Splat Science: Fossilized Raindrops Reveal Early Earth's Hazy Skies

It was raining 2.7 billion years ago. That's according to imprints of raindrops discovered in ancient rock in South Africa. Those same weather marks are giving researchers a clearer picture of what Earth's early atmosphere was like.

Back then, the sun was about 30 percent dimmer, giving off less heat, which suggests our planet should have frozen over. As for why it didn't, and why rocks show evidence of abundant water as far back as 4 billion years, scientists have suggested a much thicker atmosphere, high concentrations of greenhouse gases, or a combination of the two kept early Earth toasty.

"Because the sun was so much fainter back then, if the atmosphere was the same as it is today the Earth should have been frozen," study researcher Sanjoy Som, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center, said in a statement.

The new results suggest an atmosphere full of strong greenhouse gases, like methane, at the time helped keep the Earth warm instead of becoming an icy Hoth-like planet.

Early Earth

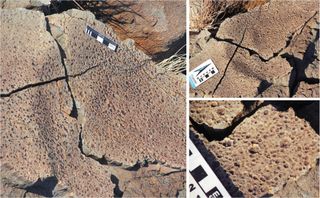

The impressions of raindrops were preserved in ancient volcanic ash that later fossilized. To learn more about the atmosphere from which these ancient drops fell, Som, who was a graduate student at the University of Washington at the time, and his UW colleagues needed to figure out how fast they were coming down.

In today’s atmosphere the biggest raindrops, which can be a quarter-inch wide, fall about 30 feet per second (about 9 meters per second). A thicker atmosphere would put more drag on the raindrops, lowering their speed, meaning the same-size raindrops would leave smaller imprints.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So the researchers compared the fossilized raindrop imprints with ones they created under the force of today's atmosphere, using different amounts of water and a substrate similar to what they think existed back then — recently fallen volcanic ash from Hawaii. [50 Amazing Facts About Earth]

Based on the size of the imprints, the researchers were able to say that the atmosphere that created the ancient raindrops was no more than twice as thick as today. But because the largest possible raindrops are extremely rare, Somsaid the imprints were probably created by somewhat-smaller-than-max-size drops. That suggests the pressure was the same, or even lower, than it is today.

The results favor a buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as the explanation of why Earth was warm.

Other orbiters

Som said the finding could prove important in the search for life on planets orbiting other stars, called exoplanets. "Today’s Earth and the ancient Earth are like two different planets," yet early Earth supported abundant life, too, in the form of microbes, Som explained.

"Setting limits on atmospheric pressure is the first step towards understanding what the atmospheric composition was then. Knowing this will double the known data points that we have for comparison to exoplanets that might support life," Som said.

The study was published today (March 28) in the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Most Popular