They were grim days which called for tough action: President Obama had just signed an $800bn economic stimulus package into law, Wall Street had sunk to its lowest level in 12 years and America's carmakers had just asked for a total of $39bn to prevent them going bankrupt.

Japan had just recorded GDP falling at a shocking 12.7% as demand for cars and electronics dried up and Britain was plunging into recession.

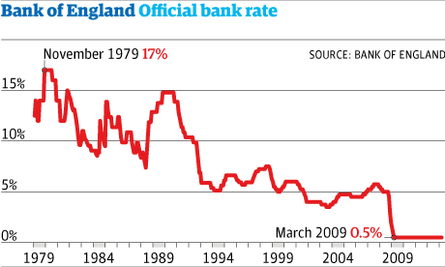

It was against that backdrop that the Bank of England's monetary policy committee (MPC) decided on aggressive action. They slashed interest rates to a record low of 0.5% and decided to print money, using £75bn worth of quantitative easing (QE) in an attempt to head off a damaging slump. Few considered then that the economy would still be in the intensive care ward years later, with £375bn of QE pumped into the economy, the same low interest rates and no real signs of growth.

On 7 March 2009, It is four years since the introduction of the ultra-low interest rate strategy was introduced – and Britain's economy remains stuck in first gear.

Senior figures at the Bank of England are unlikely to mark the anniversary with any kind of celebration. Instead, their search for more effective ways to make cheap money available for first-time homebuyers and small- and medium-sized companies will continue.

Members of the central bank's monetary policy committee, concerned that growth remains fragile and slow enough for output to stall or go into reverse, are expected to use their third meeting this year – the 45th since the financial crisis began – to inject another £25bn of fresh funds into the system using QE.

Plans to adopt more exotic schemes may be announced this year or next. But, in the meantime, QE is the chosen method of governor Sir Mervyn King and, according to deputy governor Paul Tucker, all nine MPC members.

King voted for another £25bn of QE at the last MPC meeting, along with two other committee members, and is expected to maintain his stance . Economist and former MPC member David Blanchflower believes they will go further and vote for £50bn.

Blanchflower points out that unemployment remains stubbornly high and, without some dramatic fall, he believes there will be lasting damage to the skills base of the economy.

Chris Williamson, chief economist at financial data provider Markit, believes the decision is more finely balanced after some signals that the wheels of the economy might be beginning to get some traction. Analysts at Capital Economics reckon encouraging data "has probably tipped the balance in favour of the status quo".

The low interest rate strategy, often used to encourage a higher level of borrowing in times of recession, has failed in its task, according to figures out this week. The Bank of England's own lending data showed a £2.7bn contraction in the value of loans to businesses and mortgage buyers in the final three months of 2012.

State-owned banks Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds were chiefly to blame after they more than offset an expansion in lending by Barclays and several building societies.

Ros Altmann, a governor of the London School of Economics, reckons the strategy has failed in other ways. She has waged a campaign against the Bank of England's policies for several years, arguing they hand a benefit to people who are putting saving before spending.

Indeed, the central bank's own report shows much of the benefit of QE has gone to the banks and the top 5% of earners, who own shares and property that would have crashed in value without QE.

Savers have also suffered a sharp decline in rates, with many deposit accounts struggling to get above 1%.

"Although mortgage holders have done well, they have not rushed out to spend the extra money they have each month," says Altmann.

"Many have merely accelerated their mortgage repayments to pay down their loans faster, because they had over-extended themselves to buy their properties. The benefits of lower rates have, therefore, not fed through to growth as would be expected, while those who do not have big debts have suffered falling incomes as rates decline.

"Older savers, who had expected to be able to live on income from their savings, have been particularly hit since 2008. This helps explain why the policy of low interest rates has not generated a recovery, since those who do not have large debts have seen their incomes fall and have cut spending."

Capital Economics, one of the gloomiest independent analysts about the prospects for the UK economy, suggests Altmann will be campaigning for some time to come. It reckons interest rates could yet go lower, and that QE might rise to £500bn by the end of next year: "We doubt base rates will rise before the second half of 2015 at the earliest and think that some sort of rate cut is more likely than a hike within the next two years.

"It's easy to forget that when the rate first fell to 0.5%, it was widely expected to stay there for only a short while. Markets expected rates to rise in early 2010 and to have risen to more than 3% by now. And the consensus forecast of economists was for rates to have risen to nearly 4% (and for QE to reach only a total of £150bn). But investors and economists revised their interest rate predictions as the economic recovery persistently disappointed their expectations," it said.

For home-owning, mortgage-paying middle income families, the cut in base interest rates to 0.5% four years ago is the single biggest factor preserving their living standards through the economic downturn.

Two recessions have come and gone and a third may be on its way, while wage increases are low, inflation is high and welfare benefits are about to be cut drastically.

However, access to mortgage rates of 3.5% or less has allowed millions of people and businesses to pay down their debts at an accelerated rate. The stock of outstanding mortgages is lower than in 2007 and businesses have cut back on overdrafts and loans.

And this fact underlies the main criticism of the Treasury's reliance on Threadneedle Street's monetary policy. While low interest rates and QE have kept millions of families afloat, they have failed to produce any growth.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion