring.

Manhattan is a special situation, but there are things we could learn from it. The High Line was designed by a British landscape architect, James Corner, and he was into the idea that it shouldn't look overly designed: plants die and others come up to replace them – it's a wilderness, really. There would be something surreal and magical about ripping up the tarmac in a run-down town centre and putting down a wild, overgrown lawn.

The high street needs to embrace everyone. I would like to see older people moving back into the centre. You could pop out and meet your friend, sit on a bench and watch skateboarders. We would be surprised by the sense of community that would develop between the different age groups: you saw it in the riots around London, when people were out cleaning up and putting things right.

So much architecture is about trying to repel the undesirable: benches you can't sleep on, doorways you can't sit in. You need those dark, dirty corners that allow for the unexpected. You need uncertain gaps that let not necessarily just young people, but anyone re-energise. If everything's planned you are in the hands of the planners.

The high street, as we nostalgically think of it, is gone. It's dead. But for me there's still hope and optimism. It's about finding the poetic or magical qualities within the everyday.

Martin Boyce is the winner of the 2011 Turner Prize

The retailer: Jane Shepherdson

The idea: offer lower rents to attract new British talent

About two years ago, Whistles was invited by the landlords who own most of Covent Garden to look at their plans for the area. At that time, if you lived in London, you wouldn't really go down to Covent Garden: it was old scrappy shops full of tourists and the market didn't quite know what it was doing. But the landlords showed us what they wanted to do: the covered market was going to be for small perfume and jewellery stores; there would be an outer ring of prime real estate for stores like Apple and Burberry; fashion would be down Long Acre. They were going to bring in a big restaurant from New York, Balthazar, and a boutique hotel. They had a brand director whose job was to attract the right mix of brands for the right parts of the scheme. It was an amazing plan.

Town planning is so important – why would you not do it? These people are not doing it because they want Covent Garden to look lovely. They are investors securing their investments for the future. They are making sure their land becomes valuable because Covent Garden is so wonderful. It's the difference between taking a long-term view and a short-term one and it's what our high streets need.

There are a number of factors that are having an impact on our high streets now. Certainly the recession is one of them, no question: people are going out of business because there isn't as much money in the system. There's also online shopping, which is of course taking some of the spend away and forcing retailers to close shops.

But not everywhere is suffering equally. We are noticing that where there is a very pleasant village-style environment – where people in their leisure time will wonder around with a coffee with their kids, popping in and out of shops, getting fantastic service, having a little chat with the staff who they know quite well – these places are prospering. This is the reality of shopping: if it's not a pleasant experience, why would you go out and do it? You will just buy those things online.

I'm surprised that town planners are not more involved in our high streets. In any other industry you have a strategy: "Where do we want to be in five years' time?" It could be that you need to reduce the rents and actively target interesting independents and coffee shops to introduce a bit of variety. Landlords need to get real, too. Right now the only retailers who can afford the rents are phone shops, which is not great for your average customer and it's not sustainable either.

We certainly have the talent in Britain. Just look at the fashion industry: in the last few years we've home-grown global stars like Christopher Kane, Erdem, Peter Pilotto, Mary Katrantzou, Jonathan Saunders. What's happening now is that they are all going online because there's almost zero expense and no risk. But if there were more opportunities for them to showcase their skills, it would make the high street more exciting for all of us.

Jane Shepherdson is chief executive of Whistles

The architect: David Adjaye

The idea: bring public buildings on to the high street

For years, planning law has been against the culture of the high street. The regulations have been overly draconian and the agenda was close-minded. They wanted to preserve the townscape as some wonderful picturesque "glossy Victoriana", which is out of touch with what these environments need to be. These are very transitory spaces and planners have stopped a lot of incredible creativity happening in these places.

I'm not saying that we turn our high streets into crazy versions of Las Vegas. We don't need to put lights everywhere to attract customers. But there has to be an understanding that the high street is an evolving model and it requires a planning law which is flexible.

It's not just about making funny-looking, showy buildings either. I always love the Apple Stores. These are not showy, but they create a fantastic quality of experience that means people just want to hang out there – that's why they are full all the time. You can browse on their machines for free, but there are lots of places – like Dixons or wherever – where you can browse for free and people don't hang out. At the lower end, you think of Starbucks. The reason Starbucks is so popular is that it genuinely makes a living room for people who don't have one, like students. Even McDonald's has copied the Starbucks model by putting designer sofas in their fast-food joints.

There is obviously a crisis in retail at the moment, but I find that very exciting. In the early 2000s, Adjaye Associates was commissioned by Tower Hamlets in east London to rethink two of their public libraries: in Poplar and on Whitechapel High Street. The big complaint about the old libraries was that they were not connected to the economic activity of people. They functioned best when they right there and convenient, and became remote and less desirable when they were away from that.

On Whitechapel High Street, we put the library – called the Idea Store – right in the middle of the mom-and-pop stores, right by the market. I decided there would be no doors, no grand staging: this was going to be as easy as walking into Marks and Spencer. You don't go into a hermetic interior where everyone is talking in hushed voices – it was almost as if you passed from the betting shop into the library and went to get a cup of tea.

We hoped for a two-fold increase in visitors, but immediately there were four times as many. The whole idea that libraries are dying and people don't want to go to them – it couldn't be more the reverse. Strangely, the Idea Stores have been taken up all over the world – Sweden, Germany, America – but there still seems to be a suspicion of it in Britain.

I'd like to see more public buildings on the high street. Council activity should not be in rarefied big blocks like the town hall. People should be able to engage with it very directly and we don't need big buildings to do that anymore.

David Adjaye is principal architect of Adjaye Associates

The fashion magazine editor: Lorraine Candy

The idea: create a lust for bespoke shopping

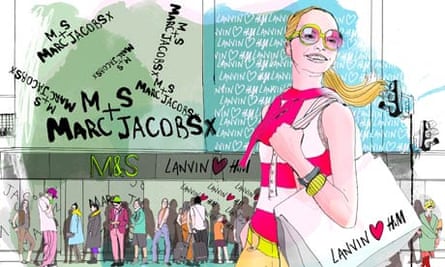

When H&M launched their collaboration with Versace last November the first person started queuing outside the Regent Street store at 4.45pm the day before. It was a similar story for the range it created with the Italian label Marni last month; the queues were around the block, lots of people camped out overnight. You hear a lot of tales of woe from high-street retailers, but this is one example of a company being very clever. H&M's first guest designer was Karl Lagerfeld in 2004, and it has done collections with Stella McCartney, Commes des Garçons and Lanvin. The pieces are limited, they are not available for the whole season and it really creates a frenzy. It's become part of the fashion calendar now. Who will H&M ask next?

One of the things that I've always felt about fashion on the high street is that retailers need to look at a more bespoke offering. While you can buy everything online, you need to offer something – a specific range or an experience – that you can only get in the shops. Then, once you have the customer in the store, you need to walk her round so she buys more than the special things she's come for.

The look of the store is absolutely crucial. It's about being that place that everyone wants to be; you need to create that lust. You see that at the top end when Louis Vuitton does an amazing window display with a very famous artist: you're going into an art gallery as much as you are going into a shop to buy something. Inside the store it is vital to create a distinct brand identity. This will be different for everyone: Reiss always makes their shops look incredibly beautiful, stylish and upmarket; there's always a lot of space between the hangers so the clothes are easily viewed. In Next, they fill in as much space as possible to say here's as much choice as possible.

Shopping online is always going to be huge, but the great hope for the high street is that nobody wants to stay indoors the whole time. For young women, a lot of their social life is based on being outside with their friends – shopping is always going to part of it. You have to view it in a positive way: online can drive people into shops; you've got this whole audience via social media and you can reach them at any given point in their day.

What really impresses me about fashion on the British high street is that it works really hard to be wantable. They rotate their stock every four to six weeks and can respond very quickly to new trends. Something like Mad Men: it's on TV for a couple of months, it's a very definitive fashion statement and the stores are always very reactive to that.

When businesses are in recession and margins are decreased, fashion has to be very quick at coming up with new ideas and new ways of making it work – fortunately, it's a very creative industry, so people are very creative around it.

Lorraine Candy is editor-in-chief of Elle

The philosopher: Alain de Botton

The idea: make psychotherapy like a visit to the hairdresser

For centuries in the west, there was a figure in society who fulfilled a function that is likely to sound very odd to modern secular ears. He (there were no she's in the role) didn't sell you anything or fulfil any material need, he couldn't fix your ox cart or store your wheat, he was there to take care of that part of you called rather unusually "the soul", by which we would understand the psychological inner part, the seat of our emotions and sense of deeper identity. I'm talking about the priest, the stock figure of pre-modern western life, who would accompany you, from earliest infancy to your dying breath, attempting to make sure that your soul was in a good state to meet its maker.

Because in many western countries, the priesthood is now a shadow of its former self, a key question to ask might be: where have our soul-related needs gone? What are we doing with all the stuff we used to go to the priest for? Who is looking after it?

My suggestion is that therapists should be secular society's new priests. From a distance psychotherapists look like they are already well settled in the priest-like role and that there is nothing further to be done or asked for, but there is, in a serious sense, an issue of branding here. Therapists are hidden away. You don't see them on the high street. They still aren't regulated as they should be. We don't make a place for them among other needs like those for bread or electrical goods. Imagine if the need for therapeutic dialogue was as honoured and recognised as the need for a haircut or a go on an exercise machine. Imagine if seeing a therapist wasn't a strange and still rather embarrassing pursuit. Imagine if one could be guaranteed a certain level of service. Imagine if the consulting rooms looked better and were more visible, to make a case for the dignity of the activity.

Therapy remains a minority activity, out of reach of most people, too expensive or simply not available in certain parts of the country. There have been laudable efforts on the parts of activists like Lord Layard to introduce therapy into the NHS, but progress is slow and vulnerable. But the issue isn't just economic. It's one of attitudes. Whereas Christian societies would imagine there was something wrong with you if you didn't visit a priest, we tend to assume that therapists are there solely for moments of extreme crisis – and are a sign that the visiting client might be a little unbalanced, rather than just human.

To survive, the high street will need to focus on all the things that cannot be done online – which chiefly means, things that involve the body or the social self. So restaurants will survive, as will anything that involves community. Moving psychotherapy onto the high street seems a natural progression. It means recognising that the high street is a natural place to take care of psychological needs that were previously attended to out of sight. Consulting a therapist should be seen as no less normal than going to a nail bar and a lot more useful.

Alain de Botton is a founder of The School of Life, and author of the recently published Religion for Atheists

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion