Using your 'inner bat' to help navigate

- Published

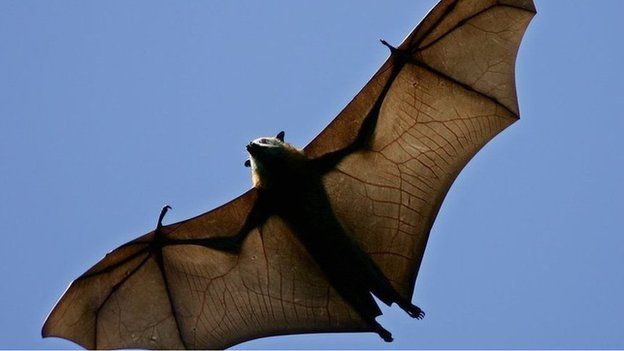

Bats are famous for using sound to navigate successfully, and new research suggests we could all use our "inner bat" to get around.

Blind people are aware of this technique. Some click their tongue or tap their cane on the floor and use the resulting echoes to help them move around safely.

Researchers in Southampton have found that we could all make use of the soundscapes that surround us, whether we can see or not.

The new study, which involved both sighted people wearing blindfolds and blind people, considered the types of sound that worked best to locate an object.

Lead researcher Dr Daniel Rowan, a lecturer in audiology at the University of Southampton, said in one test the longer sounds, lasting around half a second, made things easier.

"What the experiment showed is that as the duration of the sound got shorter and shorter, people's ability to tell whether an object was to the left or right got worse. Having a longer duration signal appears better than a short one."

But if you want to know something different about an object - like how close it is - it may be that a shorter duration, of just 10 milliseconds, could be better.

"Some bats that use echolocation. If they're hunting prey, they change their call as they get closer to the prey to reveal different sorts of information."

Never crash

Claire Randall, who has been virtually blind from birth, uses echolocation.

"I think the first time I was aware of it was when I was about five. I used to ride a bike and I developed the ability to swerve past a lamp post and miss it by millimetres, too regularly for it to be a coincidence."

Her mother marvelled at her ability to miss obstacles.

"One day my mum asked me how I always managed to miss the lamp post, and the only way I could explain it was, 'It goes dark past my ears.' "

The history of echolocation is fascinating. Back in the 1940s and 50s there was an idea that we had a separate sense on the face specially for detecting echoes.

Now we know it's the hearing system that does it and, although blind people seem to have honed their skills, we are all capable of navigating using sound.

One reason sighted people may not exploit this ability so much is that their world is dominated by vision.

This is seen in the "ventriloquism effect", where sounds are attributed to a dummy because its mouth is moving, overriding where the sound is really coming from, the poker-faced ventriloquist.

Previous research has involved real-life locations. But this study used "virtual obstacles", represented by sounds mimicking echoes from those imaginary objects in headphones worn by the study participants.

Extraordinary feats

Dr Rowan said: "In using virtual objects there were no other clues that someone might use: for instance, the creaking as you move an object around or the wafting of air across their face as you move something around."

He has heard the reports of extraordinary feats.

"There are some expert echolocators who are able to do some fairly amazing things, such as ride a bike or play basketball, and World Access for the Blind trains people to do this.

"But we know less about how blind people in general use echoes."

The findings have just been published in the journal Hearing Research. Dr Rowan hopes that they will help to improve echolocation skills.

He said: "One of the things we wanted to try to contribute to with our research is to provide some underpinning science that may help the development of training programmes, to help blind people use echoes that arrive at their ears more effectively.

Hugh Huddy, from the charity VISION2020UK, said: "This research study is important because not enough is known about the way blind people utilise sound to get around, or indeed how people in general are able to hear the world.

"The link with bats is not helpful though. If this study leads to a better understanding of the amazing yet ordinary hearing abilities within everyone, this may help blind people to make the most of their hearing.

"If scientists can provide answers to big questions like does hearing improve when eyesight becomes impaired, how do blind people develop their hearing skills, and are streets safer for everyone when they are designed for hearing as well as seeing, then there are exciting possibilities for the future."