Jupiter Still Has Water from 1994 Comet Crash

The stratosphere of Jupiter is filled with water delivered to the giant planet by a cataclysmic comet crash in 1994 that not only wowed scientists at the time, but spawned a legacy that is still delivering surprises today.

In July 1994, more than 20 broken-up pieces of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 slammed into Jupiter, captivating skywatchers and scientists alike.

Now, new research reveals that the comet collision not only gave Jupiter scars big enough to be seen from small telescopes on Earth; the ice-filled comet also dropped loads of water onto the atmosphere of our solar system's biggest planet, scientists say. [See photos of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 hitting Jupiter]

Water vapor was first spotted in Jupiter's upper atmosphere by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Infrared Space Observatory in 1997. The spacecraft also found similar traces of water in the atmospheres of Saturn, Neptune and Uranus.

On Jupiter, scientists knew that it could not have floated up from the inner part of the atmosphere because there's a vapor-blocking "cold trap" that separates Jupiter's stratosphere from the clouds in its troposphere below. But researchers remained unable to say where exactly the water came from.

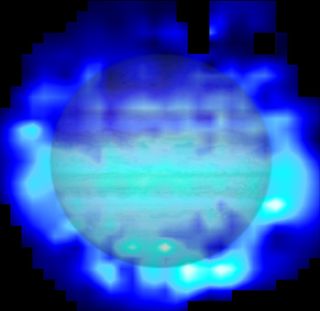

Using ESA's Herschel space observatory, the most powerful infrared telescope ever sent into space, scientists recently mapped out the distribution of water vapor in Jupiter's upper atmosphere. They found that Jupiter's southern realm, where the comet hit, had two the three times more water than the planet's northern hemisphere. What's more, most of the water vapor was clustered around the Shoemaker-Levy 9 impact sites.

"The asymmetry between the two hemispheres suggests that water was delivered during a single event and rules out icy rings or moons as candidate sources," study leader Thibault Cavalié, of the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, said in a NASA statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"According to our models, as much as 95 percent of the water in the stratosphere is due to the comet impact," Cavalié added in a statement released by ESA.

These observations led Cavalié and colleagues to rule out other possible sources of the water vapor, such as a steady rain of interplanetary dust particles, which would have spread the vapor more evenly across the planet's upper atmosphere.

"All four giant planets in the outer solar system have water in their atmospheres, but there may be four different scenarios for how they got it," Cavalié explained. "For Jupiter, it is clear that Shoemaker-Levy 9 is by far the dominant source, even if other external sources may contribute also."

The research is detailed in the May issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.