Does Apple have a backdoor that it can use to help law enforcement bypass your iPhone's passcode? That question became front and center this week when training materials (PDF) for the California District Attorneys Association started being distributed online with a line implying that Apple could do so if the appropriate request was filed by police.

As with most things, the answer is complex and not very straightforward. Apple almost definitely does help law enforcement get past iPhone security measures, but how? Is Apple advising them using already well-known cracking techniques, or does the company have special access to our iDevices that we don't know about? Ars decided to try to find out.

The document

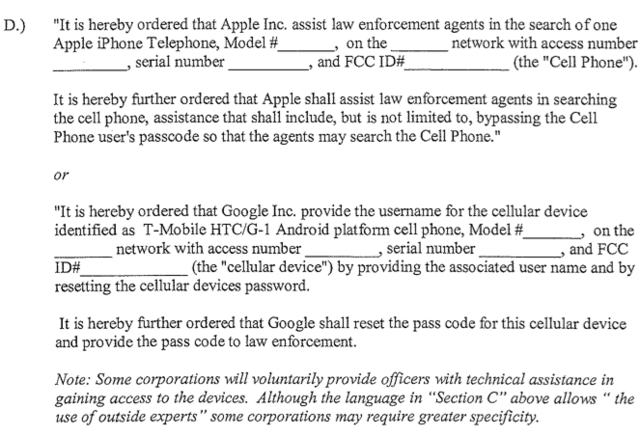

The training material in question is relatively innocuous when taken on its own. On page 25 of the massive 189-page PDF, the District Attorneys Association provides two templates for serving both Apple and Google with requests for assistance in accessing a suspect's cell phone.

"It is hereby further ordered that Apple shall assist law enforcement agents in searching the cell phone, assistance that shall include, but is not limited to, bypassing the Cell Phone user's passcode so that the agents may search the Cell Phone," reads the document.

Security researcher Chris Soghoian was the first to tweet about the curious language that implied Apple could bypass a user's passcode at the request of law enforcement. Soon thereafter, a source confirmed to CNET that Apple has been lending assistance in passcode bypassing for the last three years. But the CNET report doesn't answer the central question: does Apple have an actual backdoor for this, or is the company just helping to point investigators in the right direction?

The way things were: 2010 edition

There's at least one caveat to consider before diving into this question: the fact that the document was distributed in March of 2010, when the iPhone 3GS was the most current iPhone and iOS 4 had not yet been released to the public. At that time, bypassing a user-defined passcode or four-digit PIN "was trivial even without Apple's assistance because a passcode was not used to encrypt anything; it was merely a UI protection," Olga Koksharova of information security firm Elcomsoft told Ars.

And brute-forcing a passcode or PIN of that length isn't a difficult task for an experienced researcher or dedicated hacker (a simple 4-digit PIN would take a maximum of 18 minutes to guess on the device, for example). "All the forensics tools companies have deep ties to law enforcement, and push their ability to perform forensics on iPhones. Those tools (today) need to brute-force the passcode," Securosis CEO and TidBITS Security Editor Rich Mogull told Ars. "This wasn't always true, and especially before the iPhone 4S there were techniques to get around the passcode and Data Protection."

Those techniques, on the simplest level, involved jailbreaking a device to get around the PIN/passcode. And in 2010, iOS devices had no data encryption to go along with the other security measures, so law enforcement likely had no trouble at all accessing data on a suspect's iPhone with or without Apple's help.

But what about today? "There are current techniques to circumvent the passcode, but these won't give you access to anything secured with Data Protection," Mogull said. With the release of iOS 4, Apple gave users the ability to encrypt some of the user data stored on the iPhone when the user sets a PIN or passcode. The result was that even when law enforcement or an attacker was able to jailbreak the device, the data remained under lock and key. So at the very base level, the 2010 document may have been referring to hacking techniques that are no longer directly relevant for dealing with today's Apple devices.

Pointing law enforcement in the right direction?

Regardless of what was possible in 2010, Mogull strongly believes that today, Apple is merely advising authorities using already well-known security techniques and doesn't have its own backdoor through the device's PIN or passcode.

"Apple is probably limited to the same techniques based on what I know of the security model. So those newer devices are still protected (probably, until someone releases an exploit) even with Apple helping out," Mogull told Ars. "Thus I think the document refers to asking Apple for help using known techniques."

But Koksharova disagreed, indicating that she believes Apple could get around a user's passcode in ways that traditional forensics tools can't. "Apple has keys to sign custom bootloader, kernel, and tools—this means no exploit is needed to load forensic tools onto the device," Koksharova told Ars. "Currently all (non-Apple) forensic tools work by exploiting some vulnerability on the device to bypass code signature enforcement; this is the reason why iPad 2 and newer devices are not supported in those tools—there are no known vulnerabilities on those devices. Apple is not subjected to the same limitations, obviously, and can support any device."

In addition, Koksharova pointed out that Apple might have access to an iDevice's unique device key, which is embedded within the device itself and used as part of the device's local encryption/decryption key. (Read more about how this unique device key is used as part of an iOS device's AES cryptographic accelerator to encrypt data in this iOS 4 security whitepaper by Trail of Bits, starting on page 27.)

"Apple probably knows all those keys for its devices and thus can perform [the brute-force process] offline (off the device), possibly yielding much faster passcode recovery speeds (10x-100x faster, I'd guess)," Koksharova said. "I do not know if Apple actually does this, but technically they certainly can."

Possible but unlikely

Security researcher and repeat pwn2own champion Charlie Miller agreed that it's possible for Apple to have done this, but also thinks it's unlikely.

"On the one hand, Apple made the software and could do whatever they wanted, if they really wanted to be evil. They could record the passcode when you enter it, ship the passcode off to Apple servers for storage, store/export the encryption key, etc.," Miller told Ars. "However, there is no evidence that they have ever done anything like this, and if they did, it is likely that myself or other researchers would have noticed by now. So if you discount that conspiracy theory, you have to assume they don't have your passcode and can't get it."

But, Miller said, Apple may have a record of your device key—"nobody knows if they store these keys or not," he said.

If Apple does keep device key records, they could be given to law enforcement for a faster brute-force session off-device. "It is pretty much impractical to break a six-character passcode on the device itself, but may be entirely practical offline using specialized systems. So to me it seems like it might be possible for Apple to help [a law enforcement official], but not directly, if they really store these hardware keys, but again, nobody knows if they do that or not," Miller said.

Data Protection and beyond

Apple declined to comment on iPhone security for this story, so we were unable to confirm whether the company has these abilities or uses them to help law enforcement. But assuming that Mogull and Miller are right—that Apple doesn't have its own backdoor or isn't making use of it—that leaves the data that is encrypted behind the PIN/passcode.

As we recently discovered, Apple holds the key to encrypted iCloud data on its own servers—if law enforcement sent the appropriate subpoena, the company can easily decrypt your cloud-stored data and send it off to the authorities. Could this apply to the iPhone too? It seems the answer is no: both Mogull and Miller pointed out that an iPhone user's data under Data Protection is encrypted using a key that is derived from the user-set PIN/passcode, and if no one knows what the user has chosen, it will be very difficult to crack the key. This makes it different than iCloud, where Apple ultimately holds the encryption key for any data stored there.

"On the device it's very different. Data Protection works by encrypting the data with a passcode only known to the user," Mogull said. "Unlike with iCloud, Apple doesn't have this. You have to brute-force it. Unless Apple is lying their asses off about how it works, there should be no way they can get past it," Mogull said.

That doesn't mean it would be difficult for the police to dig into your digital life. "Keep in mind that a lot of data on an iDevice isn't protected with Data Protection," Mogull pointed out. "And some (like photos, calendar, contacts) don't appear to be protectable since multiple apps have access to it."

So what's the answer to the central question? Does Apple have a secret backdoor to hand over your passcode to authorities? The general consensus among our experts was "probably not." Does Apple assist law enforcement in their attempts to crack your PIN/passcode using methods the security world is already aware of? We'd be surprised if they weren't. And can law enforcement, with enough time and effort, brute-force their way past your passcode? The experts we spoke to gave a resounding "yes," though the level of effort required will coincide with the complexity of your passcode and how bad they want the data.

Listing image by Photograph by Aurich Lawson

reader comments

71