At 10 to five one Saturday afternoon last year, I was walking up the Hornsey Road in London with a tin of rhubarb from Tesco, checking the football results on my iPhone after a lovely day at Kew Gardens. The phone replaced the BlackBerry I'd destroyed a month earlier by running into the sea to save my daughter from drowning.

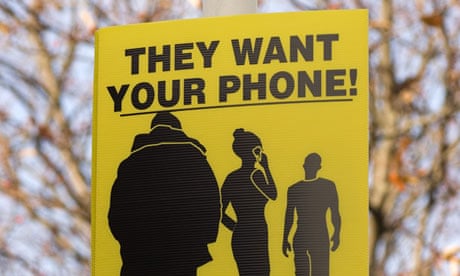

Behind me on the pavement I heard a motorbike and, thinking the rider was going to park, carried on holding the phone in my left hand and scrolling with my right index finger – that fey, giveaway gesture of iPhone users. Over my shoulder the right arm of the bike's pillion passenger appeared and snatched the phone. The bike was 200 yards away before I composed myself enough to look for the registration plate or think about clubbing the thieves with canned fruit – it was a seamless snatch from a soft target. And a common one. The Guardian reported last year that in my borough (Islington) there was a 400%-plus increase in phone snatches between 2010 and 2011. Detective Inspector Karen Gilmour, head of Islington police's robbery unit, was quoted in the local paper recently saying: "It seems to me they can make an assessment very quickly as to whether the person they're looking at has got the sort of phone they want." She said that most stolen phones are immediately switched off, the sim card removed, and the phone passed on to handlers who ship them abroad for as much as £600.

Of all the minor unpleasant incidents I've suffered – bus stop shovings, that time I unwisely confronted a disturbed dog owner about letting his pit bulls run wild in the toddlers' sandpit, the interview during which Robert de Niro called me a "fucking wise guy" – none had as intense a physical, nor as enduring an emotional, effect. I felt winded even though I hadn't been touched. I plodded home hyperventilating, thinking grimly about my neighbourhood – drug busts in the park, a fatal stabbing outside the chip shop, my partner's sister beaten black and blue on this same street the year before by three boys for whom punching a woman until she lay flat on the pavement was a summer evening's entertainment.

At home, I called the phone company, whimpered to my partner, and my seven-year-old made a collage of autumn leaves with the inscription: "To Daddy, love Juliet. PS: I am sorry about your phoun [sic]". Meanwhile, the kids who had stolen my phone had crashed their bike during a police chase and the driver had been arrested. Later police caught the boy who had snatched my phone, conspicuous because his jeans were ripped from the crash and he was wearing only one trainer.

My partner's phone rang half an hour after the theft. "We've got your phone," a sergeant told me. "Think yourself lucky. Hardly ever happens." A few days later I picked it up from a police station covered in finger-print dust.

Six months later, I was on a train to meet the boy. In March, after pleading guilty to several counts of theft and robbery, the boy was given a youth rehabilitation order, one of whose conditions bans him from London for six months. What did I want from the meeting? I wanted to see the thief. I spent a lot of time imagining the woeful life that would lead him to become so adept a thief. I was a victim certainly, but a privileged one. Even if I hadn't got my phone back, I'd have been able to buy another; moreover, I now feel more circumspect in my neighbourhood – in that, the theft was a usefully chastening experience.

At the Youth Offending Team offices in Chatham, Kent, I shook the hand that had snatched my phone. A 16-year-old black British boy in hoodie and jeans, uncomfortably hot in this airless room. He told me he was a boxer, whose mum had aspirations for him to make it as a heavyweight. What if I'd held on to my phone? Would he and his mate have beat me up? If so, doubtless, I wouldn't be feeling so benign now.

What did he want from the meeting? "To say sorry," he said. This, said the victim liaison officer who arranged the appointment, was a "restorative justice meeting" at which the victim could say how the crime had made them feel and the criminal express regret to the victim for what they had done. None of his other victims wanted a face-to-face meeting, least of all, perhaps, the 34-year-old woman who had hung on to her phone, was knocked to the ground and dragged along the pavement suffering scrapes and bruises before she finally gave it up. Did she feel, as I do, like a privileged victim? Unlikely.

We (him, his case worker, a victim liaison officer, me) sat down and turned off our phones. "This is the one you stole from me," I laughed. "I am sorry," he said. He said so repeatedly. I complimented him on the professionalism of the theft. But what if it had gone wrong? "I never thought about it at the time. But I should have – we crashed a few minutes later." What about hurting his victims? "I didn't set out to hurt anyone."

Why did he do it, I asked. He told me that since his parents had split up he had felt as though he had to be the man of the family and provide for his mother, who lives on benefits. I said that sounded like a story he might tell afterwards to feel nobler about robbing people in the street.

If his dad had been at home rather than living with a new wife outside London, he said, he probably wouldn't have become a criminal. It was his dad who laid down the law. It's a huge social problem, I said, only later thinking – what do I know of it? I'm not from a broken home. At 16, I was revising for O-levels, not meeting my crime victims with school years a wasteland behind me.

Diane Abbott MP asked during a Commons speech last year about black and ethnic minority achievement: "Why do black children fail?" The answer, she said, "is partly to do with poverty in an absolute sense, although all the research shows … black children systematically do less well than children of other ethnicities. There is no question but that poverty is an issue. Nowadays there is also increasing peer-group pressure." Such peer pressure was a factor in this case. Earlier that day, the boy told me, he had two choices - go to boxing training or go on the rob with his friend as he had done before. He chose the latter.

Peer pressure isn't the whole story. Abbott spoke of black boys "who throughout their education have engaged only with women and have never seen a man as an educational role model. More male teachers are important." He told me he hadn't done well at school, couldn't concentrate – again hardly a surprise. Abbott said: "If we abandon a cross-section of the community in our inner cities, they have a way of bringing themselves back into the political narrative – a way that is not good for them or for society." That, maybe, is what happened one dismal evening on the Hornsey Road.

The victim liaison officer asked how I felt after the theft. Wary, I said, careful not to use my phone in a dodgy neighbourhood (such as, it turns out, the one in which I live). "You shouldn't have to think like that," said the boy, shaking his head. "You should feel OK using an expensive phone in the street." But thanks to him I'm not. It was about the only time during the interview where I got cross. I think he was disappointed that I wasn't more angry during our hour together. If so, good – I didn't want to give him the satisfaction.

Rather, I wanted to give him something worse, crueller even – pity. He suffered much more than me, I said repeatedly. I showed him my daughter's drawing as if to stress how loving and solid a family I have. A low blow. He told me about his family – how furious his mother had been, that his dad was so angry he wouldn't visit him in jail, how his nan was ashamed of him. He told his nephew that the thing he has around his leg is a hi-tech watch – just so he doesn't learn his uncle's a tagged criminal. I felt sorry for his mum, who couldn't come to the meeting, for his dad, who wouldn't, and – a little – for their son.

The order bans him from going inside the M25 for six months. It means he can't see his mother, unless accompanied by his case worker. He now lives with his dad in Kent.

At court, he readily accepted the terms of the order rather than go back to Feltham Young Offenders' Institution, where he'd already spent a month, to serve an 18-month sentence. In Feltham, he said, he was OK because he knew gang members who could protect him. But their protection was a double-edged sword – it meant he would still associate with people who might lure him back into committing crimes. The order, then, gives him a chance to remake his life in a way that jail may not have. He's away from gangs, away, perhaps, from greater risks of recidivism. He attends boxing training and in September goes to college to train as plumber or mechanic.

As the case worker drove him back to his dad's house to fulfil his curfew, I returned to the city from which he is banned, thinking about this boy, both victim and perpetrator of the crime. He said he would write to me and when he does, I hope he'll tell me he's doing something worthwhile with his life, because it doesn't do either of us any good for him to remain what he is to me now, an object of pity.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion